Hearne Craton

The Hearne Craton is a

Geological setting

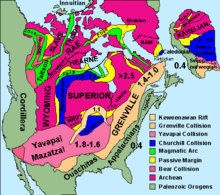

The Hearne Craton is separated from the Rae Craton by the 2,000 km (1,200 mi)-long Snowbird Tectonic Zone (STZ). During the Neoarchaean and Palaeoproterozoic the STZ played a major role when the Western Churchill Province was first assembled and then reworked. The STZ is a record of Neoarchaean plate tectonics similar in scale to modern orogenic belts.[2]

When

Manikewan Ocean

The Manikewan Ocean, a palaeocean named by Stauffer 1984, started to open along the south-east margin of Hearne at 2.075 Ga and had reached a width of 5,000 km (3,100 mi) after a hundred million years. Intra-oceanic arc collision resulted in the Amisk Collage and the Flin Flon – Glennie Complex around 1.92–1.88 Ga.[4] Today these Palaeoproterzoic structures in the Trans-Hudson Orogen welds the Archaean Hearne and the Superior cratons.[5] As the ocean continued to close, an Andean-style arc pluton known as the Wathaman Batholith formed 1.86–1.85 Ga. The subduction of the Manikewan Ocean stopped when the La Ronge Arc collided with Hearne. The final closure of the ocean around 1.83 Ga, when Hearne, Superior, and Sask cratons merged with the Flin Flon – Glennie Complex, was followed by a period of metamorphism that peaked around 1.82–1.8 Ga.[4] The Manikewan Mobile Belt now covers an area of 600,000 km2 (230,000 sq mi) but is overlain by Middle Proterozoic Athabasca sandstone.[6]

References

Notes

- ^ Clowes, Cook & Ludden 1998, p. 2

- ^ Jones et al. 1993, Abstract; Introduction, p. 1

- ^ Aspler, Chiarenzelli & McNicoll 2002, Introduction, pp. 332–335

- ^ a b Maxeiner & Rayner 2011, Introduction, pp. 93–95

- ^ Stern et al. 2000, Introduction, p. 1808

- ^ Stauffer 1984, Abstract

Sources

- Aspler, L. B.; Chiarenzelli, J. R.; McNicoll, V. J. (2002). "Paleoproterozoic basement-cover infolding and thick-skinned thrusting in Hearne domain, Nunavut, Canada: intracratonic response to Trans-Hudson orogen". Precambrian Research. 116 (3): 331–354. . Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Clowes, R. M.; Cook, F. A.; Ludden, J. N. (1998). "Lithoprobe leads to new perspectives on continental evolution" (PDF). GSA Today. 8 (10): 1–7. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Jones, A. G.; Craven, J. A.; McNeice, G. W.; Ferguson, I. J.; Boyce, T.; Farquarson, C.; Ellis, R. G. (1993). "North American Central Plains conductivity anomaly within the Trans-hudson orogen in northern Saskatchewan, Canada" (PDF). Geology. 21 (11): 1027–1030. . Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Maxeiner, R. O.; Rayner, N. (2011). "Continental arc magmatism along the southeast Hearne Craton margin in Saskatchewan, Canada: comparison of the 1.92–1.91 Ga Porter Bay Complex and the 1.86–1.85 Ga Wathaman Batholith". Precambrian Research. 184 (1): 93–120. . Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Stauffer, M. R. (1984). "Manikewan: An early proterozoic ocean in central Canada, its igneous history and orogenic closure" (PDF). Precambrian Research. 25 (1): 257–281. . Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Stern, R. A.; Machado, N.; Syme, E. C.; Lucas, S. B.; David, J. (2000). "Chronology of crustal growth and recycling in the Paleoproterozoic Amisk collage (Flin Flon Belt), Trans-Hudson orogen, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 36 (11): 1807–1827. . Retrieved 31 May 2016.