Columbia, South Carolina, in the American Civil War

This article may relate to relocate relevant information and remove irrelevant ones. (September 2020) |

Early Civil War history

Columbia became chartered as a city in 1786 and soon grew at a rapid pace, and throughout the 1850s and 1860s it was the largest inland city in the

Columbia's

Camp Sorghum was a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp established in 1864 west of Columbia. It consisted of a 5-acre (20,000 m2) tract of open field, without walls, fences, buildings or any other facilities. A "deadline" was established by laying wood planks 10 feet (3.0 m) inside the camp's boundaries. The rations consisted of cornmeal and sorghum molasses as the main staple in the diet; thus the camp became known as "Camp Sorghum". Due to the lack of security features, escapes were common. Conditions were terrible, with little food, clothing, or medicine, and disease claimed a number of lives among both the prisoners and their guards.[4]

Union capture

Following the

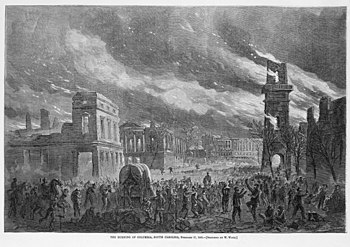

On February 17, 1865, Columbia

Among the buildings burned were the old South Carolina State House and the interior of the incomplete new State House. The Arsenal Academy was also burned; the only surviving building is today the South Carolina Governor's Mansion.

Controversy surrounding the burning of the city began before the war had ended.[7] Shortly afterwards, Southern publications alleged that the burning had been a deliberate Northern atrocity.[8] General Sherman blamed the high winds and retreating Confederate soldiers for firing bales of cotton, which had been stacked in the streets. Sherman denied ordering the burning, though he did order militarily significant structures, such as the Confederate Printing Plant, destroyed.

According to Marion Lucas, author of Sherman and the Burning of Columbia, "the destruction of Columbia was not the result of a single act or events of a single day. Neither was it the work of an individual or a group. Instead it was the culmination of eight days of riots, robbery, pillage, confusion and fires, all of which were the byproducts of war. The event was surrounded by coincidence, misjudgment, and accident. It is impossible, he maintains, to determine with certainty the origin of the fire. The most probable explanation was that it began from the burning cotton on Richardson street. Columbia at this time was a virtual firetrap because of the hundreds of cotton bales in her streets. Some of these had been ignited before Sherman arrived and a high wind spread the flammable substance over the city."[9]

In 2015, The State identified "5 myths about the Burning of Columbia":[10]

- Sherman ordered the burning of Columbia.

- All of Columbia burned.

- There was a "battle" for Columbia.

- Union soldiers burned the Congaree River bridge.

- First Baptist Church was saved by an African-American caretaker.

Reconstruction

During

Notable Civil War personalities from Columbia

- Maxcy Gregg — Confederate brigadier general mortally wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg

- Alexander Cheves Haskell — Colonel of the 1st South Carolina Cavalry, led a Confederate brigade late in the war

William Augustus Reckling (1850–1913) was a noted SC Photographer operating in Columbia 1870–1910 at times with his 2 sons as "Reckling & Sons Photographers" on Senate St now part of the USC campus. The latter has a collection of Reckling's photos of notable South Carolinians of the era as well as a series of stereographs of Columbia.[11]

Civil War tourism

The Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, part of the S.C. Budget and Control Board, showcases an artifact collection from the Colonial period to the space age. The museum houses a collection of South Carolina artifacts from the Confederate period.

The six impacts from Sherman's cannonballs to the granite exterior of the State House were never repaired, and are today marked by bronze stars.

Today, tourists can follow the path General Sherman's army took to enter the city and see structures or remnants of structures that survived the fire. A Civil War walking tour is available.[12]

References

- Magrath, Andrew. "From The Governor of the State, to the People of South Carolina." Legislative System, Messages, 1860–1865. South Carolina Archives, Columbia, South Carolina.

- Simms, William G. Sack and Destruction of the City of Columbia S.C. Columbia: Power Press of Daily Phoenix, 1865. online

- McCarter, James. "The Burning of Columbia, Again." Harper's Magazine 33, October, 1866.

- Whilden, Mary S. Recollections of the War, 1861-1865, 1887. Reprint: Columbia, 1911.

- Gibbes, James Guignard. Who Burnt Columbia? Newberry, SC, 1902

- Hargrett, Lester; JSTOR 40575788. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- Howard, Oliver Otis. Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General, United States Army. New York, 1907

- Snowdon, Yates. Marching With Sherman: A Review of the Letters and Campaign Diaries of Henry Hitchcock. Columbia, 1929

- Burton, Elijah P. Diary of E.P. Burton, Surgeon, Seventh Regiment Illinois, Third Brigade, Second Division, Sixteenth Army Corps, II, 63. Des Moines, 1939

- Miers, Earl Schenck. The General Who Marched To Hell. New York,1951.

- Miers, Earl Schenck. When The World Ended: The Diary of Emma LeConte. New York, 1957

- Lucas, Marion Brunson. Sherman and the Burning of Columbia. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1976

- Fellman, Michael. Citizen Sherman: A Life Of William Tecumseh Sherman. New York, 1995.

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Teal, Harvey S. "Partners with the Sun, South Carolina Photographers, 1840-1940" University of South Carolina Press (2001).

- Campbell, Jacqueline G. "'The Most Diabolical Act of all The Barbarous War': Soldiers, Civilians, and the Burning of Columbia, February, 1865." American Nineteenth Century History, Vol. 3, No. 3, Fall 2002

- Elmore, Tom, "A Carnival of Destruction-Sherman's Invasion of South Carolina." Jogglingboard Press, 2012.

- Elmore, Tom, "Columbia's Civil War Landmarks" The History Press, 2011.

Notes

- ^ U.S. Census 1860

- ^ Lucas, Sherman and the Burning of Columbia.

- ^ Magrath, "From The Governor of the State, to the People of South Carolina."

- ^ Camp Sorghum website

- ^ National Park Service battle description

- ^ Campbell, "'The Most Diabolical Act of all The Barbarous War': Soldiers, Civilians, and the Burning of Columbia, February, 1865."

- ^ Gibbes, Who Burnt Columbia?

- ^ Was the Burning of Columbia, S.C. a War Crime?, New York Times, March 10, 2015

- .

- ^ Wilkinson, Jeff (February 13, 2015). "5 myths about the Burning of Columbia". The State.

- ^ "Partners With the Sun, South Carolina Photographers, 1840-1940." Harvey S. Teal, University of South Carolina Press (2001).

- ^ Columbia tourism Archived 2007-10-16 at the Wayback Machine