Saint-Sauveur, Quebec City

Saint-Sauveur (French pronunciation:

History

Founding and settlementation

In the complete beginning of the French regime, the lowlands of the plain bordering the

The

The faubourg, which at the time formed part of the suburbs of Quebec City, was initially sparsely populated. In the 1840s, the neighbourhood is split into 4 big properties. The fief of the Recollects, which belonged to the Hôpital Général, along with the Domaine Bois-Bijou (Boisseauville), the land of the Hôtel-Dieu, and one plot which belonged to the Ursulines.[1]

In circa 1845, Boisseauville was founded as a result of surveying work. In the beginning, the Domaine Bois-Bijou was owned by Michel Sauvageau; it included a villa surrounded by a large garden, several barns and a pond. Michel Sauvageau had the first subdivision plan drawn up in 1810, and the first row of building lots was established on rue Sauvageau, towards the Faubourg Saint-Jean. After his death, Pierre Boisseau proceeded to subdivide the land on which Boisseauville would be built.[1]

This was followed by the construction of the first church and a town hall.

Working-class neighbourhood and urban development

Near the beginning of the 19th century, the success of the shipyards, timber trade and port activity led to the rapid development of Saint-Sauveur. The high demand for labour led to the construction of a large number of houses. Since 1840, Saint-Sauveur had become home to a large number of poor workers, because the building regulations in this area allowed for the construction of houses that were not fireproof. From 1845, Saint-Sauveur was considered a suburb of Quebec City. The fire that destroyed Saint-Roch in 1845 caused the population to migrate to Boisseauville.

The new municipal code of 1855 forced the small villages and towns of Quebec to assign themselves a municipality. Saint-Sauveur was grouped together with Limoilou to form a municipality known as the "suburb of Saint-Roch" until 1862. From a religious perspective, the Archbishop of Quebec transformed what had been a service of the parish of Saint-Roch into a fully-fledged parish in 1853.[2] He entrusted its management to the congregation of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. The neighbourhood obtained an autonomous municipal charter in 1862, and changed its official name from Saint-Roch Nord (North Saint-Roch) to Saint-Sauveur in 1872.[3]

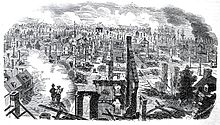

In 1866, Saint-Sauveur was razed by the Great Fire of Quebec City. That same year, the Langelier Boulevard was enlarged to prevent the fire from spreading between Saint-Roch and Saint-Sauveur.[3]

In 1888, the Marché Saint-Pierre was built on the site of today's Habitations Durocher. Named in the honor of Pierre Boisseau, it became the property of Quebec City when it annexed the village of Saint-Sauveur in 1889. The red brick hall was 51.82 meters long, the same size as Montcalm Hall.[4] It escaped the conflagration of 1889, which razed the neighbourhood to the ground. Closed in 1915, the building was rented out to Œuvres de Jeunesse, it then burned down in 1945.[5]

Another conflagration destroyed 600 homes on May 16, 1889. It was a devastating fire, that nearly destroyed the neighbourhood, and left around 5,000 people homeless.[1]

This reopened the debate on annexing the neighbourhood into Quebec City. The main issue was the installation of a water distribution network, which is essential for fighting fires. Talks between the two municipalities began in June 1889. The citizens of Saint-Sauveur ratified the agreement in a referendum held on September 26 and 27, 1889.[1] The Quebec City authorities moved into the neighbourhood, building sewers and pavements, along with paving and lighting streets.[3]

The transformation was quick.

In 1914,

On April 1, 1918, the neighbourhood is a theater in the Quebec City riot of 1918. That same year, the Spanish flu kills 500 people in Quebec City. 80% of the victims were in the Lower Town, especially in the poorer neighbourhoods. That being, Saint-Sauveur and Saint-Malo.[8]

Revitalization

In 1971, a campaign was launched to dismantle the railroad that ran through part of the neighbourhood and cut it off from the Parc Victoria. The tracks were finally removed in 1974.[9]

From 2006 to 2008, Quebec City undertook the project to completely remake the Charest Boulevard in between the Langelier Boulevard and the Saint-Sacrament Avenue. The thoroughfare underwent a major 2.5-kilometer overhaul, with the widening of sidewalks and the planting of trees. Several residential construction projects were also started in the same area.

The Saint-Charles River, to the north of the neighbourhood, underwent renaturalization work on its banks in 2007. The Parc Victoria is also transformed by the construction of a water retention basin, along with the demolition of the Victoria Arena and the relocation of a chapel.

List of mayors of Saint-Sauveur

- 1855–1858: Louis Falardeau

- 1858–?: Pierre Giroux

- ?–?: William Cook

- ?–?: François Falardeau

- 1870–1883: François Kirouac

- 1883–1884: Marcel Rochette

- 1884: Pierre Boutin

- 1885–1887: Michel Fiset

- 1887–1889: François Kirouac

- ?1901–1904: Émile Tourangeau[11]

Gallery

-

Chénier Street, near the Durocher Park.

-

Now-demolished building formerly occupied by the Durocher Community Center from 1950 to 2014.

-

Saint-Malo Heating Plant, in the industrial park of the same name.

-

Perspective from the Victoria Staircase.

References

- ^ ISBN 2-920860-03-8.

- ^ "Québec, Saint-Sauveur – OMI World" (in French). Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ S2CID 189971212. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- )

- ISSN 0714-9476. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ISSN 0829-7983. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ^ "Quebec – Arctic". laiteriesduquebec.com. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ISSN 0829-7983. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- ^ Lebel, Jean-Marie (2008). Québec 1608–2008: Les chroniques de la capitale (non-paginé). Québec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Gabriel Bernier (1978). Le quartier Saint-Sauveur de Québec: jalons historiques.

- ^ Division de la toponymie de la Ville de Québec. "Dolbeau, rue". ville.quebec.qc.ca. Retrieved 22 February 2023.