Leo Martello

Leo Martello | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 26, 1930 Dudley, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | June 29, 2000 (aged 69) |

| Occupations |

|

Leo Martello (September 26, 1930 – June 29, 2000) was an American

Born to a working-class

After the

Early life

Youth: 1930–49

Martello was born on September 26, 1930, in

"It is extremely doubtful that there ever was a Sicilian tradition of Wicca that had been passed down through the [Martello] family, yet it is possible that Martello's cousins had created their own Wiccan coven, or that they had instead been members of a folk magical tradition which Martello then embellished. Equally, the entire scenario could be fiction."

— Pagan studies scholar Ethan Doyle White, 2016.[3]

Martello later claimed to have experienced

Martello never produced any proof to support his claims, and there is no independent evidence that corroborate them.[6] An anonymous woman who had known Martello informed the researcher Michael G. Lloyd that during the 1980s, he had told her that he had never been initiated into a tradition of Witchcraft, and that he had simply embraced occultism in the 1960s in order to earn a living.[6] The Pagan studies scholar Ethan Doyle White expressed criticism of Martello's claims, noting that it was "extremely doubtful" that a tradition of Wicca could have been passed down through Martello's Sicilian family. Instead, he suggested that Martello might have been instructed in a tradition of folk magic that he later embellished into a form of Wicca, that the cousins themselves had constructed a form of Wicca that they passed on to Martello, or that the entire scenario had been a fabrication of Martello's.[3]

New York City: 1950–68

Based in New York City, in 1950 Martello founded the American Hypnotism Academy, continuing to direct the organization until 1954.[4] From 1955 to 1957, he served as treasurer of the American Graphological Society, and worked as a freelance graphologist for such corporate clients as the Unifonic Corporation of America and the Associated Special Investigators International.[7] He also published a column titled "Your Handwriting Tells" for eight years that ran in the Chelsea Clinton News, and supplied various articles on the subject of graphology to different magazines.[8] In the city, he also began to frequent the gay scene.[8] In 1955, Martello was awarded a Doctorate in Divinity by a non-accredited organization, the National Congress of Spiritual Consultants, a clearing house for registered yet unaffiliated ministers.[7] That year, he founded the Temple of Spiritual Guidance, taking on the role of Pastor, which he would continue in until 1960, when he began to focus on his writing and his new philosophy of "psychoselfism".[7] In 1961 he published his first book, Your Pen Personality, in which he discussed the manner in which handwriting could be used to reveal the personality of the writer.[8] Martello corresponded with California-based Pagan Victor Henry Anderson, and it was at Martello's encouragement that Anderson established his Mahaelani Coven circa 1960.[9]

Martello claimed that in the summer of 1964, he moved to

Public activism

Gay Liberation: 1969–70

In July 1969, Martello attended an open meeting of the

The GLF was structured around a system of anarchic consensus, which made it difficult for the group to reach conclusions on any issue, and heated arguments became commonplace at its meetings.

WICA and WADL: 1970–74

In 1970, Martello founded the Witches International Craft Associates (WICA), through which he issued The WICA Newsletter, set up to explain what Witchcraft and Wicca was to the wider public and to serve as a resource through which occultists could contact one another.

"Where do I begin to write about a legend? A man who gave tirelessly of himself for the fight for human rights, animal rights, gay and lesbian rights, and for Witches worldwide to worship in complete freedom? Leo Martello was an amazingly compassionate man. He never turned away anyone who genuinely needed his time and effort in the pursuit of a just cause. He fought long and hard for the freedom of Witches and Pagans."

— Lori Bruno, Martello's friend and co-founder of the Trinacrian Rose Coven, 2002.[21]

Inspired by his victory over the Parks Department, Martello founded an organization devoted to campaigning for the religious rights of Witches, the Witches Anti-Defamation League (WADL), which would eventually be renamed the Alternative Religions Education Network (AREN).[22] For WADL, he authored an essay titled "The Witch Manifesto", likely influenced by Carl Wittman's "Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto" (1970), which demanded that the Roman Catholic Church face a tribunal for crimes committed against accused witches in the Early Modern period and that they pay reparations to the modern Witchcraft community for those actions.[23] During this decade he authored a column for Gnostica magazine which was titled "Wicca Basket", a pun on the phonetic similarity between "Wicca" and "wicker".[24]

In 1971, a young gay Wiccan named

In November 1972, Martello lectured at the first Friends of the Craft conference, held at New York's First Unitarian Church.[32] In April 1973, he moved to England for six months, where he was initiated and trained in the three degrees of Gardnerian Wicca by the Sheffield coven run by Patricia Crowther and her husband Arnold Crowther.[33] He continued to encourage acceptance of homosexuality within the Pagan and Witchcraft community, authoring an article titled "The Gay Pagan" for Green Egg magazine.[34] He expressed the view that homophobic Wiccans were "sexually insecure" and that they viewed the religion simply as "a ritual means of fornication".[35] He was also among the prominent male Pagans to endorse feminist and female-only variants of Wicca, such as the Dianic Wicca promoted by Zsuzsanna Budapest.[36]

Later life

During the 1990s, Martello retired from his public work.[37] Doyle White noted that while Martello faded from prominence as the head of the Strega Wicca movement, the tradition gained a "new public advocate" in Raven Grimassi.[3] Martello died of cancer on June 29, 2000.[38] Bruno was the executrix of his estate.[37]

Personal life

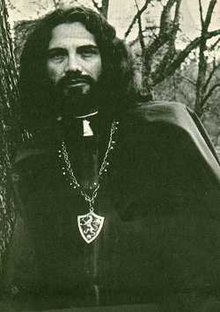

Lloyd described Martello as "a lanky, hungry scrapper with piercing eyes, the face of a dark angel, and a mouth like a bear trap",[39] while in her encyclopaedia on Wicca, Rosemary Ellen Guiley described him as "a colourful figure, known for his humor".[40] Bruno described him as "a loving man, yet sometimes caustic", stating that to know him "was an honor, and ever a challenge".[21] He was often noted for his scruffy appearance, with him typically wearing second-hand clothes.[41]

Beliefs

Martello defended the growing rise of feminists in Wicca during the 1970s, criticizing what he deemed to be the continual repression of women within the Pagan movement.[42] He also espoused the view that any Pagan who was involved in the U.S. government or military was a hypocrite.[43] He was critical of Wiccans who espoused a division between white magic and black magic, commenting that it had racial overtones and that many of those advocating such a view were racist.[44]

Although aware that historians had criticized the witch-cult hypothesis of Margaret Murray, Martello stood by her claims, believing that the cult had been passed through oral tradition and thus evaded appearing in the textual sources studied by historians.[45]

Martello thought it unimportant that many Wiccans had lied about the origins of their beliefs, being quoted by Pagan journalist Margot Adler in her book Drawing Down the Moon as having stated

Let's assume that many people lied about their lineage. Let's further assume that there are no covens on the current scene that have any historical basis. The fact remains: they do exist now. And they can claim a spiritual lineage going back thousands of years. All of our pre-Judeo-Christian or Moslem ancestors were Pagans![46]

Publications

| Year of publication | Title | Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Your Pen Personality | Self-published |

| 1964 | It's in the Cards: The Atomic-Age Approach to Card Reading Using Psychological and Parapsychological Principles | Key Publications |

| 1966 | It's in the Stars: A Sensible Approach to and a Psychological Evaluation of Astrology in this "Age of Enlightenment" | Key Publications |

| 1966 | How to Prevent Psychic Blackmail: The Philosophy of Psychoselfism | S. Weiser |

| 1969 | Weird Ways of Witchcraft | HC Publishers |

| 1969 | Hidden World of Hypnotism: How to Hypnotize | HC Publishers |

| 1971 | Curses in Verses: Spelltime in Rhyme | Hero Press |

| 1972 | Black Magic, Satanism, Voodoo | Castle Books |

| 1972 | Understanding the Tarot | Castle Books |

| 1973 | Witchcraft: The Old Religion | University Books |

| 1990 | Reading the Tarot: Understanding the Cards of Destiny | Perigee Trade |

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 64.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c d Doyle White 2016, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 65.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 65; Doyle White 2016, p. 50.

- ^ a b Lloyd 2012, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e Lloyd 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225; Lloyd 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 68–69; Doyle White 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Lloyd 2012, p. 75.

- ^ a b Lloyd 2012, p. 76.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, p. 79; Doyle White 2016, p. 51.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 136; Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, pp. 80–82; Doyle White 2016, p. 51.

- ^ a b Bruno n.d.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 136; Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Clifton 2006, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 87.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 95.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 127.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 128.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 229.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 193.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 114.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 60.

- ^ a b Guiley 2008, p. 226.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 226; Lloyd 2012, p. 554; Bruno n.d..

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 64.

- ^ Guiley 2008, p. 225.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 228.

- ^ Adler 2006, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 388.

- ^ Lloyd 2012, p. 192; Doyle White 2016, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Adler 2006, p. 85.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-14-303819-1.

- Bruno, Lori (n.d.). "Dr. Leo Louis Martello - A Memorial". Our Lord and Lady of the Trinacrian Rose. Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-0202-6.

- Doyle White, Ethan (2016). Wicca: History, Belief, and Community in Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Brighton, Chicago, and Toronto: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-754-4.

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (2008). The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca (third ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816071043.

- Lloyd, Michael G. (2012). Bull of Heaven: The Mythic Life of Eddie Buczynski and the Rise of the New York Pagan. Hubbarston, MAS.: Asphodel Press. ISBN 978-1938197048.