Synagogue (John Singer Sargent)

| Synagogue | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | John Singer Sargent |

| Year | 1919 |

Synagogue is an allegorical mural by John Singer Sargent in the Boston Public Library.[1] It is part of Sargent's larger Triumph of Religion mural cycle in the library's central branch at Copley Square. Synagogue was unveiled in 1919, and it sparked immediate controversy.[2] The cowering and feeble personification of the Synagogue stood in contrast with Sargent's glorified depiction of the Church in the mural cycle, and members of the Jewish community observed that the series delivered an implicit message of Jewish decline and Christian triumph.[2] Sargent was reluctant to respond publicly to criticism of the work, but privately wrote in 1919, "I am in hot water with the Jews, who resent my ‘Synagogue,’ and want to have it removed– and tomorrow a ‘prominent’ member of the Jewish colony is coming to bully me about it and ask me to explain myself. I can only refer him to Rheims, Notre Dame, Strasbourg and other Cathedrals, and dwell at length about the good old times."[2]: 233 Responding to charges that the work was antisemitic, the Massachusetts legislature passed a bill ordering the removal of the mural in 1922, but the law was soon repealed, and the work has remained in place.[2]: 236

Background: Triumph of Religion

The Triumph of Religion is a commissioned work by Sargent at the Boston Public Library. In official correspondence with the library, Sargent described it as "Triumph of Religion—a mural decoration illustrating certain stages of Jewish and Christian religious history." Designed and painted in London, the cycle is divided into 17 works that were transferred to Boston in installments. Sargent began sketching the murals in 1891, and the cycle remained unfinished at the time of his death in 1925.[3]

Synagogue and its counterpart, Church, appear on the East wall, on either side of a space reserved for a depiction of Jesus giving the Sermon on the Mount, which was never finished.[2]

Iconography

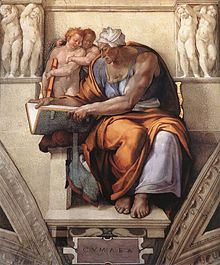

Scholars have identified many themes and influences in the larger mural cycle. Sally M. Promey identifies three key themes: individualism and subjectivity overcoming law and doctrine; a reaction to World War I; and concealment and revelation. She also notes the visual similarity between Synagogue and the Cumaean Sibyl in Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel.[2] Sargent also may have been influenced by the writing of Ernest Renan.[2]

Antisemitism controversy

Even before Synagogue was unveiled to the public, there were already fears about Sargent's handling of the religious subject matter. Promey writes that prior to the mural’s installment, Boston Herald critic Frederick William Coburn opined that "in the interest of racial and religious amenity in this community, one hopes that Mr. Sargent has avoided the old middle-age bigotry in working out this perilous theme, as no doubt he has done."[4] Given the antisemitism and immigration restriction of the 1920's, Sargent’s treatment of religion had the potential to be extremely divisive.[2] Indeed, after the painting was revealed, many viewers did find it offensive, and there were numerous attempts to remove it in subsequent years.[4]

Ideological criticisms

Critics of the painting objected to the representation of the Synagogue as a huddled woman wearing a blindfold, especially next to the representation of the Christian church, a pietà. Many saw the painting as representing a triumph of Christianity, rather than one of religion.[4] Leo Franklin, the President of Reform Judaism’s Central Conference found that the painting presented "Judaism as a broken faith, as a faith without a future," and therefore should not be placed in a public library.[4] This depiction of Judaism, in addition to being offensive, was also historically inaccurate. Massachusetts State Representative Coleman Silbert wrote that the representation “represent[ed] Judaism as downfallen or dead, which is far from the truth... it is against the broad spirit of Americanism."[4] Artist Rose Kohler also found the work to be un-American, writing that "it was felt that in this century and in America, we had advanced sufficiently to cast aside the notions and prejudices of the dark ages."[4] She also designed a monument in response to Sargent’s painting, a medallion entitled Spirit of the Synagogue, which depicted the Synagogue figure as upright and triumphant.[4]

Due to the antisemitic nature of the painting, many asserted that it was inappropriately placed in a public, educational building. The rabbi Henry Raphael Gold found its placement to be unfair to Jewish students.[4] Coburn called the placement of such a mural "distasteful… in a building supported by public taxation."[4]

Proposed removal

The first attempt to remove the painting occurred just after it was unveiled in 1919, when local citizens circulated an unsuccessful petition.[4]

Shortly after, many organizations wrote to the library, arguing for the removal of the painting. These included the

In 1922, Representative Silbert introduced a bill that would allow the state to remove the painting, which passed in the Senate and was signed by the Governor. The bill would have seized the painting by right of eminent domain. However, the bill was struck down as unconstitutional, and repealed in 1924.[4]

On February 2, 1924, The New York Times reported that a "black, inklike substance" was thrown on the painting.[5]

Defense and Sargent's response

Sargent himself, averse to controversy and public statements, said little to the press about the controversy. One Boston newspaper reported in 1922 that he "made it known through a friend that no reflection on the Jewish race was intended."[4]: 189 Privately, he asserted that the painting was justified due to its medieval precedent, and expressed gratitude that the library allowed it to remain.[4]

After the installation of Synagogue, the final panel of the cycle, a representation of the Sermon on the Mount, was never installed.[6] Although it could be argued that Sargent’s death caused the mural to remain unfinished, Promey notes that Sargent never tried to collect his final payment for the mural, pointing towards the fact that he had stopped working on it.[4]

The American Fine Art Society, following the controversy, passed a resolution defending Sargent, and American Art News wrote that, "whether judiciously chosen or not, the subject was historically correct. It belonged logically in the series."[4]

Present status

The painting remains visible in the Boston Public Library today. Between 2003 and 2004, the Triumph of Religion cycle was restored by the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard University.[7]

See also

References

- ^ "Synagogue". Digital Commonwealth. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ JSTOR 3046244.

- ^ Farrell, Eugene; Olivier, Kate; Hensick, Teri (1998). "John Singer Sargent's Forgotten Mural Cycle, The Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library". Studies in Conservation (43).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Promey, Sally, M. (1999). Painting Religion in Public : John Singer Sargent's Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 176–225.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ink or Paint is Spattered on the 'Synagogue' Sargent Painting That Caused Row in Boston". The New York Times. February 22, 1924. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Promey, Sally M (1998). "The Afterlives of Sargent's Prophets". Art Journal (57): 31–44.

- ^ "Central Library: McKim Building Points of Interest". Boston Public Library. Retrieved April 6, 2023.