Sabuktakin

Sabuktakin or Sübüktegin was a

Life

Sabuktakin was a

Sabuktakin was one of a number of Turkic generals promoted to high office by Mu'izz al-Dawla as part of a policy designed to balance the dominant

Conflict with Bakhtiyar Izz al-Dawla

As part of the efforts to strike a balance between the two groups, Mu'izz al-Dawla in his testament explicitly recommended to Bakhtiyar to retain Sabuktakin in office.

In the meantime, Sabuktakin was able to use the widespread calls for

Uprising

These events made the breach between Sabuktakin and his ostensible master inevitable: following the advice of

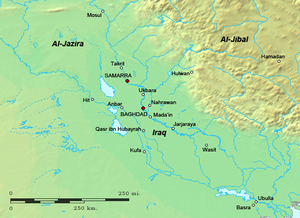

As the historian Hugh Kennedy comments, within a few months Sabuktakin had established what amounted to a Turkish emirate in Baghdad.[20] Sabuktakin appears initially to have been content with ruling over Baghdad, and proposed leaving southern Iraq to the Buyids, but this was evidently unacceptable to the Buyids and untenable in the long run, as it would leave the Turks sandwiched between the Hamdanids in the north and the Buyids in the south.[22] Before long, Sabuktakin and his forces marched on Wasit.[20]

Bakhtiyar's position at Wasit was saved by turning to his relatives in Iran for assistance.

Aftermath

Sabuktakin was succeeded by another ghulam, Alptakin, who lacked Sabuktakin's ability and was now faced with superior Buyid forces, which were joined by Arab bedouin tribes and the Hamdanids.[26] Defeated in January 975 near the Diyala River, Alptakin moved west to Damascus with about 300 of his followers.[27] Alptakin and his men ruled the city for a while, before they entered the service of the Fatimid Caliphate.[28] Buyid control over Baghdad was restored, but the events had severely shaken the foundation of Buyid power in the area, and Baghdad entered a period of decline that lasted for the rest of the Buyid era.[20][29]

Sabuktakin's utilization of anti-Shi'a sentiment in his conflict with the Buyids was also the first instance that the Turks as a people first became associated with the anti-Shi'a faction, presaging the policies of the

References

- ^ Busse 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 44 (note 146).

- ^ Bosworth 1975, p. 258.

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 36 (note 103).

- ^ Donohue 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 258–259, 329.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 195, 259.

- ^ Busse 2004, p. 259.

- ^ Donohue 2003, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Busse 2004, p. 329.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1975, p. 265.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 36, 334–335.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy 2004, p. 223.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 43.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Busse 2004, p. 198.

- ^ Busse 2004, p. 424.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Busse 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Busse 2004, p. 169.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Bosworth 1975, pp. 266, 267.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 206, 224.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 205–206, 224.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 206.

- ^ Busse 2004, pp. 399–400.

Sources

- ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Busse, Heribert (2004) [1969]. Chalif und Grosskönig - Die Buyiden im Irak (945-1055) [Caliph and Great King - The Buyids in Iraq (945-1055)] (in German). Würzburg: Ergon Verlag. ISBN 3-89913-005-7.

- Donohue, John J. (2003). The Buwayhid Dynasty in Iraq 334 H./945 to 403 H./1012: Shaping Institutions for the Future. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12860-3.

- ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.