Spectrum disorder

Parts of this article (those related to documentation) need to be updated. The reason given is: Almost all of these sources are 15 years old, some of this information is notably and verifiably untrue as a result. (April 2023) |

A spectrum disorder is a

In some cases, a spectrum approach joins conditions that were previously considered separately. A notable example of this trend is the autism spectrum, where conditions on this spectrum may now all be referred to as autism spectrum disorders. A spectrum approach may also expand the type or the severity of issues which are included, which may lessen the gap with other diagnoses or with what is considered "normal". Proponents of this approach argue that it is in line with evidence of gradations in the type or severity of symptoms in the general population.

Origin

The term

The term was first used by

For different investigators, the hypothetical common disease-causing link has been of a different nature.[1]

Related concepts

A spectrum approach generally overlays or extends a categorical approach, which today is most associated with the

A spectrum approach sometimes starts with the nuclear, classic DSM diagnostic criteria for a disorder (or may join several disorders), and then include an additional broad range of issues such as temperaments or traits, lifestyle, behavioral patterns, and personality characteristics.[1]

In addition, the term 'spectrum' may be used interchangeably with

An example can be found in personality or

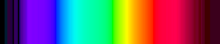

A spectrum approach, by comparison, suggests that although there is a common underlying link, which could be continuous, particular sets of individuals present with particular patterns of symptoms (i.e. syndrome or subtype), reminiscent of the visible spectrum of distinct colors after refraction of light by a prism.[1]

It has been argued that within the data used to develop the DSM system there is a large literature leading to the conclusion that a spectrum classification provides a better perspective on phenomenology (appearance and experience) of psychopathology (mental difficulties) than a categorical classification system. However, the term has a varied history, meaning one thing when referring to a schizophrenia spectrum and another when referring to bipolar or obsessive–compulsive disorder spectrum, for example.[1]

Types of spectrum

The widely used DSM and ICD manuals are generally limited to categorical diagnoses. However, some categories include a range of subtypes which vary from the main diagnosis in clinical presentation or typical severity. Some categories could be considered subsyndromal (not meeting criteria for the full diagnosis) subtypes. In addition, many of the categories include a 'not otherwise specified' subtype, where enough symptoms are present but not in the main recognized pattern; in some categories this is the most common diagnosis.

Spectrum concepts used in research or clinical practice include the following.[1]

Anxiety, stress, and dissociation

Several types of spectrum are in use in these areas, some of which are being considered in the DSM-5.[6]

A

A social anxiety spectrum[8] – this has been defined to span shyness to social anxiety disorder, including typical and atypical presentations, isolated signs and symptoms, and elements of avoidant personality disorder.

A

A

– work in this area has sought to go beyond the DSM category and consider in more detail a spectrum of severity of symptoms (rather than just presence or absence for diagnostic purposes), as well as a spectrum in terms of the nature of the stressor (e.g. the traumatic incident) and a spectrum of how people respond to trauma. This identifies a significant amount of symptoms and impairment below threshold for DSM diagnosis but nevertheless important, and potentially also present in other disorders a person might be diagnosed with.A depersonalization-derealization spectrum[12][13] – although the DSM identifies only a chronic and severe form of depersonalization disorder, and the ICD a 'depersonalization-derealization syndrome', a spectrum of severity has long been identified, including short-lasting episodes commonly experienced in the general population and often associated with other disorders.

Obsessions and compulsions

An

General developmental disorders

An autistic spectrum

Schizophrenia spectrum

The

- Five subtypes of schizophrenia (although eliminated in DSM-5)

- Two forms of shorter duration (schizophreniform disorder and brief psychotic disorder)

- three delusional disorders (persistent shared psychotic disorder, other delusional disorders)

- Schizoaffective disorder: symptoms of schizophrenia and a mood disorder (depression or bipolar disorder)

- Catatonia

- Schizotypal personality disorder

- Other and unspecified non-organic psychotic disorders (Atypical psychosis), (inc: chronic hallucinatory psychosis)

Predisposition to schizophrenia is classified with the neologism schizotaxia.[23] There are also traits identified in first degree relatives of those diagnosed with schizophrenia associated with the spectrum.[24] Other spectrum approaches include more specific individual phenomena which may also occur in non-clinical forms in the general population, such as some paranoid beliefs or hearing voices. Psychosis accompanied by mood disorder may be included as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, or may be classed separately as below.

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders do not necessarily involve psychotic symptoms. Schizoid personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, and paranoid personality disorder can be considered 'schizophrenia-like personality disorders' because of their similarities to the schizophrenia spectrum.[25] Some researchers have also proposed that avoidant personality disorder and related social anxiety traits should be considered part of a schizophrenia spectrum.[26]

From a

Schizoaffective disorders

A

Mood

A

In another direction, numerous links and overlaps have been found between major depressive disorder and bipolar syndromes, including

Substance use

A spectrum of

Paraphilias and obsessions

The interpretative key of "spectrum," developed from the concept of "related disorders," has been considered also in paraphilias.[clarification needed]

Paraphilic behavior is triggered by thoughts or urges that are psychopathologically close to obsessive impulsive area. Hollander (1996) includes in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum neurological obsessive disorders, body-perception-related disorders and impulsivity-compulsivity disorders. In this continuum from impulsivity to compulsivity it is particularly hard to find a clear borderline between the two entities.[37]

On this point of view, paraphilias represent such as sexual behaviors due to a high impulsivity-compulsivity drive. It is difficult to distinguish impulsivity from compulsivity: Sometimes paraphilic behaviors are prone to achieve pleasure (desire or fantasy); in some other cases, these attitudes are merely expressions of anxiety, and the atypical behavior is an attempt to reduce anxiety. In the last case, the pleasure gained is short in time and is followed by a new increase in anxiety levels, such as it can be seen in an obsessive patient after he performs his compulsion.[citation needed]

Eibl-Eibelsfeldt (1984) underlines a female sexual arousal condition during flight and fear reactions. Some women, with masochistic traits, can reach orgasm in such conditions.[38]

Broad spectrum approach

Various higher-level types of spectrum have also been proposed, that subsume conditions into fewer but broader overarching groups.[1]

One psychological model based on

Similar approaches refer to the overall "architecture" or "meta-structure," particularly in relation to the development of the DSM or ICD systems. Five proposed meta-structure groupings were recently proposed in this way, based on views and evidence relating to risk factors and clinical presentation. The clusters of disorder that emerged were described as neurocognitive (identified mainly by neural substrate abnormalities), neurodevelopmental (identified mainly by early and continuing cognitive deficits), psychosis (identified mainly by clinical features and biomarkers for information processing deficits), emotional (identified mainly by being preceded by a temperament of negative emotionality), and externalizing (identified mainly be being preceded by disinhibition).[42] However, the analysis was not necessarily able to validate one arrangement over others. From a psychological point of view, it has been suggested that the underlying phenomena are too complex, inter-related and continuous – with too poorly understood a biological or environmental basis – to expect that everything can be mapped into a set of categories for all purposes. In this context the overall system of classification is to some extent arbitrary, and could be thought of as a user interface which may need to satisfy different purposes.[43]

See also

- Classification of mental disorder

- Psychopathology

- Abnormal psychology

- Neurodiversity

- Mentalism (discrimination)

- Recovery approach

External links

- A Video Introduction to RDoC (Research Domain Criteria): A Spectrum or Dimensional Approach to Understanding and Classifying Mental Disorders from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (2013)

- Spectrum and nosology: implications for DSM-V

- Collection of standardized questionnaires from the Italy-USA collaborative spectrum project

- Psychiatric Clinics of North America Special Issue on Spectrum Concepts (2002)

References

- ^ PMID 12462854.

- ^ PMID 17329735.

- PMID 19293948.

- PMID 18235857.

- S2CID 29033682.

- ^ "Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. May 17, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015.

- S2CID 12582240.

- S2CID 30944382.

- PMID 11287057.

- PMID 12462860.

- PMID 18226228.

- PMID 19183789.

- PMID 7961531.

- PMID 3221332.

- PMID 12462862.

- PMID 11144346.

- PMID 17967920.

- PMID 12944332.

- ISBN 978-0-521-85056-8.[page needed]

- S2CID 34887558.

- ^ Daisy Yuhas (2013). "Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Has Remained a Challenge". Scientific American Mind. Archived from the original on 2013-04-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - PMID 11215539.

- ^ Stephan Heckers (2009) Neurobiology of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Annals of Medicine, Vol 38, No.5

- ISBN 978-0-19-518980-3. Schizophrenia-like Personality Disorders. p. 240.

- PMID 17306508.

- ^ ISBN 9781609184940.

- ISBN 9781462530557.

- PMID 18029027.

- .

- S2CID 144069196.

- PMID 9268773.

- PMID 16488021.

- ^ Berrocal C, Ruiz Moreno MA, Rando MA, Benvenuti A, Cassano GB. (2008) Borderline personality disorder and mood spectrum. Psychiatry Res. 2008 Jun 30;159(3):300–7.

- ^ A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada (2005)

- PMID 15714188.

- ^ E. Hollander: Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders, 1996

- ^ I, Eibl-Eibelsfeldt Die Biologie des menschlichen Verhaltens. Grundriß der Humanethologie, Monaco 1984

- PMID 18392116.

- PMID 16330723.

- PMID 16730070.

- ^ Various (2009). "Thematic section: A proposal for a meta-structure for DSM-V and ICD-11) – 2009". Psychological Medicine Volume 39 – Issue 12. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- doi:10.1037/a0021701.