Ukraine

Ukraine Україна (Ukrainian) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Державний Гімн України Derzhavnyi Himn Ukrainy " | |

| Demonym(s) | Ukrainian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Volodymyr Zelenskyy | |

| Denys Shmyhal | |

| Ruslan Stefanchuk | |

| Legislature | Verkhovna Rada |

| Formation | |

| 882 | |

| 1199 | |

| 18 August 1649 | |

| 20 November 1917 | |

| 10 March 1919 | |

| 24 October 1945 | |

| 24 August 1991 | |

| 28 June 1996 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 603,628[4] km2 (233,062 sq mi) (45th) |

• Water (%) | 3.8[5] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 60.9/km2 (157.7/sq mi) (126th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2022) | high (100th) |

| Currency | Hryvnia (₴) (UAH) |

| Time zone | UTC+2[9] (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +380 |

| ISO 3166 code | UA |

| Internet TLD | |

Ukraine[a] is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which borders it to the east and northeast.[b][10] It also borders Belarus to the north; Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary to the west; and Romania and Moldova[c] to the southwest; with a coastline along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov to the south and southeast.[d] Kyiv is the nation's capital and largest city, followed by Kharkiv, Dnipro and Odesa. Ukraine's official language is Ukrainian; Russian is also widely spoken, especially in the east and south.

During the

Ukraine gained independence in 1991 as the

Ukraine is a unitary state and its system of government is a semi-presidential republic. A developing country, it is the poorest country in Europe by nominal GDP per capita[15] and corruption remains a significant issue.[16] However, due to its extensive fertile land, pre-war Ukraine was one of the largest grain exporters in the world.[17][18] It is a founding member of the United Nations, as well as a member of the Council of Europe, the World Trade Organization, and the OSCE. It is in the process of joining the European Union and has applied to join NATO.[19]

Etymology and orthography

The

Another interpretation is that the name of Ukraine means "region" or "country."In the English-speaking world during most of the 20th century, Ukraine (whether independent or not) was referred to as "the Ukraine".[21] This is because the word ukraina means 'borderland'[22] so the definite article would be natural in the English language; this is similar to Nederlanden, which means 'low lands' and is rendered in English as "the Netherlands".[23] However, since Ukraine's declaration of independence in 1991, this usage has become politicised and is now rarer, and style guides advise against its use.[24][25] US ambassador William Taylor said that using "the Ukraine" implies disregard for Ukrainian sovereignty.[26] The official Ukrainian position is that "the Ukraine" is both grammatically and politically incorrect.[27][28]

History

Early history

1.4 million year old stone tools from

From the 6th century BC,

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the

Golden Age of Kyiv

The establishment of the state of

During the 10th and 11th centuries, Kievan Rus' became the largest and most powerful state in Europe, a period known as its Golden Age.

The

Foreign domination

Crown of the Kingdom of Poland

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Duchy of Livonia

Duchy of Prussia, Polish fief

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, Commonwealth fief

In 1349, in the aftermath of the

In 1569, the

Cossack Hetmanate

Deprived of native protectors among the Ruthenian nobility, the peasants and townspeople began turning for protection to the emerging

In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky led the largest of the Cossack uprisings against the Commonwealth and the Polish king, which enjoyed wide support from the local population.[66] Khmelnytsky founded the Cossack Hetmanate, which existed until 1764 (some sources claim until 1782).[67] After Khmelnytsky suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Berestechko in 1651, he turned to the Russian tsar for help. In 1654, Khmelnytsky was subject to the Pereiaslav Agreement, forming a military and political alliance with Russia that acknowledged loyalty to the Russian monarch.

After his death, the Hetmanate went through a devastating 30-year war amongst Russia, Poland, the

The Hetmanate's autonomy was severely restricted since Poltava. In the years 1764–1781,

in 1795.19th and early 20th century

The 19th century saw the rise of Ukrainian nationalism. With growing urbanization and modernization and a cultural trend toward

Ukraine, like the rest of the Russian Empire, joined the

Ukraine plunged into turmoil with the beginning of

An attempt to create an independent state, the left-leaning Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR), was first announced by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, but the period was plagued by an extremely unstable political and military environment. It was first deposed in a coup d'état led by Pavlo Skoropadskyi, which yielded the Ukrainian State under the German protectorate, and the attempt to restore the UNR under the Directorate ultimately failed as the Ukrainian army was regularly overrun by other forces. The short-lived West Ukrainian People's Republic and Hutsul Republic also failed to join the rest of Ukraine.[83]

The result of the conflict was a partial victory for the Second Polish Republic, which annexed the Western Ukrainian provinces, as well as a larger-scale victory for the pro-Soviet forces, which succeeded in dislodging the remaining factions and eventually established the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Soviet Ukraine). Meanwhile, modern-day Bukovina was occupied by Romania and Carpathian Ruthenia was admitted to Czechoslovakia as an autonomous region.[84]

The conflict over Ukraine, a part of the broader Russian Civil War, devastated the whole of the former Russian Empire, including eastern and central Ukraine. The fighting left over 1.5 million people dead and hundreds of thousands homeless in the former Russian Empire's territory. The eastern provinces were additionally impacted by a famine in 1921.[85][86]

Inter-war period

During the inter-war period, in Poland, Marshal Józef Piłsudski sought Ukrainian support by offering local autonomy as a way to minimise Soviet influence in Poland's eastern Kresy region.[87][88] However, this approach was abandoned after Piłsudski's death in 1935, due to continued unrest among the Ukrainian population, including assassinations of Polish government officials by the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN); with the Polish government responding by restricting rights of people who declared Ukrainian nationality.[89][90] In consequence, the underground Ukrainian nationalist and militant movement, which arose in the 1920s gained wider support.

Meanwhile, the recently constituted Soviet Ukraine became one of the founding republics of the

Around the same time, Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin instituted the New Economic Policy (NEP), which introduced a form of market socialism, allowing some private ownership of small and medium-sized productive enterprises, hoping to reconstruct the post-war Soviet Union that had been devastated by both WWI and later the civil war. The NEP was successful at restoring the formerly war-torn nation to pre-WWI levels of production and agricultural output by the mid-1920s, much of the latter based in Ukraine.[92] These policies attracted many prominent former UNR figures, including former UNR leader Hrushevsky, to return to Soviet Ukraine, where they were accepted, and participated in the advancement of Ukrainian science and culture.[93]

This period was cut short when

However, as a consequence of Stalin's new policy, the Ukrainian peasantry suffered from the

Following on the Russian Civil War and collectivisation, the Great Purge, while killing Stalin's perceived political enemies, resulted in a profound loss of a new generation of Ukrainian intelligentsia, known today as the Executed Renaissance.[95]

World War II

Following the

Although the majority of Ukrainians fought in or alongside the Red Army and

In total, the number of ethnic Ukrainians who fought in the ranks of the Soviet Army is estimated from 4.5 million

The vast majority of the fighting in World War II took place on the Eastern Front.[116] The total losses inflicted upon the Ukrainian population during the war are estimated at 6 million,[117][118] including an estimated one and a half million Jews killed by the Einsatzgruppen,[119] sometimes with the help of local collaborators. Of the estimated 8.6 million Soviet troop losses,[120][121][122] 1.4 million were ethnic Ukrainians.[120][122][e][f] The Victory Day is celebrated as one of eleven Ukrainian national holidays.[123]

Post–war Soviet Ukraine

The republic was heavily damaged by the war, and it required significant efforts to recover. More than 700 cities and towns and 28,000 villages were destroyed.

Following the death of Stalin in 1953,

By 1950, the republic had fully surpassed pre-war levels of industry and production.[131] Soviet Ukraine soon became a European leader in industrial production[132] and an important centre of the Soviet arms industry and high-tech research, though heavy industry still had an outsided influence.[133] The Soviet government invested in hydroelectric and nuclear power projects to cater to the energy demand that the development carried. On 26 April 1986, however, a reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded, resulting in the Chernobyl disaster, the worst nuclear reactor accident in history.[134]

Independence

Ukraine was initially viewed as having favourable economic conditions in comparison to the other regions of the Soviet Union,

From the political perspective, one of the defining features of the

Even though Russia had signed the

The military conflict with Russia shifted the government's policy towards the West. Shortly after Yanukovych fled Ukraine, the country signed the EU association agreement in June 2014, and its citizens were granted visa-free travel to the European Union three years later. In January 2019, the

Geography

Ukraine is the second-largest European country, after Russia. Lying between latitudes 44° and 53° N, and longitudes 22° and 41° E., it is mostly in the East European Plain. Ukraine covers an area of 603,550 square kilometres (233,030 sq mi), with a coastline of 2,782 kilometres (1,729 mi).[49]

The landscape of Ukraine consists mostly of fertile

Ukraine also has a number of highland regions such as the

Significant natural resources in Ukraine include

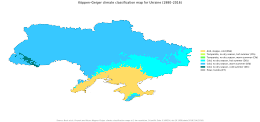

]Climate

Ukraine is in the mid-latitudes, and generally has a

Water availability from the major river basins is expected to decrease due to climate change, especially in summer. This poses risks to the agricultural sector.[187] The negative impacts of climate change on agriculture are mostly felt in the south of the country, which has a steppe climate. In the north, some crops may be able to benefit from a longer growing season.[188] The World Bank has stated that Ukraine is highly vulnerable to climate change.[189]

Biodiversity

Ukraine contains six terrestrial

Urban areas

Ukraine has 457 cities, of which 176 are designated as oblast-class, 279 as smaller raion-class cities, and two as special legal status cities. There are also 886 urban-type settlements and 28,552 villages.[196]

Rank

|

Name | Region

|

Pop.

|

Rank

|

Name | Region

|

Pop. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kyiv  Kharkiv |

1 | Kyiv | Kyiv (city) | 2,952,301 | 11 | Mariupol | Donetsk | 425,681 |  Odesa  Dnipro |

| 2 | Kharkiv | Kharkiv | 1,421,125 | 12 | Luhansk | Luhansk | 397,677 | ||

| 3 | Odesa | Odesa | 1,010,537 | 13 | Vinnytsia | Vinnytsia | 369,739 | ||

| 4 | Dnipro | Dnipropetrovsk | 968,502 | 14 | Simferopol | Crimea |

340,540 | ||

| 5 | Donetsk | Donetsk | 901,645 | 15 | Makiivka | Donetsk | 338,968 | ||

| 6 | Lviv | Lviv | 717,273 | 16 | Chernihiv | Chernihiv | 282,747 | ||

| 7 | Zaporizhzhia | Zaporizhzhia | 710,052 | 17 | Poltava | Poltava | 279,593 | ||

| 8 | Kryvyi Rih | Dnipropetrovsk | 603,904 | 18 | Kherson | Kherson | 279,131 | ||

| 9 | Sevastopol | Sevastopol (city) | 479,394 | 19 | Khmelnytskyi | Khmelnytskyi | 274,452 | ||

| 10 | Mykolaiv | Mykolaiv | 470,011 | 20 | Cherkasy | Cherkasy | 269,836 | ||

Politics

Ukraine is a republic under a

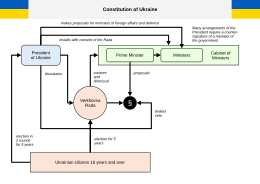

Constitution

The Constitution of Ukraine was adopted and ratified at the 5th session of the Verkhovna Rada, the parliament of Ukraine, on 28 June 1996.[199] The constitution was passed with 315 ayes out of 450 votes possible (300 ayes minimum).[199] All other laws and other normative[clarification needed] legal acts of Ukraine must conform to the constitution. The right to amend the constitution through a special legislative procedure is vested exclusively in the parliament. The only body that may interpret the constitution and determine whether legislation conforms to it is the Constitutional Court of Ukraine. Since 1996, the public holiday Constitution Day is celebrated on 28 June.[200][201] On 7 February 2019, the Verkhovna Rada voted to amend the constitution to state Ukraine's strategic objectives as joining the European Union and NATO.[202]

Government

The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and is the formal head of state.[203] Ukraine's legislative branch includes the 450-seat

Laws, acts of the parliament and the cabinet, presidential decrees, and acts of the Crimean parliament may be abrogated by the Constitutional Court, should they be found to violate the constitution. Other normative acts are subject to judicial review. The Supreme Court is the main body in the system of courts of general jurisdiction. Local self-government is officially guaranteed. Local councils and city mayors are popularly elected and exercise control over local budgets. The heads of regional and district administrations are appointed by the president in accordance with the proposals of the prime minister.[207]

Courts and law enforcement

Martial law was declared when Russia invaded in February 2022,[208] and continues.[209][210] The courts enjoy legal, financial and constitutional freedom guaranteed by Ukrainian law since 2002. Judges are largely well protected from dismissal (except for gross misconduct). Court justices are appointed by presidential decree for an initial period of five years, after which Ukraine's Supreme Council confirms their positions for life. Although there are still problems, the system is considered to have been much improved since Ukraine's independence in 1991. The Supreme Court is regarded as an independent and impartial body, and has on several occasions ruled against the Ukrainian government. The World Justice Project ranks Ukraine 66 out of 99 countries surveyed in its annual Rule of Law Index.[211]

In 2010, President Yanukovych formed an expert group to make recommendations on how to "clean up the current mess and adopt a law on court organization".[214] One day later, he stated "We can no longer disgrace our country with such a court system."[214] The criminal judicial system and the prison system of Ukraine remain quite punitive.[215]

Since 2010 court proceedings can be held in Russian by mutual consent of the parties. Citizens unable to speak Ukrainian or Russian may use their native language or the services of a translator.[216][217] Previously all court proceedings had to be held in Ukrainian.[215]

Law enforcement agencies are controlled by the

Foreign relations

From 1999 to 2001, Ukraine served as a non-permanent member of the

Ukraine considers Euro-Atlantic integration its primary foreign policy objective,

In 1992, Ukraine joined the then-Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (now the

Ukraine is the most active member of the

In 2020, in

In 2021, the

Military

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine inherited a 780,000-man military force on its territory, equipped with the third-largest

Ukraine took consistent steps toward reduction of conventional weapons. It signed the

Ukraine played an increasing role in peacekeeping operations. In 2014, the Ukrainian frigate Hetman Sagaidachniy joined the European Union's counter piracy

Following independence, Ukraine declared itself a neutral state.

As part of modernization after the beginning of the

Administrative divisions

The system of Ukrainian subdivisions reflects the country's status as a unitary state (as stated in the country's constitution) with unified legal and administrative regimes for each unit.

Including Sevastopol and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea that were annexed by the Russian Federation in 2014, Ukraine consists of 27 regions: twenty-four oblasts (provinces), one autonomous republic (Autonomous Republic of Crimea), and two cities of special status—Kyiv, the capital, and Sevastopol. The 24 oblasts and Crimea are subdivided into 136[242] raions (districts) and city municipalities of regional significance, or second-level administrative units.

Populated places in Ukraine are split into two categories: urban and rural. Urban populated places are split further into cities and urban-type settlements (a Soviet administrative invention), while rural populated places consist of villages and settlements (a generally used term). All cities have a certain degree of self-rule depending on their significance such as national significance (as in the case of Kyiv and Sevastopol), regional significance (within each oblast or autonomous republic) or district significance (all the rest of cities). A city's significance depends on several factors such as its population, socio-economic and historical importance and infrastructure.

| Oblasts | |

|---|---|

| Autonomous republic | Cities with special status

|

Economy

In 2021, agriculture was the biggest sector of the economy. Ukraine is one of the world's

In 2021, the average salary in Ukraine reached its highest level at almost

In 2021 mineral commodities and light industry were important sectors.[253] Ukraine produces nearly all types of transportation vehicles and spacecraft.[254][255][256] Antonov airplanes and KrAZ trucks are exported to many countries. The European Union is the country's main trade partner, and remittances from Ukrainians working abroad are important.[253]

Agriculture

Ukraine is among the world's top agricultural producers and exporters and is often described as the "bread basket of Europe". During the 2020/21 international wheat marketing season (July–June), it ranked as the sixth largest wheat exporter, accounting for nine percent of world wheat trade.[257] The country is also a major global exporter of maize, barley and rapeseed. In 2020/21, it accounted for 12 percent of global trade in maize and barley and for 14 percent of world rapeseed exports. Its trade share is even greater in the sunflower oil sector, with the country accounting for about 50 percent of world exports in 2020/2021.[257]

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), further to causing the loss of lives and increasing humanitarian needs, the likely disruptions caused by the Russo-Ukrainian War to Ukraine's grain and oilseed sectors, could jeopardize the food security of many countries, especially those that are highly dependent on Ukraine and Russia for their food and fertilizer imports.[258] Several of these countries fall into the Least Developed Country (LDC) group, while many others belong to the group of Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries (LIFDCs).[259][260] For example Eritrea sourced 47 percent of its wheat imports in 2021 from Ukraine. Overall, more than 30 nations depend on Ukraine and the Russian Federation for over 30 percent of their wheat import needs, many of them in North Africa and Western and Central Asia.[257]

Tourism

Before the

Transport

Many roads and bridges were destroyed, and international maritime travel was blocked by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[246] Before that it was mainly through the Port of Odesa, from where ferries sailed regularly to Istanbul, Varna and Haifa. The largest ferry company operating these routes was Ukrferry.[263] There are over 1,600 km (1,000 mi) of navigable waterways on 7 rivers, mostly on the Danube, Dnieper and Pripyat. All Ukraine's rivers freeze over in winter, limiting navigation.[264]

Ukraine International Airlines, is the flag carrier and the largest airline, with its head office in Kyiv[267] and its main hub at Kyiv's Boryspil International Airport. It operated domestic and international passenger flights and cargo services to Europe, the Middle East, the United States,[230] Canada,[268] and Asia.

Energy

Energy in Ukraine is mainly from gas and coal, followed by nuclear then oil.[171] The coal industry has been disrupted by conflict.[269] Most gas and oil is imported, but since 2015 energy policy has prioritised diversifying energy supply.[270]

About half of electricity generation is nuclear and a quarter coal.[171] The largest nuclear power plant in Europe, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, is in Ukraine. Fossil fuel subsidies were US$2.2 billion in 2019.[271] Until the 2010s all of Ukraine's nuclear fuel came from Russia, but now most does not.[272]

Some energy infrastructure was destroyed in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[273][274] The contract to transit Russian gas expires at the end of 2024.[275]

In early 2022 Ukraine and Moldova decoupled their electricity grids from the Integrated Power System of Russia and Belarus; and the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity synchronized them with continental Europe.[276][277]

Information technology

Key officials may use Starlink as backup.[278] The IT industry contributed almost 5 per cent to Ukraine's GDP in 2021[279] and in 2022 continued both inside and outside the country.[280]

Demographics

Source: Ethnic composition of the population of Ukraine, 2001 Census

Before the

Following the

According to the

Outside the former Soviet Union, the largest source of incoming immigrants in Ukraine's post-independence period was from four Asian countries, namely China, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Language

According to Ukraine's constitution, the

Effective in August 2012,

In 2014, following the

Ukrainian is the primary language used in the vast majority of Ukraine. 67% of Ukrainians speak Ukrainian as their primary language, while 30% speak Russian as their primary language.[303] In eastern and southern Ukraine, Russian is the primary language in some cities, while Ukrainian is used in rural areas. Hungarian is spoken in Zakarpattia Oblast.[304] There is no consensus among scholars whether Rusyn, also spoken in Zakarpattia, is a distinct language or a dialect of Ukrainian.[305] The Ukrainian government does not recognise Rusyn and Rusyns as a distinct language and people.[306]

For a large part of the Soviet era, the number of Ukrainian speakers declined from generation to generation, and by the mid-1980s, the usage of the Ukrainian language in public life had decreased significantly.

Diaspora

The Ukrainian diaspora comprises Ukrainians and their descendants who live outside Ukraine around the world, especially those who maintain some kind of connection to the land of their ancestors and maintain their feeling of Ukrainian national identity within their own local community.[313] The Ukrainian diaspora is found throughout numerous regions worldwide including other post-Soviet states as well as in Canada,[314] and other countries such as Poland,[315] the United States,[316] the UK[317][318] and Brazil.[319]

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to

Religion

Ukraine has the world's

In 2019, 82% of Ukrainians were Christians; out of which 72.7% declared themselves to be

Health

This section needs to be updated. (March 2022) |

Ukraine's healthcare system is state subsidised and freely available to all Ukrainian citizens and registered residents. However, it is not compulsory to be treated in a state-run hospital as a number of private medical complexes do exist nationwide.[328] The public sector employs most healthcare professionals, with those working for private medical centres typically also retaining their state employment as they are mandated to provide care at public health facilities on a regular basis.[329]

All of Ukraine's medical service providers and hospitals are subordinate to the

Ukraine faces a number of major public health issues[

Active reformation of Ukraine's healthcare system was initiated right after the appointment of

Education

According to the Ukrainian constitution, access to free education is granted to all citizens. Complete general secondary education is compulsory in the state schools which constitute the overwhelming majority. Free higher education in state and communal educational establishments is provided on a competitive basis.[336]

Because of the Soviet Union's emphasis on total access of education for all citizens, which continues today, the

Among the oldest is also the

The Ukrainian higher education system comprises higher educational establishments,

Ukraine produces the fourth largest number of

Regional differences

On the Russian language, on Soviet Union and Ukrainian nationalism, opinion in Eastern Ukraine and Southern Ukraine tends to be the exact opposite of those in Western Ukraine; while opinions in Central Ukraine on these topics tend be less extreme.[345][347][348][349]

Similar historical divisions also remain evident at the level of individual social identification. Attitudes toward the most important political issue, relations with Russia, differed strongly between

However, all were united by an overarching Ukrainian identity based on shared economic difficulties, showing that other attitudes are determined more by culture and politics than by demographic differences.[350][351] Surveys of regional identities in Ukraine have shown that the feeling of belonging to a "Soviet identity" is strongest in the Donbas (about 40%) and the Crimea (about 30%).[352]

During

Culture

Ukrainian customs are heavily influenced by Orthodox Christianity, the dominant religion in the country.[362] Gender roles also tend to be more traditional, and grandparents play a greater role in bringing up children, than in the West.[363] The culture of Ukraine has also been influenced by its eastern and western neighbours, reflected in its architecture, music and art.[364]

The Communist era had quite a strong effect on the art and writing of Ukraine.[365] In 1932, Stalin made socialist realism state policy in the Soviet Union when he promulgated the decree "On the Reconstruction of Literary and Art Organisations". This greatly stifled creativity. During the 1980s glasnost (openness) was introduced and Soviet artists and writers again became free to express themselves as they wanted.[366]

As of 2023[update], UNESCO inscribed 8 properties in Ukraine on the

The tradition of the Easter eggs, known as pysanky, has long roots in Ukraine. These eggs were drawn on with wax to create a pattern; then, the dye was applied to give the eggs their pleasant colours, the dye did not affect the previously wax-coated parts of the egg. After the entire egg was dyed, the wax was removed leaving only the colourful pattern. This tradition is thousands of years old, and precedes the arrival of Christianity to Ukraine.[373] In the city of Kolomyia near the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, the museum of Pysanka was built in 2000 and won a nomination as the monument of modern Ukraine in 2007, part of the Seven Wonders of Ukraine action.

Since 2012, the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine has formed the National Inventory of Elements of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Ukraine,[374] which consists of 92 items as of February 2024.[28]

Libraries

The Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, is the main academic library and main scientific information centre in Ukraine.

During the

Literature

Ukrainian literature has origins in

The Cossacks established an independent society and popularized a new kind of epic poem, which marked a high point of Ukrainian oral literature.[377][failed verification] These advances were then set back in the 17th and early 18th centuries, as many Ukrainian authors wrote in Russian or Polish. Nonetheless, by the late 18th century, the modern literary Ukrainian language finally emerged.[376] In 1798, the modern era of the Ukrainian literary tradition began with Ivan Kotliarevsky's publication of Eneida in the Ukrainian vernacular.[378]

By the 1830s, a Ukrainian romantic literature began to develop, and the nation's most renowned cultural figure, romanticist poet-painter Taras Shevchenko emerged. Whereas Ivan Kotliarevsky is considered to be the father of literature in the Ukrainian vernacular; Shevchenko is the father of a national revival.[379]

Then, in 1863, the use of the Ukrainian language in print was effectively

Ukrainian literature continued to flourish in the early Soviet years when nearly all literary trends were approved. These policies faced a steep decline in the 1930s, when prominent representatives as well as many others were killed by the NKVD during the Great Purge. In general around 223 writers were repressed by what was known as the Executed Renaissance.[380] These repressions were part of Stalin's implemented policy of socialist realism. The doctrine did not necessarily repress the use of the Ukrainian language, but it required that writers follow a certain style in their works.

Literary freedom grew in the late 1980s and early 1990s alongside the decline and collapse of the USSR and the reestablishment of Ukrainian independence in 1991.[376]

Architecture

Ukrainian architecture includes the motifs and styles that are found in structures built in modern Ukraine, and by

After the union with the

Weaving and embroidery

Artisan

National dress is woven and highly decorated. Weaving with handmade looms is still practised in the village of Krupove, situated in Rivne Oblast. The village is the birthplace of two internationally recognized personalities in the scene of national crafts fabrication: Nina Myhailivna[386] and Uliana Petrivna.[387]

Music

Music is a major part of Ukrainian culture, with a long history and many influences. From traditional folk music, to classical and modern rock, Ukraine has produced several internationally recognised musicians including Kirill Karabits, Okean Elzy and Ruslana. Elements from traditional Ukrainian folk music made their way into Western music and even into modern jazz. Ukrainian music sometimes presents a perplexing mix of exotic melismatic singing with chordal harmony. The most striking general characteristic of authentic ethnic Ukrainian folk music is the wide use of minor modes or keys which incorporate augmented second intervals.[389]

During the Baroque period, music had a place of considerable importance in the curriculum of the

The first dedicated musical academy was set up in Hlukhiv in 1738 and students were taught to sing and play violin and bandura from manuscripts. As a result, many of the earliest composers and performers within the Russian empire were ethnically Ukrainian, having been born or educated in Hlukhiv or having been closely associated with this music school.[390] Ukrainian classical music differs considerably depending on whether the composer was of Ukrainian ethnicity living in Ukraine, a composer of non-Ukrainian ethnicity who was a citizen of Ukraine, or part of the Ukrainian diaspora.[391]

Since the mid-1960s, Western-influenced pop music has been growing in popularity in Ukraine. Folk singer and harmonium player

Media

The Ukrainian legal framework on media freedom is deemed "among the most progressive in eastern Europe", although implementation has been uneven.

On 10 March 2024, creators of a documentary film 20 Days in Mariupol were awarded with the Oscar in the category "Best Documentary Feature Film", the first Oscar in Ukraine's history.[397]

Sport

Ukraine greatly benefited from the Soviet emphasis on physical education. These policies left Ukraine with hundreds of stadia, swimming pools, gymnasia and many other athletic facilities.[398] The most popular sport is football. The top professional league is the Vyscha Liha ("premier league").

Many Ukrainians also played for the

Ukrainian

Sergey Bubka held the record in the Pole vault from 1993 to 2014; with great strength, speed and gymnastic abilities, he was voted the world's best athlete on several occasions.[402][403]

Cuisine

The traditional Ukrainian diet includes chicken, pork, beef, fish and mushrooms. Ukrainians also tend to eat a lot of potatoes; grains; and fresh, boiled or pickled vegetables. Popular traditional dishes

Ukrainians drink stewed fruit compote, juices, milk, ryazhanka, mineral water, tea and coffee, beer, wine and horilka.[407]

See also

Notes

- ^ /juːˈkreɪn/ ⓘ yoo-KRAYN; Ukrainian: Україна, romanized: Ukrayina, pronounced [ʊkrɐˈjinɐ] ⓘ

- ^ Ukraine also has a battlefront to its southeast with territory illegally annexed from it by Russia.

- ^ Partly controlled by the unrecognised breakaway state Transnistria.

- ^ The Ukrainian territories on the Sea of Azov have been occupied and annexed by Russia in 2022, but the annexation has been condemned by the international community.

- ^ ethnicUkrainians, from the Ukrainian SSR.

- POWdeaths.

- ^ Such writings were also the base for Russian and Belarusian literature.

References

- ^ "Law of Ukraine "On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language": The status of Ukrainian and minority languages". 20 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Population by ethnic nationality, 1 January, year". ukrcensus.gov.ua. Ukrainian Office of Statistics. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches, 22 April 2018, pp. 12, 13, 16, 31, archived(PDF) from the original on 26 April 2018

Sample of 2,018 respondents aged 18 years and over, interviewed 23–28 March 2018 in all regions of Ukraine except Crimea and the occupied territories of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. - ^ "Ukraine". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 23 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-981-334-203-3. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Ukraine)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Ukraine". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Net, Korrespondent (18 October 2011). Рішення Ради: Україна 30 жовтня перейде на зимовий час [Rada Decision: Ukraine will change to winter time on 30 October] (in Ukrainian). korrespondent.net. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Ukraine country profile". BBC News. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ a b Beliakova, Polina; Tecott Metz, Rachel (17 March 2023). "The Surprising Success of U.S. Military Aid to Ukraine". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Yahoo News. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine – Trade – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. 2 May 2023.

- ^ "What is wrong with the Ukrainian economy?". Atlantic Council. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine becomes world's third biggest grain exporter in 2011 – minister" (Press release). Black Sea Grain. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "World Trade Report 2013". World Trade Organization. 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Linguistic divides: Johnson: Is there a single Ukraine?". The Economist. 5 February 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine – Definition". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Why Did "The Ukraine" Become Just "Ukraine"?". www.mentalfloss.com. 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Ukraine or the Ukraine: Why do some country names have 'the'?". BBC News. 7 June 2012.

- ^ "The "the" is gone". The Ukrainian Weekly. 8 December 1991. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Adam Taylor (9 December 2013). "Why Ukraine Isn't 'The Ukraine,' And Why That Matters Now". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Washington Post. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (7 June 2012). "Ukraine or the Ukraine: Why do some country names have 'the'?". BBC News Magazine. BBC.

- ^ a b "Національний перелік елементів нематеріальної культурної спадщини України". mcip.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). 23 February 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (10 June 2015). "Nomadic herders left a strong genetic mark on Europeans and Asians". Science. AAAS.

- S2CID 268262450.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 21698105.

- ^ Jennifer Carpenter (20 June 2011). "Early human fossils unearthed in Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ "Mystery of the domestication of the horse solved: Competing theories reconciled". sciencedaily (sourced from the University of Cambridge). 7 May 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ISBN 9780765600622.

- ^ "What We Theorize – When and Where Did Domestication Occur". International Museum of the Horse. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Horsey-aeology, Binary Black Holes, Tracking Red Tides, Fish Re-evolution, Walk Like a Man, Fact or Fiction". Quirks and Quarks Podcast with Bob Macdonald. CBC Radio. 7 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Balter, Michael (13 February 2015). "Mysterious Indo-European homeland may have been in the steppes of Ukraine and Russia". Science.

- PMID 25731166.

- ^ "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Scythian: Ancient People". Online Britannica. 20 July 1998. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Khazar | Origin, History, Religion, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 May 2023.

- ISBN 9780802078209. Retrieved 16 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Belyaev, A. (13 September 2012). "Русь и варяги. Евразийский исторический взгляд". Центр Льва Гумилёва (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Kievan Rus". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6 ed.). 2001–2007. Archived from the original on 19 August 2000. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-606-23920-9p. 69

- ISBN 9780313349201.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-0842-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-82442-2pp. 117–118

- ^ CIA World Factbook. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ISBN 0-888-44202-5pp. 195–196

- ISBN 0-19-517726-6

- ^ "The Destruction of Kiev". University of Toronto's Research Repository. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- ^ "Roman Mstyslavych". encyclopediaofukraine.com.

- ISBN 9781527558816.

- ISBN 9780521450119.

- ^ "Genuezskiye kolonii v Odesskoy oblasti – Biznes-portal Izmaila" Генуэзские колонии в Одесской области – Бизнес-портал Измаила [Genoese colonies in the Odesa region – Izmail's business portal] (in Russian). 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ISBN 9780465050918.

- ^ Radio Lemberg. "A History of Ukraine. Episode 33. The Crimean Khanate and Its Permanent Invasions of Ukraine". radiolemberg.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ISSN 0022-2097.

- ISBN 978-0-93088800-8. Archived from the originalon 4 May 2017.

- ^ Subtelny, pp. 92–93

- ^ Krupnytsky B. and Zhukovsky A. "Zaporizhia, The". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Ukraine – The Cossacks". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Matsuki, Eizo (2009). "The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves" (PDF). econ.hit-u.ac.jp. Hitotsubashi University (Mediterranean Studies Group). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2013.

- ^ "Poland". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Subtelny, pp. 123–124

- ^ Okinshevych, Lev; Arkadii Zhukovsky (1989). "Hetman state". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Vol. 2.

- ^ ISBN 9781442640856.

- ISBN 9781935850045.

- ^ Makuch, Andrij; Zasenko, Oleksa Eliseyovich; Yerofeyev, Ivan Alekseyevich; Hajda, Lubomyr A.; Stebelsky, Ihor; Kryzhanivsky, Stepan Andriyovich (13 December 2023). "Ukraine under direct imperial Russian rule". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ S2CID 128680044.

- ^ "The First Ukrainian Political Program: Mykhailo Drahomanov's Introduction to Hromadaurl". www.ditext.com. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Shevchenko, Taras". encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- S2CID 128063569.

- ISBN 978-0-2280-1199-6.

- ^ "Industrial Revolution | Key Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "On the industrial history of Ukraine". European Route of Industrial Heritage. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- OCLC 252946784.

- ISBN 0-7146-5232-6 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 0-8020-8390-0 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-1-4422-5281-3 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-8390-6.

- OCLC 902410832.

- ^ "Ukraine – World War I and the struggle for independence". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 May 2023.

- ^ "The Famine of 1920–1924". The Norka – a German Colony in Russia. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Famine of 1921–3". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003)The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943, The Past and Present Society: Oxford University Press. p. 202

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2005). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 32–33, 152–162

- ^ Revyuk, Emil (8 July 1931). "Polish Atrocities in Ukraine". Svoboda Press – via Google Books.

- ISBN 9789042912984– via Google Books.

- ^ Subtelny, p. 380

- ISBN 0674403487.

- ^ Christopher Gilley, 'The "Change of Signposts" in the Ukrainian emigration: Mykhailo Hrushevskyi and the Foreign Delegation of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries', Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Vol. 54, 2006, No. 3, pp. 345–74

- ^ "Ukraine remembers famine horror". BBC News. 24 November 2007.

- S. G. Wheatcroft, "Stalin, Grain Stocks and the Famine of 1932–1933", Slavic Review, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 642–657 online in JSTOR; Michael Ellman. "Stalin and the Soviet famine of 1932–33 Revisited", Europe-Asia Studies, Volume 59, Issue 4 June 2007, pages 663–693.

- ^ Wilson, p. 17

- ^ Subtelny, p. 487

- ^ "Treaty of Peace with Romania : February 10, 1947". Avalon Project. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Roberts, p. 102

- ^ Boshyk, p. 89

- ^ a b "Ukraine – World War II and its aftermath". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ Berkhoff, Karel Cornelis (April 2004). Harvest of despair: life and death in Ukraine under Nazi rule. Harvard University Press. p. 164.

- ^ a b "World wars". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- ISBN 9781442609914 – via Google Books.

- ^ Vedeneev, Dmitry (7 March 2015). "Військово-польова жандармерія - спеціальний орган Української повстанської армії" [Military Field Gendarmerie - special body of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army]. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (24 February 2010). "A Fascist Hero in Democratic Kiev". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Motyka, Grzegorz (2002). "Polska reakcja na działania UPA – skala i przebieg akcji odwetowych" [Polish reaction to the actions of the UPA – the scale and course of retaliation]. In Motyka, Grzegorz; Libionka, Dariusz (eds.). Antypolska Akcja OUN-UPA, 1943–1944, Fakty i Interpretacje [Anti-Polish Action OUN-UPA, 1943–1944, Facts and Interpretations] (PDF). Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014.

- JSTOR 3600827.

- ^ Piotrowski pp. 352–354

- ^ Weiner pp. 127–237

- OCLC 1058866168.

- ^ "Losses of the Ukrainian Nation, p. 2". Peremoga.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 15 May 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Subtelny, p. 476

- ^ Magocsi, p. 635

- ^ "Ukrainian Insurgent Army". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- ^ Weinberg, p. 264

- ^ "Losses of the Ukrainian Nation". Peremoga.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). p. 1. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ a b Stanislav Kulchytskyi (1 October 2004). "Demohrafichni vtraty Ukrayiny v khkh stolitti" Демографічні втрати України в хх столітті [Demographic losses of Ukraine in the 20 century] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv, Ukraine: Dzerkalo Tyzhnia. Retrieved 20 January 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Smale, Alison (27 January 2014). "Shedding Light on a Vast Toll of Jews Killed Away From the Death Camps". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Losses of the Ukrainian Nation, p. 7". Peremoga.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 15 May 2005. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Overy, p. 518

- ^ a b Кривошеев Г. Ф., Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: потери вооруженных сил. Статистическое исследование (Krivosheev G. F., Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century: losses of the Armed Forces. A Statistical Study) (in Russian)

- ^ "Вихідні та святкові дні 2022 року в Україні/Holidays 2022 in Ukraine". Consulate General of Ukraine in New York (in Ukrainian). 29 December 2021. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: World War II and its aftermath". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Activities of the Member States – Ukraine". United Nations. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ "United Nations". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

Voting procedures and the veto power of permanent members of the Security Council were finalized at the Yalta Conference in 1945 when Roosevelt and Stalin agreed that the veto would not prevent discussions by the Security Council. Roosevelt agreed to General Assembly membership for Ukraine and Byelorussia while reserving the right, which was never exercised, to seek two more votes for the United States.

- ^ "United Nations". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

Voting procedures and the veto power of permanent members of the Security Council were finalized at the Yalta Conference in 1945 when Roosevelt and Stalin agreed that the veto would not prevent discussions by the Security Council. In April 1945, new U.S. President Truman agreed to General Assembly membership for Ukraine and Byelorussia while reserving the right, which was never exercised, to seek two more votes for the United States.

- ^ Malynovska, Olena (14 June 2006). "Migration and migration policy in Ukraine". Archived from the original on 23 September 2013.

- ^ "The Transfer of Crimea to Ukraine". International Committee for Crimea. July 2005. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-8153-4058-4.

- ^ "Ukraine – The last years of Stalin's rule". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ Magocsi, p. 644

- ^ Magocsi, 1996, p. 704

- ^ Remy, Johannes (1996). "'Sombre anniversary' of worst nuclear disaster in history – Chernobyl: 10th anniversary". UN Chronicle. Find articles. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- )

- ^ "Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 16 July 1990. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Resolution On Declaration of Independence of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 24 August 1991. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Nohlen & Stöver, p1985

- RadioFreeEurope. 8 December 2006. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Лащенко, Олександр (26 November 2020). ""Україні не потрібно виходити із СНД – вона ніколи не була і не є зараз членом цієї структури"". Радіо Свобода.

- ^ Solodkov, Artem (27 December 2021). "Период распада: последний декабрь Союза. 26 декабря 1991 года". РБК (in Russian). Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Shen, p. 41

- ^ a b c Sutela, Pekka. "The Underachiever: Ukraine's Economy Since 1991". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian GDP (PPP)". World Economic Outlook Database, October 2007. International Monetary Fund (IMF). Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- ^ "Can Ukraine Avert a Financial Meltdown?". World Bank. June 1998. Archived from the original on 12 July 2000. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Figliuoli, Lorenzo; Lissovolik, Bogdan (31 August 2002). "The IMF and Ukraine: What Really Happened". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 17 October 2002. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ "Дефолт 1998 года: 10 лет спустя". ukraine.segodnya.ua (in Russian). 11 July 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "The stable crisis. Ukraine's economy three years after the Euromaidan". OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "War to cause Ukraine economy to shrink nearly a third this year – EBRD report – Ukraine". ReliefWeb. 10 May 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Dickinson, Peter (19 June 2021). "Ukraine's choice: corruption or growth". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- JSTOR 1149308.

- S2CID 214438848.

- PMID 35466444.

- ^ "Impact of war on the dynamics of COVID-19 in Ukraine - Ukraine". reliefweb.int. 17 April 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ISSN 0261-3794.

- S2CID 157151441.

- ^ ""Хунта" и "террористы": война слов Москвы и Киева". BBC News Русская служба (in Russian). 25 April 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Putin accuses US of orchestrating 2014 'coup' in Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 22 June 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "The Maidan in 2014 is a coup d'etat: a review of Italian and German pro-Russian media". Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- S2CID 159414642.

- S2CID 210591255.

- S2CID 248838806.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Pablo; Kirk, Ashley. "A year of war: how Russian forces have been pushed back in Ukraine". the Guardian.

- ^ Lonas, Lexi (12 May 2022). "5 ways Russia has failed in its invasion". The Hill. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine Country Report". EU-LISTCO. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ a b "EU awards Ukraine and Moldova candidate status". BBC News. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Top Ukrainian officials quit in anti-corruption drive". BBC News. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine – Relief". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Mining – UkraineInvest". 8 May 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Nature, Preferred by. "Ukraine Timber Risk Profile". NEPCon – Preferred by Nature. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- S2CID 242588829. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine invasion: rapid overview of environmental issues". CEOBS. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- hdl:10986/24971.

- ^ "Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Environmental issues in Ukraine". Naturvernforbundet. 16 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Ten-Step plan to address environmental impact of war in Ukraine" PAX for Peace. 24 February 2023. Accessed 30 April 2023.

- ^ "One Year In, Russia's War on Ukraine Has Inflicted $51 Billion in Environmental Damage" e360.yale.edu. 22 February 2023. Accessed 30 April 2023.

- ^ "Ukrainians hope to rebuild greener country after Russia's war causes 'ecocide'". The Independent. 19 March 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "The Environmental Cost of the War in Ukraine". International Relations Review. 2 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Qazi, Shereena. "'An Ecocide': How the conflict in Ukraine is bombarding the environment". ‘An Ecocide’: How the conflict in Ukraine is bombarding the environment. Retrieved 7 June 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "One Year In, Russia's War on Ukraine Has Inflicted $51 Billion in Environmental Damage". Yale E360. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine". Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine – Climate". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- S2CID 230613418.

- S2CID 233801987.

- ^ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org.

- PMID 28608869.

- ^ eISSN 2071-1050.

- OCLC 1056440382.

- ^ "Welcome to State of The Environment in Ukraine". The Ministry for Environmental Protection and Nuclear Safety of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "The List of Wetlands of International Importance" (PDF). Ukraine. Ramsar Organization. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "National planning tool for the implementation of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands" (PDF). Ramsar organization. 2002. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Regions of Ukraine and their divisions". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Official Web-site (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 31 December 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1" (PDF). ukrstat.gov.ua. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2022.

- OCLC 1038616889.

- ^ a b "Ukraine celebrating 20th anniversary of Constitution". www.unian.info. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- Eurasia Daily Monitor(30 July 2011)

- ^ 1996: the year in review Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Ukrainian Weekly (29 December 1996)

- ^ "Ukraine's parliament backs changes to Constitution confirming Ukraine's path toward EU, NATO". www.unian.info. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "General Articles about Ukraine". Government Portal. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Official Web-site. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Constitution of Ukraine". Wikisource. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ISBN 9789663821757.

- OCLC 828424860.

- ^ "Ukraine's president declared martial law after Russia's attack. But what is it?". USA Today.

- ^ "Ukraine President Submits Bill Extending Martial Law Until Late April". NDTV.com. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian Parliament Extends Martial Law For 90 Days". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 22 May 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "WJP Rule of Law Index® 2018–2019". data.worldjusticeproject.org. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ Byrne, Peter (25 March 2010). "Prosecutors fail to solve biggest criminal cases". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Українські суди майже не виносять виправдувальних вироків". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Byrne, Peter (25 March 2010). "Jackpot". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ a b "Ukraine". United States Department of State. 4 November 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Interfax-Ukraine (15 December 2011). "Constitutional Court rules Russian, other languages can be used in Ukrainian courts – Dec. 15, 2011". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

"З подачі "Регіонів" Рада дозволила російську у судах". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 July 2023. - ^ "Російська мова стала офіційною в українських судах". for-ua.com.

- ^ Chivers, C. J. (17 January 2005). "How Top Spies in Ukraine Changed the Nation's Path". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- OCLC 40350408.

- OCLC 1387966.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine has no alternative to Euro-Atlantic integration – Ukraine has no alternative to Euro-Atlantic integration – Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. 23 December 2014.

"Ukraine abolishes its non-aligned status – law". Interfax-Ukraine. 23 December 2014.

"Ukraine's complicated path to NATO membership". Euronews. 23 December 2014.

"Ukraine Takes Step Toward Joining NATO". The New York Times. 23 December 2014.

"Ukraine Ends 'Nonaligned' Status, Earning Quick Rebuke From Russia". The Wall Street Journal. 23 December 2014. - ^ "Teixeira: Ukraine's EU integration suspended, association agreement unlikely to be signed". Interfax. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ "EU, Ukraine to sign remaining part of Association Agreement on June 27 – European Council". Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ "EU-Ukraine Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area" (PDF). European Union. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "The EU-Ukraine Association Agreement and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area" (PDF). European Union. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Patricolo, Claudia (29 July 2018). "Ukraine looks to revive V4 membership hopes as Slovakia takes over presidency". Emerging Europe. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine Inaugurate 'Lublin Triangle'". Jamestown.

- ^ "Україна, Грузія та Молдова створили новий формат співпраці для спільного руху в ЄС". www.eurointegration.com.ua.

- ^ "У 2024 році Україна подасть заявку на вступ до ЄС". www.ukrinform.ua. 29 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Ukraine International Airlines launches direct Kyiv–New York flights". KyivPost. 6 June 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ Kelly, Mary Louise; Lonsdorf, Kat (21 February 2022). "Why Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons – and what that means in an invasion by Russia". NPR.org. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ a b "White Book 2006" (PDF). Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ Walters, Alex (24 February 2022). "In numbers: How does Ukraine's military stack up against Russia?". Forces Network.

- ^ "Ukrainian Navy Warship Hetman Sagaidachniy Joins EU Naval Force Counter Piracy Operation Atalanta". Eunavfor.eu. 6 January 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Multinational Peacekeeping Forces in Kosovo, KFOR". Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Peacekeeping". Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ^ "Kyiv Post. Independence. Community. Trust – Politics – Parliament approves admission of military units of foreign states to Ukraine for exercises". 22 May 2010. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010.

- ^ Collins, Liam (8 March 2022). "In 2014, the 'decrepit' Ukrainian army hit the refresh button. Eight years later, it's paying off". The Conversation. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Al Jazeera Staff. "What's in the new US military aid package to Ukraine?". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Is an outright Russian military victory in Ukraine possible?". The Guardian. 17 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "The council reduced the number of districts in Ukraine: 136 instead of 490". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 17 July 2020.

- ^ Bohdan Ben (25 September 2020). "Why Is Ukraine Poor? Look To The Culture Of Poverty". VoxUkraine. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "CPI 2023 for Eastern Europe & Central Asia: Autocracy & weak justice…". Transparency.org. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2021". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Ukraine economy could shrink by up to 35% in 2022, says IMF". The Guardian. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ Jaroslav Romanchuk (29 December 2021). "Ukrainian Economy in 2021: Procrastination Without Innovation". Get the Latest Ukraine News Today – Kyivpost. Kyiv Post. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) – Ukraine | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (national estimate) – Ukraine | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Lyubomyr Shavalyuk (10 October 2019). "Where Ukraine's middle class is and how it can develop". The Ukrainian Week. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Ukraine Government Debt: % of GDP". CEIC. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine's economy is more than just wheat and commodities | DW | 15 March 2022". DW.COM. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Statistics of Launches of Ukrainian LV". www.nkau.gov.ua. State Space Agency of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ^ "Missile defence, NATO: Ukraine's tough call". Business Ukraine. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ "Ukraine Special Weapons". The Nuclear Information Project. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ OCLC 1291390883.

- ^ "FAO Information Note: The importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for global agricultural markets and the risks associated with the current conflict, 25 March 2022 Update" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization.

- ^ "LDCs at a Glance | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "FAO Country Profiles". www.fao.org. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ISSN 1728-9246. Archived from the original(PDF) on 19 August 2008.

- ^ Ash, Lucy (8 August 2014). "Tourism takes a nosedive in Crimea". BBC News. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Судоходная компания Укрферри. Морские паромные перевозки на Черном Море между Украиной, Грузией, Турцией и Болгарией". Ukrferry.com. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "Киевскую дамбу может разрушить только метеорит или война — Эксперт". www.segodnya.ua. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine – Resources and power | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ^ "Transportation in Ukraine". U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "UIA Contacts". FlyUIA. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Liu, Jim (29 November 2017). "Ukraine International plans Toronto launch in June 2018". Routesonline. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ "The paradox threatening Ukraine's post-coal future". openDemocracy. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine – Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Fossil-Fuel Subsidies in the EU's Eastern Partner Countries : Estimates and Recent Policy Developments". OECD. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Westinghouse and Ukraine's Energoatom Extend Long-term Nuclear Fuel Contract". 11 April 2014. Westinghouse. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Kira (26 February 2022). "Ukraine's energy system coping but risks major damage as war continues". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine plans to end Russian gas transit contract in 2024 – interview for Deutsche Welle | Naftogaz Ukraine". www.naftogaz.com. 24 October 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine joins European power grid, ending its dependence on Russia". CBS News. No. 16 March 2022. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ENTSO-E. 16 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Could Russia shut down the internet in Ukraine?". The Guardian. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Davies, Pascale (11 March 2022). "Ukraine's tech companies are finding ways to help those fleeing war". euronews. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Archived from the originalon 3 April 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "Life expectancy and Healthy life expectancy, data by country". World Health Organization. 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Peterson, Nolan (26 February 2017). "Why Is Ukraine's Population Shrinking?". Newsweek. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Population". State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Koreans of Ukraine. Who are they?". Ukrainer. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Alina Sandulyak (18 July 2017). "Phantom Syndrome: Ethnic Koreans in Ukraine". Bird In Flight. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ "Ukraine - World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Caught Between East and West, Ukraine Struggles with Its Migration Policy". Migration Policy Institute. January 2006.

- ^ "National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons – March 2020 – Ukraine". ReliefWeb. 21 January 2021.

- ^ Hatoum, Bassam; Keaten, Jamey (30 March 2022). "Number of Ukraine refugees passes worst-case U.N. estimate". Associated Press. Medyka. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- ^ Armitage, Susie (8 April 2022). "'Ukrainian has become a symbol': interest in language spikes amid Russia invasion". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

Like most Ukrainians, Sophia Reshetniak, 20, is fluent in both Ukrainian and Russian.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3.

- ^ "Yanukovych signs language bill into law". Kyivpost.com. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Russian spreads like wildfires in dry Ukrainian forest". Kyivpost.com. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Romanian becomes regional language in Bila Tserkva in Zakarpattia region". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Michael Schwirtz (5 July 2012). "Ukraine". The New York Times.

- ^ Проект Закону про визнання таким, що втратив чинність, Закону України "Про засади державної мовної політики" [Draft Law on the recognition of the void Law of Ukraine "On the basic principles of State Language Policy"] (in Ukrainian). Ukrainian Parliament. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Ian Traynor (24 February 2014). "Western nations scramble to contain fallout from Ukraine crisis". The Guardian.

- ^ Andrew Kramer (2 March 2014). "Ukraine Turns to Its Oligarchs for Political Help". New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Constitutional Court Declares Law On Language Policy Unconstitutional". ukranews.com. 28 February 2018.

- ^ "New Language Requirement Raises Concerns in Ukraine". Human Rights Watch. 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Language data for Ukraine". Translators without Borders. March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Hungary plays ethnic card in all neighboring countries: experts explain "language row" with Ukraine". Unian. 7 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-349-57703-3. Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ISBN 0802035663.

- ^ Shamshur, pp. 159–168

- ^ "Світова преса про вибори в Україні-2004 (Ukrainian Elections-2004 as mirrored in the World Press)". Архіви України (National Archives of Ukraine). Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "Criticism of Ukraine's language law justified: rights body". Reuters. 7 December 2017.

- ^ "New language law could kill independent media ahead of 2019 elections". Kyiv Post. 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Ukrainian Language Bill Facing Barrage Of Criticism From Minorities, Foreign Capitals". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 24 September 2017.

- ^ "Ukraine defends education reform as Hungary promises 'pain'". The Irish Times. 27 September 2017.

- ^ Vic Satzewich, The Ukrainian Diaspora (Routledge, 2003).

- ^ Cecco, Leyland (3 March 2022). "In Canada, world's second largest Ukrainian diaspora grieves invasion". the Guardian. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ "How many refugees have fled Ukraine and where are they going?". BBC News. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "'Lot of determination': Ukrainian Americans rally for their country". The Guardian. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian refugees are now living in the UK - so how is it going?". BBC News. 28 May 2022.

- ^ "Hosts of Ukrainians in UK to receive government praise for generosity". 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Canada has opened its doors for war-ravaged Ukrainians. Does it have the capacity? - National | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ UNHCR (11 March 2022). "UNHCR scales up for those displaced by war in Ukraine, deploys cash assistance". Unhcr.

- ^ "Kyiv Saint Sophia Cathedral". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). UN. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Press releases and reports – Religious self-identification of the population and attitude to the main Churches of Ukraine: June 2021 (kiis.com.ua)".

- Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches, 26 May 2016, pp. 22, 27, archived from the original(PDF) on 22 April 2017, retrieved 7 January 2019

- ^ "ПРЕС-РЕЛІЗ ЗА РЕЗУЛЬТАТАМИ СОЦІОЛОГІЧНОГО ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ «УКРАЇНА НАПЕРЕДОДНІ ПРЕЗИДЕНТСЬКИХ ВИБОРІВ 2019»". socis.kiev.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches (sample of 2,018 people), 26 May 2016, pp. 22, 29, archived from the original(PDF) on 22 April 2017, retrieved 7 January 2019

- ^ "Medical Care in Ukraine. Health system, hospitals and clinics". BestOfUkraine.com. 1 May 2010. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- PMID 30470237.

- ^ Ukraine. "Health in Ukraine. Healthcare system of Ukraine". Europe-cities.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "'We are dying out here': Study hears Ukrainian voices on depopulation crisis". Phys.org. 27 April 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "What Went Wrong with Foreign Advice in Ukraine?". The World Bank Group. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ "What do you need to know about the healthcare reform in Ukraine?". UNIAN. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Ministry of Health: Medical institutions will receive guidance on how to convert to enterprises". Ukraine Crisis Media Center. 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "What do you need to know about the healthcare reform in Ukraine?". Ukraine Crisis Media Center. 11 September 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Constitution of Ukraine, Chapter 2, Article 53. Adopted at the Fifth Session of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine on 28 June 1996". Archived from the original on 15 April 1997.

- ^ "General secondary education". Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ "Higher education in Ukraine; Monographs on higher education; 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "System of Higher Education of Ukraine". Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ "System of the Education of Ukraine". Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ "export.gov". www.export.gov.

- ^ "Міносвіти скасує "спеціалістів" і "кандидатів наук"". life.pravda.com.ua. 11 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ISBN 9789280534320.

- ^ The Educational System of Ukraine, National Academic Recognition Information Centre, April 2009, archived from the original on 12 July 2020, retrieved 7 March 2013

- ^ Rating. 25 May 2012.

- ^ "Poll: Ukrainian language prevails at home", Ukrinform, UA, 7 September 2011, archived from the original on 9 July 2017, retrieved 7 January 2019

- Timothy Snyder (21 September 2010). "Who's Afraid of Ukrainian History?". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ "Poll: Over half of Ukrainians against granting official status to Russian language". Kyiv Post. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ Ставлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна [Attitude of the Ukrainian population to the figure of Joseph Stalin] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. 1 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Ukraine. West-East: Unity in Diversity". Research & Branding Group. March 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- S2CID 154250784

- ^ Taras Kuzio (23 August 2011). "Soviet conspiracy theories and political culture in Ukraine: Understanding Viktor Yanukovych and the Party of Region" (PDF). taraskuzio.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2014.

- ^ Вибори народних депутатів України 2012 [The Elections of People's Deputies of Ukraine 2012] (in Ukrainian). Central Election Commission of Ukraine. 28 November 2012. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ "CEC substitutes Tymoshenko, Lutsenko in voting papers". 30 August 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8

- openDemocracy.net, 3 January 2011, archived from the originalon 14 October 2017, retrieved 8 March 2013

- The Jamestown Foundation

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (5 October 2007), UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again (PDF), Oxford Analytica, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2013

- ^ Sonia, Koshkina (15 November 2012). "Ukraine's Party of Regions: A pyrrhic victory". EurActiv.

- ^ Rachkevych, Mark (11 February 2010). "Election winner lacks strong voter mandate". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Ostaptschuk, Markian (30 October 2012). "Shake-up in Ukraine". DW. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "State Department of Ukraine on Religious". 2003 Statistical report. Archived from the original on 4 December 2004. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- ISBN 978-1483405759.

- ^ "Culture in Ukraine | By Ukraine Channel". ukraine.com. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Interwar Soviet Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

In all, some four-fifths of the Ukrainian cultural elite was repressed or perished in the course of the 1930s

- ^ "Gorbachev, Mikhail". Encyclopædia Britannica (fee required). Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

Under his new policy of glasnost ("openness"), a major cultural thaw took place: freedoms of expression and of information were significantly expanded; the press and broadcasting were allowed unprecedented candour in their reportage and criticism; and the country's legacy of Stalinist totalitarian rule was eventually completely repudiated by the government

- ^ "UNESCO – Petrykivka decorative painting as a phenomenon of the Ukrainian ornamental folk art". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "UNESCO – Tradition of Kosiv painted ceramics". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "UNESCO – Cossack's songs of Dnipropetrovsk Region". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Ukraine – UNESCO World Heritage Convention". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Damaged cultural sites in Ukraine verified by UNESCO". UNESCO. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Unesco adds Ukrainian city of Odesa to World Heritage List of endangered sites". The Art Newspaper – International art news and events. 2 February 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Pysanky – Ukrainian Easter Eggs". University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2008.