Reichstag inquiry into guilt for World War I

The Reichstag inquiry into guilt for World War I

Its four subcommittees were assigned to examine the causes for the outbreak of the war; what opportunities for peace had presented themselves during the war and why they had failed; acts by Germany that were contrary to international law; and the causes for Germany's defeat. During its thirteen-year life (1919–1932), the committee suffered under increasing interference from the government, which wanted to prevent a German admission of guilt before the world public. The committee also encountered passive resistance from the civil service and military. In many cases, it bowed to pressure and did not take decisive action to require their cooperation. The majority of Germans also shifted more and more to the side of the political forces that had no interest in a public clarification. The results of the individual subcommittees were thus of limited value.

The work itself, as far as the records show, was mostly done prudently and conscientiously. The files containing the course of the proceedings and the expert opinions are accordingly of high value as source material. The investigative committee was not re-established after the Nazi Party won the largest number of seats in the July 1932 Reichstag election. Some of its work remained incomplete and much that had been finished was either suppressed or was destroyed during World War II.

Background

In the immediate aftermath of the

On 12 March 1919, Justice Minister Otto Landsberg of the SPD submitted a bill for the establishment of a criminal court to the Weimar National Assembly, the interim parliament also charged with writing a new constitution for Germany. Although Ludendorff, retired General Erich von Falkenhayn and others had called for such a court, the conservative parties in the National Assembly spoke out against it. The governing Weimar Coalition made up of the SPD, the Catholic Centre Party and the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP) also felt pushed into a more defensive role and in the end no longer considered the approach opportune. It was argued that it was more important to establish the facts than to prosecute, and that sound public opinion would then "weed out the reactionary lie".[3] In November 1918, the new revolutionary leaders, especially those of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) – a more leftist and strongly anti-war breakaway from the originally united SPD – had sought to place the blame for the war on the German side in order to demonstrate to Germany and the world that they had broken completely with militarism. As time went on, however, the leaders of the Majority Social Democrats (MSPD) saw primarily the disadvantages of such a viewpoint for the upcoming peace negotiations.[4]

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919, changed the discussion by establishing the so-called war guilt article as the basis for the reparations that the treaty imposed. Without using the word "guilt", Article 231 stated:

The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.[5]

In an attempt to evade the burdens and challenge the treaty, the German government portrayed the article as factually incorrect. It led to "state promotion and high-level institutionalization"[6] of propaganda regarding Germany's responsibility for the war and also for the possibility of a revision of the treaty. The Foreign Office founded and financed the Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War and the Working Committee of German Associations, a group of 2,000 organizations that included the Catholic Caritas Internationalis, the Association of German Cities (Deutscher Städtetag) and the Working Committee of Patriotic Associations. A national consensus emerged against any kind of German admission of guilt.

The original focus on the war and its perpetrators expanded to include the question of responsibility for Germany's defeat. Instead of assigning a state court to clarify the question, a resolution to establish a committee was passed on 20 August 1919 at the 84th session of the Weimar National Assembly that had adopted the new Weimar Constitution just nine days previously. The procedures of the committee of inquiry were not governed by the Rules of Procedure of the Reichstag but by the Work Plan for Committees of Inquiry of 16 October 1919.[7]

In the resolution of the National Assembly, the committee was given the task "to determine, by gathering all evidence:

- what events led to the outbreak of the war, caused its prolongation and brought about its loss, in particular:

- what opportunities presented themselves in the course of the war for arriving at peace discussions and whether such opportunities were handled without due diligence;

- whether fidelity and good faith were observed in the communication among the political agencies of the Reich leadership, between the political and the military leadership, and with the people's representatives or their confidants;

- whether in the military and economic conduct of the war, measures were ordered or tolerated which violated provisions of international law or were cruel and harsh beyond military and economic necessity."[8][9]

The investigating committee was constituted one day later, on 21 August 1919. It had the right to summon any German for questioning and to inspect all official files. Those summoned were usually referred to as respondents; they stood somewhere between defendants and witnesses. No defense attorneys were appointed.[10] The procedure in the investigative committee was to be similar to that of the criminal trial.[3]

The first chairman was the Hamburg senator Carl Wilhelm Petersen of the center-left German Democratic Party (DDP), later Walther Schücking, also DDP, and in the final phase Johannes Bell of the conservative Catholic Centre Party. Ludwig Herz was initially appointed managing director but was replaced shortly thereafter by Eugen Fischer-Baling, also for a time a member of the DDP.

The committee was staffed according to the distribution of seats in the National Assembly and then, after it was constituted in June 1920, the Weimar Reichstag. The members and their staffs therefore changed in the individual election periods.[11]

Tasks and structure

On 14 October 1919, Chairman Carl Petersen presented to parliament the goals, a preliminary outline of material and an associated work plan as the initial result of the investigative committee's deliberations.[12] The emphasis was on the questions that had been the subject of controversy in Germany since the fall of 1918:[13]

- clarification of the events that led to the outbreak of war in July 1914 as a result of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary;

- clarification of all possibilities for peace talks and of the reasons which caused such possibilities to fail, or plans and decisions to that effect on the part of Germany or, if talks did take place, for what reasons such talks were unsuccessful;

- clarification of acts of war which were prohibited by international law or, if not prohibited by international law, were nevertheless disproportionately cruel or harsh;

- clarification of economic war measures in the occupied territories which were illegal under international law or whose implementation, without promising any particular military advantage, entailed a hardship unjustifiable for the population concerned and for their country.

Interestingly, the issue of blame for Germany's defeat in the war, which was part of the original parliamentary resolution, did not appear in Petersen's proposal, although shortly after work began, the fourth subcommittee took over the issue, while the third handled all questions of international law.

Four subcommittees, each with six to eight members, were formed to carry out the work.[14] The chairmanship of the committee as a whole and of the subcommittees was assigned to the various parties in accordance with a distribution formula decided in the Reichstag's Council of Elders.[15] The chairmanship of the full committee was held by the German Democratic Party (DDP). The first subcommittee was chaired by the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the second by the DDP, SPD, ant the liberal German People's Party (DVP), the third by the Centre Party and the fourth primarily by the nationalist conservative German National People's Party (DNVP).

Difficulties in the work of the subcommittees

An office with four academically educated secretaries was established under the committee's Secretary General, Eugen Fischer-Baling. The secretaries, who had been civil servants trained under the Empire, gained considerable influence over the investigations they supervised. They selected literature and experts, worked out methods of investigation, prepared the examination of witnesses and oversaw the procurement and utilization of files.[16] Their rights made them equal to the committee members, and they could make a pre-selection of the files, delay their release or classify them as secret material and thus prevent their publication by the committee.[17]

The ministries provided the committee with civil servants and military officers to help the parliamentarians navigate the archives and provide background information. Over time the ministerial assistance evolved into censorship points that stopped the publication of unpleasant details. Historian Ulrich Heinemann concluded that "even before the investigations had begun, the committee was confronted with serious written statements and concerns from the executive branch" which intensified as work progressed.[16]

Testimony of Hindenburg and Ludendorff

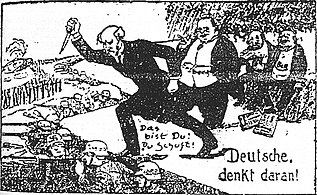

The impact of the mixture of revisionist propaganda, sometimes inadequate preparation of witnesses, questioning by the secretaries, censored or obstructed inspection of files, etc., became apparent at the first public subcommittee meetings which began on 21 October 1919 with a strong presence of the national and international press. It was a session of the second subcommittee which was to clarify the failed peace options and was chaired by Fritz Warmuth of the German National People's Party. One of the invitees was former Vice Chancellor Karl Helfferich (DNVP) who was allowed the opportunity to allege that republicans were the real culprits behind Germany's defeat in the war. In November 1919 Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff appeared before the committee. Hindenburg in particular was received servilely.

He refused to take the oath until Ludendorff was permitted to read a statement saying that they were under no obligation to testify since their answers might expose them to criminal prosecution, but they were waiving their right of refusal. On the stand Hindenburg read through a prepared statement, ignoring the chairman's repeated demands that he answer questions. He testified that the German Army had been on the verge of winning the war in the autumn of 1918 and that the defeat had been precipitated by unpatriotic politicians and disloyal elements on the home front. He brought up a dinner conversation that Ludendorff had had with Sir Neill Malcolm, who was Chief of Staff for the British Fifth Army in the First World War. In response to a wordy tirade from Ludendorff about the army's betrayal, Malcolm had reportedly asked him:

"Do you mean, General, that you were stabbed in the back?" Ludendorff's eyes lit up and he leapt upon the phrase like a dog on a bone. "Stabbed in the back?" he repeated. "Yes, that's it, exactly, we were stabbed in the back."[18]

When Hindenburg finished reading the statement, he walked out of the hearings despite being threatened with contempt. Heinemann called his appearance a high-profile inauguration of the stab-in-the-back myth.[19]

Referring to the DNVP committee chairman, Eugen Fischer-Baling commented that a worse error than the appointment of an opponent of the revolution as the first spokesman of the revolutionary quasi-tribunal could not be imagined.[20] As a result of the Helfferich-led sessions, the committees stopped meeting in public and attracted less and less attention from the German people.

Investigations and results

It was to be expected that those in the Empire who had held responsibility would try to cover up and deny their mistakes. The committee therefore also tried to let their opponents from the imperial era have a say and to assess controversial statements on the basis of the files, often supported by expert opinions.

While the published results of the inquiries were sometimes the result of dubious compromises among the committee's members, the investigations, expert opinions and disputes in the subcommittees brought important findings to light. There has not as yet been a comprehensive analysis of them.

First subcommittee: outbreak of war

The first subcommittee initially turned to the immediate background of the war but soon decided to include its wider background as well, focusing on the broad policy lines of the great powers from 1870 onward.[21] The ambitious goal of presenting the "first authoritative work on the background of the war from the German side"[21] could not, however, be met, in particular the question of whether Germany and the other Central Powers had forced the war on the Allies.

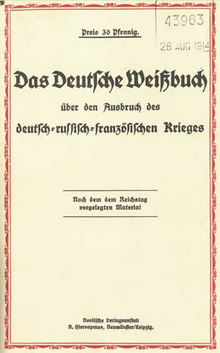

Above all it was "the ongoing intervention of the Foreign Office"[22] that delayed the committee's work so substantially. The Office prevented the publication of four reports by renowned experts, including the legal historian Hermann Kantorowicz. After a thorough examination of the files, Kantorowicz came to the conclusion that Germany had been complicit in the outbreak of the war. He noted that three-fourths of the documents cited in The German White Book, published by the government in 1914 to support its claims regarding what had started the war, had been falsified.[23] Kantorowicz's expert opinion was not published until 1967.[23]

After the

Second subcommittee: missed peace opportunities

After the conclusion of the Treaty of Versailles, the issue of missed opportunities for peace during the war was hotly debated throughout the Weimar Republic. In the second subcommittee as well, the Foreign Office "succeeded in transforming the committee's work into a bureaucratically directed, quasi-secret investigation"[22] to which there was little resistance from the parliamentarians. As a result, only the reports on U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's peace campaign of 1916/17, Pope Benedict XV's mediation effort in the summer of 1917, peace feelers to France and Belgium, and the German-American peace talks in the spring of 1918 were brought to a conclusion. Possibilities for peace with Russia and Japan were not covered.

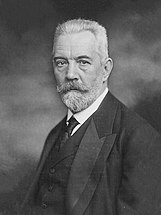

Committee chairman Fischer-Baling considered the handling of Wilson's peace feelers in 1916/17 to be the second most significant topic of the inquiry. The former Reich chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, former state secretary of foreign affairs Arthur Zimmermann, along with Hindenburg and Ludendorff were summoned. According to Fischer-Baling, it became apparent that the responsible politicians had recognized that the peace for which Wilson wanted to clear the way was a deliverance for Germany, but they were not allowed to reach for it because army leadership under Hindenburg and Ludendorff did not let them. Instead, by resuming unrestricted submarine warfare, the military ensured that the U.S. entered the war on the side of the Allies and helped to ensure Germany's defeat. In spite of its far-reaching findings, the subcommittee merely agreed on the result that "an important peace opportunity had not been treated with due diligence".[25] Since the committees were no longer meeting in public, the findings attracted little public attention.

The only matter that was viewed slightly differently was

After the

Third subcommittee: violations of international law

Under the original breakdown of each committee's tasks, it proved difficult for the third and fourth subcommittees to separate military and economic violations of international law. The two subcommittees agreed on 8 March 1920 that the third would "deal with all violations of international law pending investigation" and that the fourth would clarify "responsibility for the military and political collapse in the fall of 1918".[28]

The third committee hoped to clarify such issues as the violation of Belgian neutrality (the

The question of the violation of Belgian neutrality was dragged out and ultimately not brought to a resolution. Most committee members interpreted unrestricted submarine warfare, which violated prize laws for captured ships, as a legitimate response to the blockade of Germany by England in violation of international law. They also saw the forced transfer of Belgian workers to Germany as covered by the Hague Land Warfare Regulations, while they found clear violations of international law in the similar deportation of German residents of Alsace–Lorraine to France.[33]

In its assessment of the destruction caused by the German Army during its withdrawal from France and Belgium, the parliamentarians concluded that they were measures taken from a purely military point of view and were covered by Article 23 of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations. The conclusion was reached in spite of the fact that the committee had received an expert opinion prepared by the Foreign Office stating that such destruction "was entirely senseless and futile".[34]

Fourth subcommittee: causes of defeat

Beginning in November 1920, the fourth subcommittee worked on the questions of the origin, execution, and collapse of the German spring offensive of 1918, the grievances in the army, and the economic, social and moral grievances in the homeland and their repercussions on the army and navy. A month later, the work program was expanded to include the question of the subversive effect of domestic political events and propagandistic influences, both revolutionary and annexationist.[35]

Next to the second subcommittee, the fourth attracted the most public attention. It had the most difficult task and could have exposed the stab-in-the-back myth as self-interested propaganda, but there too the Weimar government coalition tried to maneuver between a real investigation and preventing admissions of guilt towards former opponents. Military authorities proved to be even more reluctant to release files than the Foreign Office. They made no secret of the fact that they opposed the parliamentary inquiry as a matter of principle.[36]

According to Fischer-Baling, it was clear from the documents the committee obtained that in October 1918 the Supreme Army Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff had repeated its call for an armistice with an urgency that remained deaf to Reich Chancellor

General Hermann von Kuhl, one of the leading general staff officers during the First World War, was appointed as the main expert on military issues. As a counterpart, the war historian Hans Delbrück was commissioned to provide another expert opinion. Fischer-Baling considered it a surprise that the expert reports revealed that there was no power that encompassed both the civil and military authorities other than the emperor. Moreover, it would have become apparent that no statesman would have approved the German spring offensive in March 1918 if "Ludendorff had presented the prospects to the chancellor with the sincerity that von Kuhl demonstrated before the subcommittee".[38] When Kuhl had finished with his account of the main offensive and the subsequent attacks in the spring and summer of 1918, he stated without contradiction that the war was lost. According to Fischer-Baling, his response answered the subcommittee's main question: The revolution had ended a war that in fact had been lost and was given up for lost by army leadership. The fact that the revolution and the democratic forces were later blamed for the defeat was merely an attempt after the fact to shift responsibility onto political opponents.[39]

The conclusions were disputed among the subcommittee members, but because they wanted to complete their work during the ongoing legislative period, they agreed in the spring of 1924 on a draft resolution that essentially endorsed the theses of the expert Delbrück but in which all points against Ludendorff were removed. In the newly constituted Reichstag, the nationalist DNVP, which until then had attempted to undermine the committee's work, advocated a continuation of the fourth subcommittee's inquiries. Albrecht Philipp of the DNVP and chairman of the fourth subcommittee justified the request by stating that the result was partisan and had to be corrected. The Reich Ministry of the Armed Forces also filed an objection. Chancellor Wilhelm Marx (Centre Party) resorted to a legal argument: the decision to publish all material had been taken by the subcommittee after the Reichstag had been dissolved in March 1924 and was therefore null and void. The subcommittee accepted the decision without appeal.[40]

In 1925 Hindenburg became president of the Reich. Ludendorff was able to brusquely refuse the summons to appear before the subcommittee without fear of being punished or brought before it. In May 1925 the deputies of the subcommittee submitted a significantly amended majority report and two minority reports. Most deputies bowed to increasing pressure and watered down the results they had found earlier. On the military collapse of 1918, they formulated that "no finding [can be] made which justifies arriving at a verdict of guilt on any side". In 1928, in the case of the investigation complex "Homeland Policy and the Subversion Movement (Stab-in-the-back Question)", the deputies came to the conclusion that "the blame for the German collapse can only be found in the mutual interaction of numerous causes".[41] Against the votes of the Social Democratic and Communist Party members, the subcommittee came out in favor of an acquittal of the Supreme Army Command.

With respect to the Navy's actions, the final report did not contain any criticism of naval command. The military had withheld from the deputies the war diary of the naval warfare command and a memorandum by Adolf von Trotha (then chief of staff of the High Seas Fleet), which clearly proved their intentions.[41]

End of the committee of inquiry

After the victory of the Nazi Party in July 1932 elections, the investigative committee was not reinstated. The Nazis thus prevented the completion of the first subcommittee's work by the representatives of the people. The question of responsibility for the military escalation of the July Crisis in 1914 which led to the outbreak of World War I could not be conclusively addressed. The public, however, took virtually no notice of it. In the eyes of the parliamentarians too, the committee's work had outlived its usefulness. Heinemann blamed the situation mainly on the ongoing intervention of the Foreign Office.[42]

See also

- Commission of Responsibilities of the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920)

- Historiography of the causes of World War I

Notes

References

- ^ Heinemann, Ulrich (1983). Die Verdrängte Niederlage. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Kriegsschuldfrage in der Weimarer Republik [The Repressed Defeat. Political Public Sphere and the Question of War Guilt in the Weimar Republic] (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 23.

- ^ Fischer-Baling, Eugen (1954). "Der Untersuchungsausschuß für die Schuldfragen des ersten Weltkrieges" [The Committee of Inquiry into the Culpability of the First World War]. In Herrmann, Alfred (ed.). Aus Geschichte und Politik. Festschrift für Ludwig Bergsträsser [From History and Politics. In Commemoration of Ludwig Bergsträsser] (in German). Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag. p. 118.

- ^ a b Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 118.

- ISBN 9783428079049.

- ^ – via Wikisource.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 155.

- ^ Anschütz, Gerhard. Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches vom 11. August 1919. Kommentar [Constitution of the German Reich of August 11, 1919. Commentary] (in German) (12 ed.). Berlin: G. Stilke. p. 199.

- ^ Heilfron, Eduard, ed. (1921). Die Deutsche Nationalversammlung im Jahre 1919 in ihrer Arbeit für den Aufbau des neuen deutschen Volksstaates [The German National Assembly in 1919 in its Work for the Establishment of the New German People's State] (in German). Berlin: Norddeutsche Buchdruckerei und Verlagsanstalt. pp. 150–153.

- ^ "Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstages: 84. Sitzung der Nationalversammlung vom 20. August 1919" [Proceedings of the German Reichstag: 84th Session of the National Assembly, 20 August 1919]. Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstags. p. 2798.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 123.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, pp. 260–267.

- ^ "Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstages, Verfassungsgebende Nationalversammlung, Aktenstück Nr. 1187: Mündlicher Bericht des 15. Ausschusses vom 14. Oktober 1919" [Proceedings of the German Reichstag, Constituent National Assembly, File No. 1187: Oral Report of the 15th Committee of 14 October 1919]. Verhandlungen des deutschen Reichstags. p. 1218.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, pp. 156 f.

- ^ Hahlweg, Werner, ed. (1971). Der Friede von Brest-Litowsk. Ein unveröffentlichter Band aus dem Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses der Deutschen Verfassunggebenden Nationalversammlung und des Deutschen Reichstages [The Peace of Brest-Litovsk. An Unpublished Volume from the Work of the Committee of Inquiry of the German Constituent National Assembly and the German Reichstag] (in German). Düsseldorf: Droste. pp. XV.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 119.

- ^ a b Heinemann 1983, p. 158.

- ^ Hahlweg 1971, p. XXVI.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (Spring 1938). "Ludendorff: The Soldier and the Politician". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 14 (2): 187–202.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 160–165.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 124.

- ^ a b Heinemann 1983, p. 204.

- ^ a b Heinemann 1983, p. 217.

- ^ a b Kantorowicz, Hermann; Geiss, Imanuel (1967). Gutachten zur Kriegsschuldfrage 1914 [Report on the War Guilt Question 1914] (in German). Frankfurt: Frankfurt Europäische Verlagsanstalt.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 136.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, pp. 124 f.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, pp. 27 f.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 173.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 177.

- ^ a b Heinemann 1983, p. 192.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 133.

- ^ a b "Part VII. Penalties". Treaty of Versailles. 1919 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 193.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, pp. 194 f.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 199.

- ^ Philipp, Albrecht, ed. (1925). Die Ursachen des Deutschen Zusammenbruchs im Jahre 1918. (= Das Werk des Untersuchungsausschusses der Deutschen Verfassungsgebenden Nationalversammlung und des Deutschen Reichstages 1919–1928. Vierte Reihe [The Causes of the German Collapse in 1918. (= The Work of the Committee of Inquiry of the German National Constituent Assembly and the German Reichstag 1919–1928. Fourth Series] (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin: Deutsche Verlag für Politik und Geschichte. p. 40.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 178.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 129.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 130.

- ^ Fischer-Baling 1954, p. 131.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, pp. 182 ff.

- ^ a b Heinemann 1983, p. 189.

- ^ Heinemann 1983, p. 190.