Solo Man

| Solo Man | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of Skull XI at the Hall of Human Origins , Washington, D.C.

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †H. e. soloensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| †Homo erectus soloensis Oppenoorth, 1932

| |

| Synonyms[citation needed] | |

| |

Solo Man (Homo erectus soloensis) is a

The Solo Man skull is oval-shaped in top view, with heavy brows, inflated cheekbones, and a prominent bar of bone wrapping around the back. The brain volume was quite large, ranging from 1,013 to 1,251 cubic centimetres (61.8 to 76.3 cu in), compared to an average of 1,270 cm3 (78 cu in) for present-day modern males and 1,130 cm3 (69 cu in) for present-day modern females. One potentially female specimen may have been 158 cm (5 ft 2 in) tall and weighed 51 kg (112 lb); males were probably much bigger than females. Solo Man was in many ways similar to the Java Man (H. e. erectus) that had earlier inhabited Java, but was far less archaic.

Solo Man likely inhabited an open

Research history

Despite what English naturalist

The "apeman of Java" nonetheless stirred up academic interest and, to find more remains, the

From 1931 to 1933, 12 skull pieces (including well-preserved skullcaps), as well as two right tibiae (shinbones), one of which was essentially complete, were recovered under the direction of Oppenoorth, ter Haar, and German-Dutch geologist Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald.[3]: 2–3 Midway through excavation, Oppenoorth retired from the Survey and returned to the Netherlands, replaced by Polish geologist Józef Zwierzycki in 1933. At the same time, because of the Great Depression, the Survey's focus shifted to economically relevant geology, namely petroleum deposits, and the excavation of Ngandong ceased completely. In 1934, ter Haar published important summaries of the Ngandong operations before contracting tuberculosis. He returned to the Netherlands and died two years later. Von Koenigswald, who was hired principally to study Javan mammals, was fired in 1934. After much lobbying by Zwierzycki in the Survey, and after receiving funding from the Carnegie Institution for Science, von Koenigswald regained his position in 1937, but was too preoccupied with the Sangiran site to continue research at Ngandong.[3]: 23–26

In 1935, the Solo Man remains were transported to

The specimens are:[5]: 217

- Skull I, an almost complete skullcap probably belonging to an elderly female;

- Skull II, a frontal bone probably belonging to a three to seven-year-old child;

- Skull III, a warped skullcap probably belonging to an elderly individual;

- Skull IV, a skullcap probably belonging to a middle-aged female;

- Skull V, a probable male skullcap—indicated by its great length of 221 mm (8.7 in);

- Skull VI, an almost complete skullcap probably belonging to an adult female;

- Skull VII, a right parietal bone fragment probably belonging to a young, possibly female, individual;

- Skull VIII, both parietal bones (separated) possibly belonging to a young male;

- Skull IX, a skullcap missing the base probably belonging to an elderly individual (the small size is consistent with a female, but the heaviness is consistent with a male);

- Skull X, a shattered skullcap probably belonging to a robust elderly female;

- Skull XI, a nearly complete skullcap;

- Tibia A, a few fragments of the shaft, measuring 101 mm (4.0 in) in diameter at the mid-shaft, probably belonging to an adult male;

- Tibia B, a nearly complete right tibia measuring 365 mm (14.4 in) in length at 86 mm (3.4 in) in diameter at the mid-shaft, probably belonging to an adult female;

- Ngandong 15, a partial skullcap;[3]: 3

- Ngandong 16, a left parietal fragment;[3]: 3 and

- Ngandong 17, a 4 cm × 6 cm (1.6 in × 2.4 in) left hip joint).[3]: 3

Age and taphonomy

The location of these fossils in the Solo terrace at the time of discovery was poorly documented. Oppenoorth, ter Haar, and von Koenigswald were only on site for 24 days of the 27 months of operation as they needed to oversee other Tertiary sites for the Survey. They left their geological assistants — Samsi and Panudju — to oversee the dig; their records are now lost. The Survey's site map remained unpublished until 2010 (over 75 years later) and is of limited use now, so the taphonomy and geological age of Solo Man have been contentious matters.[3]: 5 All 14 specimens were reported to have been found in the upper section of Layer II (of six layers), which is a 46 cm (18 in)-thick stratum with gravelly sand and volcaniclastic hypersthene andesite. They are thought to have been deposited at around the same time, probably in a now-dry arm of the Solo River, about 20 m (66 ft) above the modern river. The site is about 40 m (130 ft) above sea level.[3]: 15–18

Volcaniclastic rock indicates deposition occurred soon after a

The dating attempts are:

- In 1932, based on the site's height above the present-day river, Oppenoorth suggested Solo Man dated to the Middle/Late Pleistocene transition.[2] Later biochronological studies (using the animal remains to constrain the age) within the next few years by Oppenoorth in 1932, von Koenigswald in 1934, and ter Haar in 1936 agreed with a Late Pleistocene date.[8]

- The Solo Man remains were first radiometrically dated in 1988 and again in 1989, using uranium–thorium dating, to 200 to 30 thousand years ago, a wide error range.[9]

- In 1996, Solo Man teeth were dated, using electron spin resonance dating (ESR) and uranium–thorium isotope-ratio mass spectrometry, to 53.3 to 27 thousand years ago; this would mean Solo Man outlasted continental H. erectus by at minimum 250,000 years and was contemporaneous with modern humans in Southeast Asia,[8] who immigrated roughly 55 to 50 thousand years ago.[10]

- In 2008, gamma spectroscopy on three of the skulls showed they experienced uranium leaching, and the Solo Man remains were re-dated to roughly 70 to 40 thousand years ago. This would still make it possible Solo Man was contemporaneous with modern humans.[9]

- In 2011, argon–argon dating of pumice hornblende yielded a maximum age of 546 ± 12 thousand years ago, and ESR and uranium–thorium dating of a mammal bone just downstream at the Jigar I site a minimum age of 143 to 77 thousand years ago. This extended interval would make it possible Solo Man was contemporaneous with continental H. erectus, long before modern humans dispersed across the continent.[11]

- In 2020, the first comprehensive chronology of the Ngandong site was published which found the Solo River was diverted through the site 500,000 years ago; the Solo terrace was deposited over 316 to 31 thousand years ago; the Ngandong terrace 141 to 92 thousand years ago; and the H. erectus bone bed 117 to 108 thousand years ago. This would mean Solo Man is indeed the last known H. erectus population and did not interact with modern humans.[7]

Classification

The racial classification of

In 1932, Oppenoorth preliminarily drew parallels between the Solo Man skull and that of

Thus, the ancient Java Man, Solo Man, and Rhodesian Man were commonly grouped together in the "Pithecanthropoid-

The claim that Aboriginal Australians were descended from Asian H. erectus was expanded upon in the 1960s and 1970s as some of the oldest known (modern) human fossils were being recovered from Australia, primarily under the direction of Australian anthropologist Alan Thorne. He noted some populations were prominently more robust than others, so he suggested Australia was colonised in two waves ("di-hybrid model"): the first wave being highly robust and descending from nearby H. erectus, and the second wave more gracile (less robust) and descending from anatomically modern East Asians (who, in turn, descended from Chinese H. erectus). It was subsequently discovered that some of the more robust specimens are younger than the gracile ones. In the 1980s, as African species like A. africanus became widely accepted as human ancestors and race became less salient in anthropology, the Out of Africa theory overturned the Out of Asia and multiregional models. The multiregional model was consequently reworked into local populations of archaic humans having interbred and contributed at least some ancestry to modern populations in their respective regions, otherwise known as the assimilation model. Solo Man fits into this by having hybridised with the fully modern ancestors of Australian Aborigines travelling south through Southeast Asia. The assimilation model was not ubiquitously supported. In 2006, Australian palaeoanthropologist Steve Webb speculated instead that Solo Man was the first human species to reach Australia, and more robust modern Australian specimens represent hybrid populations.[12]: 3

The date of 117 to 108 thousand years ago for Solo Man, predating modern human dispersal through Southeast Asia (and eventually into Australia), is at odds with this conclusion. Such an ancient date leaves Solo Man with no living descendants.

Anatomy

The identification as adult or juvenile was based on the closure of the cranial sutures, assuming they closed at a rate similar to modern humans (though they may have closed at earlier ages in H. erectus). Characteristic of H. erectus, the skull is exceedingly thick in Solo Man, ranging from double to triple what would be seen in modern humans. Male and female specimens were distinguished by assuming males were more robust than females, though both males and females are exceptionally robust compared to other Asian H. erectus. The adult skulls average 202 mm × 152 mm (8.0 in × 6.0 in) in length times breadth, and are proportionally similar to that of the Peking Man but have a much larger circumference. Skull V is the longest at 221 mm (8.7 in).[5]: 236–239 For comparison, the dimensions of modern human skulls average 176 mm × 145 mm (6.9 in × 5.7 in) for men and 171 mm × 140 mm (6.7 in × 5.5 in) for women.[18]

The Solo Man remains are characterised by more

At the back of the skull, there is a sharp, thick occipital torus (a projecting bar of bone) which marks a clear separation between the occipital and nuchal planes. The occipital torus projects the most at the part corresponding to the external occipital protuberance in modern humans. The base of the temporal bone is consistent with Java Man and Peking Man rather than Neanderthals and modern humans. Unlike Neanderthals and modern humans, there is a defined bony pyramid structure near the root of the pterygoid bone. The mastoid part of the temporal bone at the base of the skull notably juts out. The occipital condyles (which connect the skull to the spine) are proportionally small compared to the foramen magnum (where the spinal cord passes into the skull). Large, irregular bony projections lie directly behind the occipital condyles.[5]: 246–249

The brain volumes of the six Ngandong specimens for which the metric is calculable range from 1,013 to 1,251 cm3. The Ngawi I skull measures 1,000 cm3; and the three Sambungmacan skulls (respectively) 1,035; 917; and 1,006 cm3. This makes for an average of over 1,000 cm3.[19]: 136 For comparison, present-day modern humans average 1,270 cm3 for males and 1,130 cm3 for females, with a standard deviation of roughly 115 and 100 cm3.[20] Chinese H. erectus (ranging 780 to 250 thousand years ago) average roughly 1,028 cm3, and Javan H. erectus (excluding Ngandong) about 933 cm3. Overall, Asian H. erectus are big-brained, averaging roughly 1,000 cm3.[21] The base of the braincase, and thus the brain, seems to have been flat rather than curved. The sella turcica at the base of the skull, near the pituitary gland, is much larger than that of modern humans, which Weidenreich in 1951 cautiously attributed to an enlarged gland which caused the extraordinary thickening of the bones.[5]: 285

Of the two known tibiae, tibia A is much more robust than Tibia B and is consistent overall with Neanderthal tibiae.[5] Like other H. erectus, the tibiae are thick and heavy. Based on the reconstructed length of 380 mm (15 in), Tibia B may have belonged to a 158 cm (5 ft 2 in) tall, 51 kg (112 lb) individual. Tibia A is assumed to have belonged to a larger individual. Asian H. erectus, for which height estimates are taken (a rather small sample size), typically range from 150–160 cm (4 ft 11 in – 5 ft 3 in), with Indonesian H. erectus in tropical environments typically scoring on the higher end, and continental specimens in colder latitudes on the lower end. The single pelvic fragment from Ngandong has not yet been described formally.[19]: 151–152

Culture

Palaeohabitat

At the species level, the Ngandong fauna is similar overall to the older Kedung Brubus fauna roughly 800 to 700 thousand years ago, a time of mass immigration of large mammal species to Java, including

H. e. soloensis was the last population of a long occupation history of the island of Java by H. erectus, beginning 1.51 to 0.93 million years ago at the Sangiran site, continuing 540 to 430 thousand years ago at the Trinil site, and finally 117 to 108 thousand years ago at Ngandong. If the date is correct for Solo Man, then they would represent a terminal population of H. erectus which sheltered in the last open-habitat refuges of East Asia before the rainforest takeover. Before the immigration of modern humans, Late Pleistocene Southeast Asia was also home to

Judging by the sheer number of specimens deposited at Ngandong at the same time, there may have been a sizeable population of H. e soloensis before the volcanic eruption which resulted in their interment, but population is difficult to approximate with certainty. The Ngandong site was some distance away from the northern coast of the island, but it is unclear where the southern shoreline and the mouth of the Solo River would have been.[3]

Technology

In 1936, while studying photos taken by Dutch archaeologist

Oppenoorth also identified a perfectly round andesite stone ball from Ngandong, a common occurrence in the Solo Valley, ranging in diameter from 67 to 92 mm (2.6 to 3.6 in). As well, similar balls have been identified in contemporaneous and younger European Mousterian and African Middle Stone Age sites, as ancient as African Acheulean sites (notably Olorgesailie, Kenya).[5] On Java, they have been found at Watualang (contemporaneous with Ngandong) and Sangiran.[26] Traditionally, these have been interpreted as bolas (tied together in twos or threes and flung as a hunting weapon), but also individually thrown projectiles, club heads, or plant-processing or bone-breaking tools. In 1993, American archaeologists Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth demonstrated the spherical shape could be reproduced simply if the stone is used as a hammer for an extended period.[27]

In 1938, von Koenigswald returned to the Ngandong site along with archaeologists

Though a strict "Movius Line" is not well supported anymore with the discovery of some hand axe technology in Middle Pleistocene East Asia, handaxes are still conspicuously rare and crude in East Asia compared to western contemporaries. This has been explained as: the Acheulean emerged in Africa after human dispersal through East Asia (but this would require that the two populations remained separated for nearly two million years); East Asia had poorer quality raw materials, namely quartz and quartzite (but some Chinese localities produced handaxes from these materials and East Asia is not completely void of higher-quality minerals); East Asian H. erectus used biodegradable bamboo instead of stone for chopping tools (but this is difficult to test); or East Asia had a lower population density, leaving few tools behind in general (though demography is difficult to approximate in the fossil record).[29]

Possible cannibalism

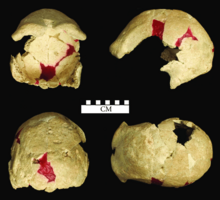

In 1951, Weidenreich and von Koenigswald made note of major injuries in Skulls IV and VI, which they believed were caused by a cutting instrument and a blunt instrument, respectively. They bear evidence of inflammation and healing, so the individuals probably survived the altercation. Weidenreich and von Koenigswald noted that only the skullcaps were found, lacking even the teeth, which is highly unusual. So, they interpreted at least Skulls IV and VI as victims of an "unsuccessful assault", and the other skulls where the base was broken out "the result of more successful attempts to slay the victims," presuming this was done by other humans to access and consume the brain. They were unsure if this was done by a neighbouring H. e. soloensis tribe, or "by more advanced human beings who would have given evidence of their 'superior' culture by slaying their more primitive fellowsman". The latter scenario had already been proposed for the Peking Man (which has similarly conspicuous pathology) by French palaeontologist

Cannibalism and ritual headhunting have also been proposed for the Trinil, Sangiran, and Modjokerto sites (all in Java) based on the conspicuous lack of any remains other than the skullcap. This had been reinforced by the historic practice of headhunting and cannibalism in some modern Indonesian, Australian, and Polynesian groups, which at the time were believed to have descended from these H. erectus populations. In 1972, Jacob alternatively suggested that because the base of the skull is weaker than the skullcap, and since the remains had been transported through a river with large stone and boulders, this was a purely natural phenomenon. As for the lack of the rest of the skeleton, if tiger predation was a factor, tigers usually only leave the head since it has the least amount of meat on it. Further, the Ngandong material, especially Skulls I and IX, were damaged during excavation, cleaning, and preparation.[30]

See also

References

- ^ S2CID 23308894.

- ^ JSTOR 24966028.

- ^ from the original on 2021-10-04. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- .

- ^ from the original on 2021-03-30. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ Huffman, O. F.; de Vos, J.; Balzeau, A.; Berkhout, A. W.; Voight, B. (2010). "Mass death and lahars in the taphonomy of the Ngandong Homo erectus bonebed, and volcanism in the hominin record of eastern Java". Abstracts of the PaleoAnthropology Society 2010 Meetings, PaleoAnthropology: A14. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ S2CID 209410644.

- ^ S2CID 22452375.

- ^ PMID 18479734.

- PMID 30082377.

- PMID 21738710.

- ^ PMID 21350636.

- PMID 21086529.

- JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctvcj2jdw.11.

- ^ S2CID 232323599.

- ^ PMID 18635247.

- (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- .

- ^ PMID 14666536.

- S2CID 21705705.

- PMID 27298467.

- ^ .

- ^ JSTOR j.ctt24hf81.5.

- S2CID 222217295.

- S2CID 4461751.

- ^ S2CID 239106990.

- ISBN 978-0-671-87538-1.

- ^ .

- S2CID 2209392.

- JSTOR 40386169.

External links

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).