Science

| Part of a series on |

| Science |

|---|

| This is a subseries on philosophy. In order to explore related topics, please visit navigation. |

Science is a strict

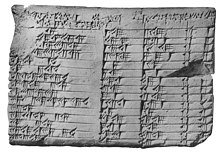

The history of science spans the majority of the historical record, with the earliest written records of identifiable predecessors to modern science dating to Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia from around 3000 to 1200 BCE. Their contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine entered and shaped the Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes, while further advancements, including the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, were made during the Golden Age of India.[15]: 12 [16][17][18] Scientific research deteriorated in these regions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire during the Early Middle Ages (400 to 1000 CE), but in the Medieval renaissances (Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century) scholarship flourished again. Some Greek manuscripts lost in Western Europe were preserved and expanded upon in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[19] along with the later efforts of Byzantine Greek scholars who brought Greek manuscripts from the dying Byzantine Empire to Western Europe at the start of the Renaissance.

The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived "natural philosophy",[20][21][22] which was later transformed by the Scientific Revolution that began in the 16th century[23] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[24][25] The scientific method soon played a greater role in knowledge creation and it was not until the 19th century that many of the institutional and professional features of science began to take shape,[26][27] along with the changing of "natural philosophy" to "natural science".[28]

New knowledge in science is advanced by research from scientists who are motivated by curiosity about the world and a desire to solve problems.[29][30] Contemporary scientific research is highly collaborative and is usually done by teams in academic and research institutions,[31] government agencies, and companies.[32][33] The practical impact of their work has led to the emergence of science policies that seek to influence the scientific enterprise by prioritizing the ethical and moral development of commercial products, armaments, health care, public infrastructure, and environmental protection.

Etymology

The word science has been used in

There are many hypotheses for science's ultimate word origin. According to Michiel de Vaan, Dutch linguist and Indo-Europeanist, sciō may have its origin in the Proto-Italic language as *skije- or *skijo- meaning "to know", which may originate from Proto-Indo-European language as *skh1-ie, *skh1-io, meaning "to incise". The Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben proposed sciō is a back-formation of nescīre, meaning "to not know, be unfamiliar with", which may derive from Proto-Indo-European *sekH- in Latin secāre, or *skh2-, from *sḱʰeh2(i)- meaning "to cut".[35]

In the past, science was a synonym for "knowledge" or "study", in keeping with its Latin origin. A person who conducted scientific research was called a "natural philosopher" or "man of science".[36] In 1834, William Whewell introduced the term scientist in a review of Mary Somerville's book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences,[37] crediting it to "some ingenious gentleman" (possibly himself).[38]

History

Early history

Science has no single origin. Rather, systematic methods emerged gradually over the course of tens of thousands of years,[39][40] taking different forms around the world, and few details are known about the very earliest developments. Women likely played a central role in prehistoric science,[41] as did religious rituals.[42] Some scholars use the term "protoscience" to label activities in the past that resemble modern science in some but not all features;[43][44][45] however, this label has also been criticized as denigrating,[46] or too suggestive of presentism, thinking about those activities only in relation to modern categories.[47]

Direct evidence for scientific processes becomes clearer with the advent of

The ancient

Classical antiquity

In

The early

A turning point in the history of early philosophical science was Socrates' example of applying philosophy to the study of human matters, including human nature, the nature of political communities, and human knowledge itself. The Socratic method as documented by Plato's dialogues is a dialectic method of hypothesis elimination: better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. The Socratic method searches for general commonly-held truths that shape beliefs and scrutinizes them for consistency.[66] Socrates criticized the older type of study of physics as too purely speculative and lacking in self-criticism.[67]

Positional notation for representing numbers likely emerged between the 3rd and 5th centuries CE along Indian trade routes. This numeral system made efficient arithmetic operations more accessible and would eventually become standard for mathematics worldwide.[76]

Middle Ages

Due to the

During

The

By the eleventh century, most of Europe had become Christian,[15]: 204 and in 1088, the University of Bologna emerged as the first university in Europe.[88] As such, demand for Latin translation of ancient and scientific texts grew,[15]: 204 a major contributor to the Renaissance of the 12th century. Renaissance scholasticism in western Europe flourished, with experiments done by observing, describing, and classifying subjects in nature.[89] In the 13th century, medical teachers and students at Bologna began opening human bodies, leading to the first anatomy textbook based on human dissection by Mondino de Luzzi.[90]

Renaissance

New developments in optics played a role in the inception of the

In the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus formulated a heliocentric model of the Solar System, stating that the planets revolve around the Sun, instead of the geocentric model where the planets and the Sun revolve around the Earth. This was based on a theorem that the orbital periods of the planets are longer as their orbs are farther from the center of motion, which he found not to agree with Ptolemy's model.[92]

The

Age of Enlightenment

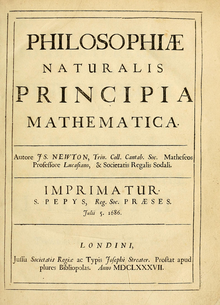

At the start of the Age of Enlightenment, Isaac Newton formed the foundation of classical mechanics by his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, greatly influencing future physicists.[99] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz incorporated terms from Aristotelian physics, now used in a new non-teleological way. This implied a shift in the view of objects: objects were now considered as having no innate goals. Leibniz assumed that different types of things all work according to the same general laws of nature, with no special formal or final causes.[100]

During this time, the declared purpose and value of science became producing wealth and inventions that would improve human lives, in the materialistic sense of having more food, clothing, and other things. In Bacon's words, "the real and legitimate goal of sciences is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches", and he discouraged scientists from pursuing intangible philosophical or spiritual ideas, which he believed contributed little to human happiness beyond "the fume of subtle, sublime or pleasing [speculation]".[101]

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by

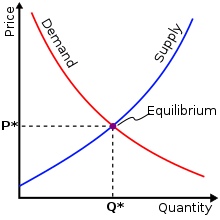

The 18th century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine[106] and physics;[107] the development of biological taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus;[108] a new understanding of magnetism and electricity;[109] and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline.[110] Ideas on human nature, society, and economics evolved during the Enlightenment. Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed A Treatise of Human Nature, which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity.[111] Modern sociology largely originated from this movement.[112] In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, which is often considered the first work on modern economics.[113]

19th century

During the nineteenth century, many distinguishing characteristics of contemporary modern science began to take shape. These included the transformation of the life and physical sciences; the frequent use of precision instruments; the emergence of terms such as "biologist", "physicist", and "scientist"; an increased professionalization of those studying nature; scientists gaining cultural authority over many dimensions of society; the industrialization of numerous countries; the thriving of popular science writings; and the emergence of science journals.[114] During the late 19th century, psychology emerged as a separate discipline from philosophy when Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory for psychological research in 1879.[115]

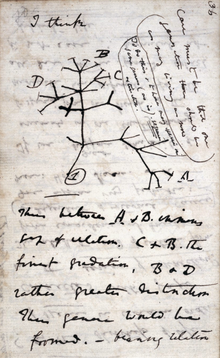

During the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1858, which explained how different plants and animals originated and evolved. Their theory was set out in detail in Darwin's book On the Origin of Species, published in 1859.[116] Separately, Gregor Mendel presented his paper, "Experiments on Plant Hybridization" in 1865,[117] which outlined the principles of biological inheritance, serving as the basis for modern genetics.[118]

Early in the 19th century,

The

20th century

In the first half of the century, the development of

During this period, scientific experimentation became increasingly larger in scale and funding.[129] The extensive technological innovation stimulated by World War I, World War II, and the Cold War led to competitions between global powers, such as the Space Race and nuclear arms race.[130][131] Substantial international collaborations were also made, despite armed conflicts.[132]

In the late 20th century, active recruitment of women and elimination of

The century saw fundamental changes within science disciplines. Evolution became a unified theory in the early 20th-century when the modern synthesis reconciled Darwinian evolution with classical genetics.[136] Albert Einstein's theory of relativity and the development of quantum mechanics complement classical mechanics to describe physics in extreme length, time and gravity.[137][138] Widespread use of integrated circuits in the last quarter of the 20th century combined with communications satellites led to a revolution in information technology and the rise of the global internet and mobile computing, including smartphones. The need for mass systematization of long, intertwined causal chains and large amounts of data led to the rise of the fields of systems theory and computer-assisted scientific modeling.[139]

21st century

The Human Genome Project was completed in 2003 by identifying and mapping all of the genes of the human genome.[140] The first induced pluripotent human stem cells were made in 2006, allowing adult cells to be transformed into stem cells and turn to any cell type found in the body.[141] With the affirmation of the Higgs boson discovery in 2013, the last particle predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics was found.[142] In 2015, gravitational waves, predicted by general relativity a century before, were first observed.[143][144] In 2019, the international collaboration Event Horizon Telescope presented the first direct image of a black hole's accretion disk.[145]

Branches

Modern science is commonly divided into three major

Natural science

Natural science is the study of the physical world. It can be divided into two main branches: life science and physical science. These two branches may be further divided into more specialized disciplines. For example, physical science can be subdivided into physics, chemistry, astronomy, and earth science. Modern natural science is the successor to the natural philosophy that began in Ancient Greece. Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, and Newton debated the benefits of using approaches which were more mathematical and more experimental in a methodical way. Still, philosophical perspectives, conjectures, and presuppositions, often overlooked, remain necessary in natural science.[149] Systematic data collection, including discovery science, succeeded natural history, which emerged in the 16th century by describing and classifying plants, animals, minerals, and so on.[150] Today, "natural history" suggests observational descriptions aimed at popular audiences.[151]

Social science

Social science is the study of human behavior and functioning of societies.[4][5] It has many disciplines that include, but are not limited to anthropology, economics, history, human geography, political science, psychology, and sociology.[4] In the social sciences, there are many competing theoretical perspectives, many of which are extended through competing research programs such as the functionalists, conflict theorists, and interactionists in sociology.[4] Due to the limitations of conducting controlled experiments involving large groups of individuals or complex situations, social scientists may adopt other research methods such as the historical method, case studies, and cross-cultural studies. Moreover, if quantitative information is available, social scientists may rely on statistical approaches to better understand social relationships and processes.[4]

Formal science

Applied science

Computational science applies computing power to simulate real-world situations, enabling a better understanding of scientific problems than formal mathematics alone can achieve. The use of machine learning and artificial intelligence is becoming a central feature of computational contributions to science for example in agent-based computational economics, random forests, topic modeling and various forms of prediction. However, machines alone rarely advance knowledge as they require human guidance and capacity to reason; and they can introduce bias against certain social groups or sometimes underperform against humans.[171][172]

Interdisciplinary science

Interdisciplinary science involves the combination of two or more disciplines into one,[173] such as bioinformatics, a combination of biology and computer science[174] or cognitive sciences. The concept has existed since the ancient Greek and it became popular again in the 20th century.[175]

Scientific research

Scientific research can be labeled as either basic or applied research.

Scientific method

Scientific research involves using the

In the scientific method, an explanatory

When a hypothesis proves unsatisfactory, it is modified or discarded.

While performing experiments to test hypotheses, scientists may have a preference for one outcome over another.[185][186] Eliminating the bias can be achieved by transparency, careful experimental design, and a thorough peer review process of the experimental results and conclusions.[187][188] After the results of an experiment are announced or published, it is normal practice for independent researchers to double-check how the research was performed, and to follow up by performing similar experiments to determine how dependable the results might be.[189] Taken in its entirety, the scientific method allows for highly creative problem solving while minimizing the effects of subjective and confirmation bias.[190] Intersubjective verifiability, the ability to reach a consensus and reproduce results, is fundamental to the creation of all scientific knowledge.[191]

Scientific literature

Scientific research is published in a range of literature.[192] Scientific journals communicate and document the results of research carried out in universities and various other research institutions, serving as an archival record of science. The first scientific journals, Journal des sçavans followed by Philosophical Transactions, began publication in 1665. Since that time the total number of active periodicals has steadily increased. In 1981, one estimate for the number of scientific and technical journals in publication was 11,500.[193]

Most scientific journals cover a single scientific field and publish the research within that field; the research is normally expressed in the form of a

Challenges

The

An area of study or speculation that masquerades as science in an attempt to claim a legitimacy that it would not otherwise be able to achieve is sometimes referred to as

There can also be an element of political or ideological bias on all sides of scientific debates. Sometimes, research may be characterized as "bad science," research that may be well-intended but is incorrect, obsolete, incomplete, or over-simplified expositions of scientific ideas. The term "scientific misconduct" refers to situations such as where researchers have intentionally misrepresented their published data or have purposely given credit for a discovery to the wrong person.[202]

Philosophy of science

There are different schools of thought in the

Empiricism has stood in contrast to

Another approach, instrumentalism, emphasizes the utility of theories as instruments for explaining and predicting phenomena. It views scientific theories as black boxes with only their input (initial conditions) and output (predictions) being relevant. Consequences, theoretical entities, and logical structure are claimed to be something that should be ignored.[209] Close to instrumentalism is constructive empiricism, according to which the main criterion for the success of a scientific theory is whether what it says about observable entities is true.[210]

Finally, another approach often cited in debates of

Scientific community

The scientific community is a network of interacting scientists who conducts scientific research. The community consists of smaller groups working in scientific fields. By having peer review, through discussion and debate within journals and conferences, scientists maintain the quality of research methodology and objectivity when interpreting results.[215]

Scientists

Scientists are individuals who conduct scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of interest.

Scientists exhibit a strong curiosity about reality and a desire to apply scientific knowledge for the benefit of health, nations, the environment, or industries. Other motivations include recognition by their peers and prestige. In modern times, many scientists have

Science has historically been a male-dominated field, with notable exceptions. Women in science faced considerable discrimination in science, much as they did in other areas of male-dominated societies. For example, women were frequently being passed over for job opportunities and denied credit for their work.[225] The achievements of women in science have been attributed to the defiance of their traditional role as laborers within the domestic sphere.[226]

Learned societies

The professionalization of science, begun in the 19th century, was partly enabled by the creation of national distinguished

Awards

Science awards are usually given to individuals or organizations that have made significant contributions to a discipline. They are often given by prestigious institutions, thus it is considered a great honor for a scientist receiving them. Since the early Renaissance, scientists are often awarded medals, money, and titles. The Nobel Prize, a widely regarded prestigious award, is awarded annually to those who have achieved scientific advances in the fields of medicine, physics, and chemistry.[238]

Society

Funding and policies

Scientific research is often funded through a competitive process in which potential research projects are evaluated and only the most promising receive funding. Such processes, which are run by government, corporations, or foundations, allocate scarce funds. Total research funding in most developed countries is between 1.5% and 3% of GDP.[239] In the OECD, around two-thirds of research and development in scientific and technical fields is carried out by industry, and 20% and 10% respectively by universities and government. The government funding proportion in certain fields is higher, and it dominates research in social science and humanities. In the lesser-developed nations, government provides the bulk of the funds for their basic scientific research.[240]

Many governments have dedicated agencies to support scientific research, such as the

Education and awareness

The mass media face pressures that can prevent them from accurately depicting competing scientific claims in terms of their credibility within the scientific community as a whole. Determining how much weight to give different sides in a

Science magazines such as New Scientist, Science & Vie, and Scientific American cater to the needs of a much wider readership and provide a non-technical summary of popular areas of research, including notable discoveries and advances in certain fields of research.[253] Science fiction genre, primarily speculative fiction, can transmit the ideas and methods of science to the general public.[254] Recent efforts to intensify or develop links between science and non-scientific disciplines, such as literature or poetry, include the Creative Writing Science resource developed through the Royal Literary Fund.[255]

Anti-science attitudes

While the scientific method is broadly accepted in the scientific community, some fractions of society reject certain scientific positions or are skeptical about science. Examples are the common notion that COVID-19 is not a major health threat to the US (held by 39% of Americans in August 2021)[256] or the belief that climate change is not a major threat to the US (also held by 40% of Americans, in late 2019 and early 2020).[257] Psychologists have pointed to four factors driving rejection of scientific results:[258]

- Scientific authorities are sometimes seen as inexpert, untrustworthy, or biased.

- Some social groups hold anti-science attitudes, in part because these groups have often been exploited in unethical experiments.[259]

- Messages from scientists may contradict deeply-held existing beliefs or morals.

- The delivery of a scientific message may not be appropriately targeted to a recipient's learning style.

Anti-science attitudes seem to be often caused by fear of rejection in social groups. For instance, climate change is perceived as a threat by only 22% of Americans on the right side of the political spectrum, but by 85% on the left.[260] That is, if someone on the left would not consider climate change as a threat, this person may face contempt and be rejected in that social group. In fact, people may rather deny a scientifically accepted fact than lose or jeopardize their social status.[261]

Politics

See also

Notes

- ^ Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics Book I, [6.54]. pages 372 and 408 disputed Claudius Ptolemy's extramission theory of vision; "Hence, the extramission of [visual] rays is superfluous and useless". —A.Mark Smith's translation of the Latin version of Ibn al-Haytham.[84]: Book I, [6.54]. pp. 372, 408

- ^ Whether the universe is closed or open, or the shape of the universe, is an open question. The 2nd law of thermodynamics,[120]: 9 [121] and the 3rd law of thermodynamics[122] imply the heat death of the universe if the universe is a closed system, but not necessarily for an expanding universe.

References

- ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0.

...modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-367-56298-4. Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Colander, David C.; Hunt, Elgin F. (2019). "Social science and its methods". Social Science: An Introduction to the Study of Society (17th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 1–22.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Robert A.; Greenfeld, Liah (16 October 2020). "Social Science". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ S2CID 9272212.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-19138-6. Archivedfrom the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7923-1270-3. Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ a b Nickles, Thomas (2013). "The Problem of Demarcation". Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 104.

- ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4438-1946-6.

- PMID 24872859.

- ^ Sinclair, Marius (1993). "On the Differences between the Engineering and Scientific Methods". The International Journal of Engineering Education. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ S2CID 110332727.

- ^ ISBN 978-0226482057.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- ^ Building Bridges Among the BRICs Archived April 18, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p. 125, Robert Crane, Springer, 2014

- ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

The great era of all that is deemed classical in Indian literature, art and science was now dawning. It was this crescendo of creativity and scholarship, as much as ... political achievements of the Guptas, which would make their age so golden.

- ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Sease, Virginia; Schmidt-Brabant, Manfrid. Thinkers, Saints, Heretics: Spiritual Paths of the Middle Ages. 2007. Pages 80-81. Retrieved October 6, 2023

- ISBN 978-0-19-956741-6.

- ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- ISBN 978-0-226-08928-7.

- ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ISBN 978-0-226-18451-7.

The changing character of those engaged in scientific endeavors was matched by a new nomenclature for their endeavors. The most conspicuous marker of this change was the replacement of "natural philosophy" by "natural science". In 1800 few had spoken of the "natural sciences" but by 1880, this expression had overtaken the traditional label "natural philosophy". The persistence of "natural philosophy" in the twentieth century is owing largely to historical references to a past practice (see figure 11). As should now be apparent, this was not simply the substitution of one term by another, but involved the jettisoning of a range of personal qualities relating to the conduct of philosophy and the living of the philosophical life.

- ISBN 978-1-4398-6965-9. Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-521-14584-8. Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-138-57016-0. Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ISBN 978-1-138-40741-1. Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "science". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ISBN 978-90-04-16797-1.

- from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- .

- ^ "scientist". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ISBN 978-0-521-81229-0.

- PMID 28489015.

- ^ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (2021). The Dawn of Everything. p. 248.

- JSTOR 124782.

- ISBN 978-94-010-8181-8.

- S2CID 43643053.

- S2CID 253597172.

- OCLC 700406626.

- S2CID 141599452.

- ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ISBN 978-0313324338.

- ISBN 978-1-55587-672-2. Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

The Nile occupied an important position in Egyptian culture; it influenced the development of mathematics, geography, and the calendar; Egyptian geometry advanced due to the practice of land measurement "because the overflow of the Nile caused the boundary of each person's land to disappear."

- ^ "Telling Time in Ancient Egypt". The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57607-966-9. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- S2CID 122508567.

- ^ Biggs, R D. (2005). "Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19 (1): 7–18.

- ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023. The word φύσις, while first used in connection with a plant in Homer, occurs early in Greek philosophy, and in several senses. Generally, these senses match rather well the current senses in which the English word nature is used, as confirmed by Guthrie, W.K.C. Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus (volume 2 of his History of Greek Philosophy), Cambridge UP, 1965.

- ISBN 978-0814319024. Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-0533-1. Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1. Archivedfrom the original on 29 January 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-08-101107-2. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Lucretius (fl. 1st c. BCE) De rerum natura

- Golden Press. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7. Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Leff, Samuel; Leff, Vera (1956). From Witchcraft to World Health. London, England: Macmillan. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Plato, Apology". p. 17. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Plato, Apology". p. 27. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics (H. Rackham ed.). 1139b. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4214-1776-9. Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-4612-8788-9. Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-3-658-18682-1. Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-387-94313-8. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-539-1. Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-19-926288-5. Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-139-48453-4. Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- OCLC 62164511.

- ISBN 978-0-521-56762-6. Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Wildberg, Christian (1 May 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2018 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Falcon, Andrea (2019). "Aristotle on Causality". In Zalta, Edward (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-521-68957-1.

- OCLC 745412.

- ^ "Bayt al-Hikmah". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-0415259347.

- ^ OCLC 47168716.

- JSTOR 228328. See p. 464: "Schramm sums up [Ibn Al-Haytham's] achievement in the development of scientific method.", p. 465: "Schramm has demonstrated .. beyond any dispute that Ibn al-Haytham is a major figure in the Islamic scientific tradition, particularly in the creation of experimental techniques." p. 465: "only when the influence of Ibn al-Haytham and others on the mainstream of later medieval physical writings has been seriously investigated can Schramm's claim that Ibn al-Haytham was the true founder of modern physics be evaluated."

- ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- .

Perhaps even as early as 1088 (the date officially set for the founding of the University)

- ^ "St. Albertus Magnus | German theologian, scientist, and philosopher". Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-674-03327-6. Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ S2CID 27806323.

- S2CID 118351058. Archived from the original(PDF) on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4.

- ISBN 0-14-019246-8.

- ^ van Helden, Al (1995). "Pope Urban VIII". The Galileo Project. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-691-00966-7.

- Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- ISBN 978-0-7139-9503-9.

Although it was just one of the many factors in the Enlightenment, the success of Newtonian physics in providing a mathematical description of an ordered world clearly played a big part in the flowering of this movement in the eighteenth century

- ^ "Gottfried Leibniz – Biography". Maths History. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-9604-4. Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ISBN 978-0816013159.

- ISBN 978-0511819421. Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ "The Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment (1500–1780)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Scientific Revolution | Definition, History, Scientists, Inventions, & Facts". Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-0131443297.

- ISBN 978-0521640664.

- PMID 17436393.

- ISBN 0198505949.

- ^ Olby, R.C.; Cantor, G.N.; Christie, J.R.R.; Hodge, M.J.S. (1990). Companion to the History of Modern Science. London: Routledge. p. 265.

- ^ Magnusson, Magnus (10 November 2003). "Review of James Buchan, Capital of the Mind: how Edinburgh Changed the World". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- JSTOR 588406.

- ISBN 978-0-415-06164-3.

- ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ISBN 978-1-138-65242-2.

- PMID 18256649.

- ^ Henig, Robin Marantz (2000). The monk in the garden: the lost and found genius of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics. pp. 134–138.

- ^ Miko, Ilona (2008). "Gregor Mendel's principles of inheritance form the cornerstone of modern genetics. So just what are they?". Nature Education. 1 (1): 134. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- S2CID 141350239.

- ^ ISBN 0-7131-2789-9.

- ISBN 978-81-7371-048-3.

- from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-7503-0224-1.

- ^ Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4(in Polish). p. 113.

- from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Goyotte, Dolores (2017). "The Surgical Legacy of World War II. Part II: The age of antibiotics" (PDF). The Surgical Technologist. 109: 257–264. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- S2CID 94880859. Archived from the originalon 23 July 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- doi:10.5282/rcc/6313. Archived from the originalon 21 January 2022.

- S2CID 34844169.

- ISBN 0-525-94571-7.

- ^ Kahn, Herman (1962). Thinking about the Unthinkable. Horizon Press.

- from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8147-7645-2.

- (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5.

- ISBN 978-1605356051. Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-201-04679-3.

- ISBN 978-0-08-012101-7.

- JSTOR 255139.

- PMID 22155605.

- PMID 23131523.

- ^ O'Luanaigh, C. (14 March 2013). "New results indicate that new particle is a Higgs boson" (Press release). CERN. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- S2CID 217162243.

- .

- ^ "Media Advisory: First Results from the Event Horizon Telescope to be Presented on April 10th | Event Horizon Telescope". 20 April 2019. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "Scientific Method: Relationships Among Scientific Paradigms". Seed Magazine. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ^ OCLC 59377149.

- ISBN 978-0-521-01708-4. Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-226-62088-6.

- ^ "Natural History". Princeton University WordNet. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Formal Sciences: Washington and Lee University". Washington and Lee University. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

A "formal science" is an area of study that uses formal systems to generate knowledge such as in Mathematics and Computer Science. Formal sciences are important subjects because all of quantitative science depends on them.

- ^ "formal system". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Tomalin, Marcus (2006). Linguistics and the Formal Sciences.

- S2CID 9272212.

- ^ Bill, Thompson (2007). "2.4 Formal Science and Applied Mathematics". The Nature of Statistical Evidence. Lecture Notes in Statistics. Vol. 189. Springer. p. 15.

- ISBN 978-0-7658-0413-6.

- ISBN 978-3-319-27494-2.

- ^ "About the Journal". Journal of Mathematical Physics. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-19-049459-9. Archived from the originalon 10 June 2021.

- ^ "What is mathematical biology". Centre for Mathematical Biology, University of Bath. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Tim (1 September 2009). "What is financial mathematics?". +Plus Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Varian, Hal (1997). "What Use Is Economic Theory?". In D'Autume, A.; Cartelier, J. (eds.). Is Economics Becoming a Hard Science?. Edward Elgar. Pre-publication. Archived June 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- S2CID 21610124.

- ^ "Cambridge Dictionary". Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-19-874669-0.

- S2CID 73306806.

- PMID 10704471.

- PMID 19790950.

- from the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- JSTOR 23767672.

- ISBN 978-0-471-32788-2.

- ^ Ausburg, Tanya (2006). Becoming Interdisciplinary: An Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies (2nd ed.). New York: Kendall/Hunt Publishing.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (10 May 2006). "To Live at All Is Miracle Enough". RichardDawkins.net. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-29925-1.

The amazing point is that for the first time since the discovery of mathematics, a method has been introduced, the results of which have an intersubjective value!

- OCLC 59377149.

- ISBN 978-0199543182.

- ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8.

- ISBN 978-0-19-922689-4.

- JSTOR 2246135.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-3769-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-3769-6.

- ^ van Gelder, Tim (1999). ""Heads I win, tails you lose": A Foray Into the Psychology of Philosophy" (PDF). University of Melbourne. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ Pease, Craig (6 September 2006). "Chapter 23. Deliberate bias: Conflict creates bad science". Science for Business, Law and Journalism. Vermont Law School. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010.

- OCLC 54989960.

- OCLC 185926306.

- OCLC 47791316.

- ^ Backer, Patricia Ryaby (29 October 2004). "What is the scientific method?". San Jose State University. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-521-22087-3.

- PMID 7367863.

- OCLC 232950234.

- ^ a b Bush, Vannevar (July 1945). "Science the Endless Frontier". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- PMID 25373639.

- S2CID 26361121.

- PMID 26431313.

- ^ Hansson, Sven Ove; Zalta, Edward N. (3 September 2008). "Science and Pseudoscience". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Section 2: The "science" of pseudoscience. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-7167-3090-3.

- ^ Feynman, Richard (1974). "Cargo Cult Science". Center for Theoretical Neuroscience. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2005. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-1473696419.

- ^ "Coping with fraud" (PDF). The COPE Report 1999: 11–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

It is 10 years, to the month, since Stephen Lock ... Reproduced with kind permission of the Editor, The Lancet.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Popper, Karl (1972). Objective Knowledge.

- ISBN 978-0-7100-0913-5.

- ^ Votsis, I. (2004). The Epistemological Status of Scientific Theories: An Investigation of the Structural Realist Account (PhD Thesis). University of London, London School of Economics. p. 39.

- ^ Bird, Alexander (2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Thomas Kuhn". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-226-45804-5. Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-226-30062-7.

- ^ Brugger, E. Christian (2004). "Casebeer, William D. Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition". The Review of Metaphysics. 58 (2).

- (PDF) from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Eusocial climbers" (PDF). E.O. Wilson Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

But he's not a scientist, he's never done scientific research. My definition of a scientist is that you can complete the following sentence: 'he or she has shown that...'," Wilson says.

- ^ "Our definition of a scientist". Science Council. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

A scientist is someone who systematically gathers and uses research and evidence, making a hypothesis and testing it, to gain and share understanding and knowledge.

- PMID 21512548.

- .

- .

- .

- PMID 21512548.

- .

- .

- ^ Whaley, Leigh Ann (2003). Women's History as Scientists. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, INC.

- ISBN 978-0-253-20968-9.

- ^ Parrott, Jim (9 August 2007). "Chronicle for Societies Founded from 1323 to 1599". Scholarly Societies Project. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- ^ "The Environmental Studies Association of Canada – What is a Learned Society?". Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Learned societies & academies". Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Learned Societies, the key to realising an open access future?". Impact of Social Sciences. London School of Economics. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei" (in Italian). 2006. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- ^ "Prince of Wales opens Royal Society's refurbished building". The Royal Society. 7 July 2004. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- ^ Meynell, G.G. "The French Academy of Sciences, 1666–91: A reassessment of the French Académie royale des sciences under Colbert (1666–83) and Louvois (1683–91)". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ ITS. "Founding of the National Academy of Sciences". .nationalacademies.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "The founding of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (1911)". Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Introduction". Chinese Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Two main Science Councils merge to address complex global challenges". UNESCO. 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ Stockton, Nick (7 October 2014). "How did the Nobel Prize become the biggest award on Earth?". Wired. Archived from the original on 19 June 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "Main Science and Technology Indicators – 2008-1" (PDF). OECD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010.

- ISBN 978-9264239784. Archivedfrom the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022 – via oecd-ilibrary.org.

- S2CID 32956693.

- ^ "Argentina, National Scientific and Technological Research Council (CONICET)". International Science Council. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Le CNRS recherche 10.000 passionnés du blob". Le Figaro (in French). 20 October 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "En espera de una "revolucionaria" noticia sobre Sagitario A*, el agujero negro supermasivo en el corazón de nuestra galaxia". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). 12 May 2022. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- PMID 23028299.

- OCLC 875999943.

- (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ Dickson, David (11 October 2004). "Science journalism must keep a critical edge". Science and Development Network. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010.

- ^ Mooney, Chris (November–December 2004). "Blinded By Science, How 'Balanced' Coverage Lets the Scientific Fringe Hijack Reality". Columbia Journalism Review. Vol. 43, no. 4. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^ McIlwaine, S.; Nguyen, D.A. (2005). "Are Journalism Students Equipped to Write About Science?". Australian Studies in Journalism. 14: 41–60. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- PMID 24312943.

- ^ Wilde, Fran (21 January 2016). "How Do You Like Your Science Fiction? Ten Authors Weigh In On 'Hard' vs. 'Soft' SF". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Petrucci, Mario. "Creative Writing – Science". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Tyson, Alec; Funk, Cary; Kennedy, Brian; Johnson, Courtney (15 September 2021). "Majority in U.S. Says Public Health Benefits of COVID-19 Restrictions Worth the Costs, Even as Large Shares Also See Downsides". Pew Research Center Science & Society. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Brian (16 April 2020). "U.S. concern about climate change is rising, but mainly among Democrats". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- PMID 35858405.

- S2CID 144645723.

- ^ Poushter, Jacob; Fagan, Moira; Gubbala, Sneha (31 August 2022). "Climate Change Remains Top Global Threat Across 19-Country Survey". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- OCLC 1322437138. Archivedfrom the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (26 October 2021). "Revealed: 60% of Americans say oil firms are to blame for the climate crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021.

Source: Guardian/Vice/CCN/YouGov poll. Note: ±4% margin of error.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeanne (2017). "The Politicization of Scientific Issues: Looking through Galileo's Lens or through the Imaginary Looking Glass". Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (5): 34–39. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Druckman, James N.(2015). "Counteracting the Politicization of Science". Journal of Communication (65): 746.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2019.