Monarchian Prologues

The Monarchian Prologues are a set of

Priscillianist compositions from the late fourth or early fifth century.[1] They appear to be the work of a single author.[2] John Chapman even concluded that they were the work of Priscillian himself, who died in 386.[3]

The Latin style of the prologues is convoluted and difficult to understand. The prologues provide background on the traditional authors (

Luke and John) and their theological purposes.[1][2] Since Luke and John were also credited with the Acts of the Apostles and the Book of Revelation, respectively, information contained in their prologues was eventually spun out into separate prologues to Acts and Revelation. The earliest manuscript with these separate prologues is the Codex Fuldensis of 541–546.[4]

The author was working with the

Griesbach hypothesis.[2] Nevertheless, the prologues were often copied into Vulgate manuscripts with the now current order of the gospels.[1] They are in fact a standard feature in the earliest Vulgate manuscripts.[5]

The prologues are, however, of no value as a historical source for the evangelists' backgrounds. They rely on the biblical text itself and various unreliable traditions as sources.

Chapman printed the Latin text with translations and commentary, acknowledging that they were "masterpieces of the art of concealing one's meaning and of not basely betraying it to the scorner". (first words) of the four prologues, by which they are commonly identified are:

- Mattheus ex Iudaeis[16] ('Matthew, who was of the Jews')[12]

- Hic est Iohannes euangelista unus[17] ('This is John the evangelist, one')[18]

- Lucas Syrus natione Antiochensis[19] ('Luke, a Syrian of Antioch by nation')[14]

- Marcus euangelista dei[20] ('Mark, the evangelist of God')[21]

Gallery

-

The beginning of the prologue to Matthew in the Codex Amiatinus

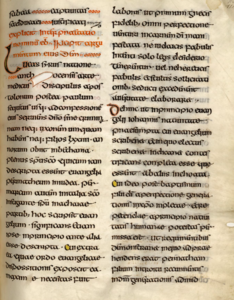

-

The beginning of the prologue to Luke in the Echternach Gospels

-

The beginning of the prologue to John in theEgerton Gospels

-

The beginning of the prologue to Acts in the Codex Fuldensis

-

The beginning of the prologue to Revelation in the La Cava Bible

Notes

- ^ a b c Edwards 2022.

- ^ a b c d Orchard & Riley 1987, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 253.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 254.

- ^ a b c Chapman 1908, p. 277.

- ^ Chapman 1908, pp. 271–275.

- ^ Heard 1955, p. 3.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 226.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 285.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 288.

- ^ Chapman 1908, pp. 217–236 (quotation at p. 223).

- ^ a b Chapman 1908, p. 225.

- ^ Chapman 1908, pp. 227–228.

- ^ a b Chapman 1908, p. 231.

- ^ Chapman 1908, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 217.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 218.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 228.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 220.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 221.

- ^ Chapman 1908, p. 235.

Bibliography

- Chapman, John (1908). Notes on the Early History of the Vulgate Gospels. Clarendon Press.

- Edwards, Mark (2022). "Monarchian Prologues". In Andrew Louth (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Heard, R. G. (1955). "The Old Gospel Prologues". The Journal of Theological Studies. 6 (1): 1–16. .

- Orchard, Bernard; Riley, Harold (1987). The Order of the Synoptics: Why Three Synoptic Gospels?. Mercer University Press.