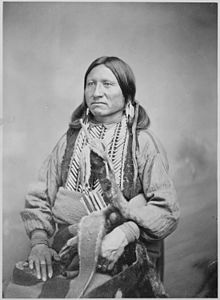

Kicking Bird

Kicking Bird | |

|---|---|

Chief Kicking Bird | |

| Born | c. 1835 Possibly Oklahoma |

| Died | May 3, 1875 (aged 39–40) Fort Sill, Oklahoma |

| Nationality | Kiowa |

| Other names | The Kicking Bird Eagle Who Strikes with his Talons Striking Eagle |

| Known for | A Chief of the Kiowa Nation, warrior, peacemaker |

| Relatives | Stumbling Bear (father) Son of the Sun (brother) Big Arrow (brother) Coquit (brother) |

Kicking Bird, also known as Tene-angop'te, "The Kicking Bird", "Eagle Who Strikes with his Talons", or "Striking Eagle" (c. 1835 - May 3, 1875) was a High Chief of the

Though he was a great warrior who participated in and led many battles and raids during the 1860s and 1870s, he is mostly known as an advocate for peace and education among his people. He enjoyed close relationships with whites, most notably the Quaker teacher Thomas Battey and

Early life (1835–65)

At the time of Kicking Bird's birth in about 1835, the Kiowas inhabited the Texas Panhandle, western Oklahoma, and southwestern Kansas.[1] Not much is known of his early life, but he participated in the Kiowa warrior tradition and was a renowned warrior and hunter. His early success qualified him as an "onde," or Kiowa warrior supreme, granting him first-rank social status in his tribe.[2] In addition to an outstanding war-record, to be an "onde" required that a man be wealthy, generous, aristocratic in demeanor, and an imposing presence on horseback – all qualities possessed by Kicking Bird.[3]

He fought against the

As Kicking Bird matured, he recognized the futility of the raiding that dominated

A series of clashes between the

The

Later life (1865–75)

Political involvement

After

Kicking Bird's first actions as sub-chief were for peace, but he was primarily concerned with the annuity situation. When the Kiowa had moved onto the reservations, they had been promised annuity payments for buying food and supplies; however, the annuities were not always paid as promised, and were being handled by a corrupt agent who hampered the promised flow of goods.

Indian-white friction resurfaced following the

Obstacles to peace and prestige

As a result of the

In response to the lack of annuities and tribal land, the Kiowa and their contemporaries resorted to looting and plundering throughout the Plains, which undermined Kicking Bird's efforts towards peace. On January 15, 1870, a body of Kiowas under Satanta intercepted a Texas herd driven by Jacob Hershfield and robbed the drovers of money and supplies before killing some 150-200 head of cattle. Kicking Bird arrived on the scene and defused the situation. Hershfield accounted that had it not been for Kicking Bird, he and his men would have died.[3]

Kicking Bird received intense criticism for his close relationships with white people and his renunciation of hunting and advocation of farming. The ranks of warring chiefs Satanta and Guipago swelled in comparison and Kicking Bird lost much tribal support. When the Kiowas hosted a sun dance to celebrate the Summer Moon of 1870, many warriors talked of staying out on the Plains instead of living on reservations with inadequate annuities. Kicking Bird spoke strongly against this and urged that the tribes cultivate friendly relations with the whites and continue to live on reservations. Though a chief, Kicking Bird received much scorn during the sun dance from young Kiowas, and the lack of respect was evident. They said "he had been a great warrior before the white men penned him up on the reservation. Now he talked like a woman."[4]

Battle of Little Wichita River

Responding to claims that he was a coward and had become effeminate, Kicking Bird assembled a war party and invited some of his chief critics and worst tormentors to participate -

In July 1870, his war party, some 100 strong, crossed the

The Battle of Little Wichita River reaffirmed Kicking Bird's martial acumen and also reinforced his status as Kiowa chief. His victory marked the end of his military career and he expressed regret that tribal divisions forced his hand in the battle. He would spend the rest of his life cultivating peace with whites.

The schism between peace-minded and war-minded Kiowa leaders was exacerbated by the increased presence of the U.S. military and Quakers by the end of 1870. Kicking Bird was clearly the foremost advocate for an accommodation with the United States, but was opposed by

Warren Wagontrain Raid

In 1871, a ten-wagon mule train moving through Texas was attacked by some 100 Kiowa and Comanche warriors under the direction of

Efforts towards conciliation, 1871–73

Over the next two years Kicking Bird worked to obtain the release of

Kicking Bird engaged in numerous activities to placate Texas governor

During a June 1873 sun dance, Kicking Bird personally prevented a major Indian outbreak. Discouraged about Satanta and Big Tree's imprisonment, many chiefs clamored for a multitribal assault on the outside forces. Kicking Bird spoke against military action and urged patience. The excitement abated, and the chiefs agreed to wait. This meeting was maybe the closest the Plains tribes would ever come to a multi-tribal assault.

Finally, on October 7, 1873, Satanta and Big Tree were released, a result of Guipago's straightforward explanation to Indian agent James Haworth that the patience of his Kiowa warriors, as well as his own, was wearing thin after the Kiowa had lived up to their promises by remaining peaceful in the summer of 1873.[3] According to his apologists, Kicking Bird's skillful negotiation in the release of Satanta and Big Tree earned him the loyalty of nearly two-thirds of his tribesmen.[2]

Head chief

Kicking Bird's adeptness as a peace leader could not prevent his tribe's immense dissatisfaction with conditions on the reservations, and, in late 1873, the Kiowa once again took the warpath. In the midst of the fighting,

Kicking Bird was successful in keeping his followers on the reservation, but Guipago's scorn towards the "road of peace" and attitude towards that of war severely undermined Kicking Bird's efforts at pacification.[3] On June 27, 1874, a consolidated force of warriors launched an attack that would become known as the Second Battle of Adobe Walls.[2] Guipago and Satanta were among the Kiowas participating in the skirmish. Following the battle, Kicking Bird and Satanta were in favor of making peace, but Guipago and several other chiefs refused and advocated war against the whites. Kicking Bird worked earnestly to keep his people unified and avoid conflict, but both of his goals proved elusive.

In response to the increase of Indian raids throughout the Plains, the United States War Department overrode the Quaker Indian peace policy and issued orders to separate the Kiowas into two groups of friendly and unfriendly Kiowa. True to his word, Kicking Bird led three-fourths of the Kiowa back to their reservation at Fort Sill, which had become a city of refuge for his people. Meanwhile, Indian hostilities continued and Kicking Bird actively sought to pacify the raiding Kiowas and protect them from punishment. He succeeded in bringing six chiefs and 77 tribespeople, who surrendered their arms, to the reservation. Meanwhile, the hostile chiefs led the remainder of the Kiowa westward with the objective of reaching safe haven at Palo Duro Canyon, while the U.S. Army followed at their heels.[3]

When

As chief and the principal intermediary between federal authorities and his tribe, Kicking Bird was put in charge of the Kiowa captured in the 1874-1875 uprising. When it was decided that some of the hostile Kiowa would be sent to Florida for incarceration at

Education

Kicking Bird was the foremost Kiowa advocate for education and enjoyed a close relationship with Quaker teacher Thomas C. Battey. Kicking Bird and Battey first met on February 18, 1872, and in later meetings Kicking Bird requested that Battey, or Thomissey as he was known, teach his daughter Topen and live among the Kiowa.[3] Battey was understandably fearful of the Kiowa, but was reassured in numerous meetings with Kiowa leaders that the Quaker would be greeted with friendship and peace.

After waiting for tensions to settle among the Kiowa, Kicking Bird agreed to take Battey back with him to his camp. Kicking Bird's brother Ze'bile invited Battey to share his lodge and Battey soon began teaching. The first Kiowa classes opened on January 23, 1873, and were hampered by a language barrier and intrusive and curious onlookers.[3] Early on, Battey faced some opposition but was protected by Kicking Bird and other chiefs. Kicking Bird's interest in schooling for the Kiowa children was paramount in bringing education to his tribe but in the context of the assimilation policy, not all Kiowa welcomed white education.

With many influential Kiowa following the path of formal education for Kiowa children set by Kicking Bird and Battey, the first school for the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache children of Fort Sill post was established. The school opened on February 27, 1875, and Agent Haworth appointed two chiefs from each of the tribes to serve as a board of education. Forty-four Kiowa and Comanche children were soon enrolled.[3]

Mysterious death and family

On May 3, 1875, while at

The most popular story maintains that Kicking Bird was poisoned by a vindictive tribesman. It was widely assumed that, with his death occurring relatively soon after the departure of the Fort Marion prisoners, an angry Kiowa or a white who stood to gain from the chief's death slipped poison into his coffee. One account holds that Kicking Bird may have been poisoned by one of his wives for having delivered her brother to Fort Marion.[3]

Another story maintains that the medicine man Maman-ti placed a hex of death on Kicking Bird for his role in naming prisoners to be sent to Fort Marion, himself included. Most contemporary Kiowas accepted this legend, though it too proves inconclusive. Had Maman-ti's hex of death been successful, he would have perished three days after Kicking Bird. Instead, his death came on July 29, 1875 (three months after Kicking Bird's), and may have been the result of the close confinement within the walls of the old Spanish Fort.

Still another account of Kicking Bird's death maintains that something may have been wrong with his heart that caused his death. Agent Haworth noted that the night before his death, Kicking Bird had been up late and told someone that "his heart felt just like someone had hold of it pulling it out."[3] The next morning, as was custom for almost all diseases, Kicking Bird went to the creek and came back after he felt better. Shortly after coming out of the water and having a cup of coffee, Kicking Bird died. This version fits descriptions in modern medical science of someone having a heart attack, but is not conclusive.

Kicking Bird had a daughter, Topen, as well as five other children, with his first wife, who died in 1872. After he remarried in 1874, he had a son Little John, who was ten months old when Kicking Bird died.

His known brothers were Pai-Talyi' (Son-of-the-Sun, or Sun Boy), Ze'bile (Big Arrow), and Coquit. His father was Andrew Stumbling Bear.[3]

See also

References

- ^ May, Jon D. "Kicking Bird (ca. 1835-1875)". Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Archived from the original on 2011-09-05. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hosmer, Brian C. "Kicking Bird". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Hoig, Stan and Wilbur S. Nye (2000). The Kiowas & the Legend of Kicking Bird. Niwot: University of Colorado.

- ^ Brown, 248.

- ^ Brown, 249.

- ^ Hamilton.

- ^ Schnell, 168.

Bibliography

- Brown, Dee Alexander. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York: Bantam, 1972.

- Hamilton, Allen Lee. "WARREN WAGONTRAIN RAID." Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/btw03

- Hoig, Stan, and Wilbur S. Nye. The Kiowas & the Legend of Kicking Bird. Niwot: University of Colorado, 2000.

- Hosmer, Brian C."KICKING BIRD." Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fki03

- May, Jon D. "KICKING BIRD (ca. 1835-1875)." KICKING BIRD (ca. 1835-1875). Oklahoma Historical Society, 2007. Web. 17 Mar. 2013. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/K/KI006.html Archived 2011-09-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Meadows, William C. Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche Military Societies: Enduring Veterans, 1800 to the Present. Austin: University of Texas, 1999.

- Schnell, Steven M. "The Kiowa Homeland in Oklahoma." Geographical Review 90.2 (2000): 155–76. JSTOR. Web. 19 Mar. 2013.