Violence in art

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Depictions of violence in

History in art

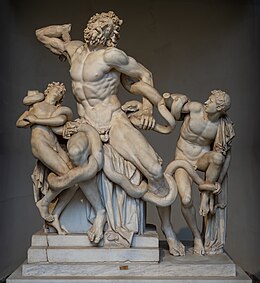

Antiquity

This section may contain information not important or relevant to the article's subject. (July 2022) |

15th century to 17th century

Politics of House of Medici and Florence dominate art depicted in Piazza della Signoria, making references to first three Florentine dukes. Besides aesthetical depiction of violence these sculptures are noted for weaving through a political narrative.[3]

The artist

18th century onwards

In the mid-18th century, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, an Italian etcher, archaeologist, and architect active from 1740, did imaginary etchings of prisons that depicted people "stretched on racks or trapped like rats in maze-like dungeons", an "aestheticization of violence and suffering".[5]

In 1849, as revolutions raged in European streets and authorities were putting down protests and consolidating state powers, composer Richard Wagner wrote: "I have an enormous desire to practice a little artistic terrorism."[6]

In high culture

Everything in this world has two handles. Murder, for instance, may be laid hold of by its moral handle... and that, I confess, is its weak side; or it may also be treated aesthetically, as the Germans call it—that is, in relation to good taste.[7]

In his 1991 study of romantic literature, University of Georgia literature professor Joel Black stated that "(if) any human act evokes the aesthetic experience of the sublime, certainly it is the act of murder". Black notes that "...if murder can be experienced aesthetically, the murderer can in turn be regarded as a kind of artist—a performance artist or anti-artist whose specialty is not creation but destruction."[8]

In films

Film critics analyzing violent film images that seek to aesthetically please the viewer mainly fall into two categories. Critics who see depictions of violence in film as superficial and exploitative argue that such films lead audience members to become desensitized to brutality, thus increasing their aggression. On the other hand, critics who view violence as a type of content, or as a theme, claim it is cathartic and provides "acceptable outlets for anti-social impulses".

Margaret Bruder, a film studies professor at Indiana University and the author of Aestheticizing Violence, or How to Do Things with Style, proposes that there is a distinction between aestheticized violence and the use of gore and blood in mass market action or war films. She argues that "aestheticized violence is not merely the excessive use of violence in a film". Movies such as the popular action film Die Hard 2 are very violent, but they do not qualify as examples of aestheticized violence because they are not "stylistically excessive in a significant and sustained way".[1] Bruder argues that films such as such as Hard Target, True Romance and Tombstone employ aestheticized violence as a stylistic tool. In such films, "the stylized violence they contain ultimately serves as (...) another interruption in the narrative drive".[1]

A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 film written, directed, and produced by Stanley Kubrick and based on the novel of the same name by Anthony Burgess. Set in a futuristic England (circa 1995, as imagined in 1965), it follows the life of a teenage gang leader named Alex. In Alexander Cohen's analysis of Kubrick's film, he argues that the ultra-violence of the young protagonist, Alex, "...represents the breakdown of culture itself". In the film, gang members are "...[s]eeking idle de-contextualized violence as entertainment" as an escape from the emptiness of their dystopian society. When the protagonist murders a woman in her home, Cohen states that Kubrick presents a "[s]cene of aestheticized death" by setting the murder in a room filled with "...modern art which depict scenes of sexual intensity and bondage"; as such, the scene depicts a "...struggle between high-culture which has aestheticized violence and sex into a form of autonomous art, and the very image of post-modern mastery".[10]

Writing in

In Xavier Morales' review of Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill: Volume 1, he calls the film "a groundbreaking aestheticization of violence".[12] Morales argues that, similarly to A Clockwork Orange, the film's use of aestheticized violence appeals to audiences as an aesthetic element, and thus subverts preconceptions of what is acceptable or entertaining.[12]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Bruder, Margaret Ervin (1998). "Aestheticizing Violence, or How To Do Things with Style". Film Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington IN. Archived from the original on 2004-09-08. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ISSN 1095-5054. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^ Mandel, C. "Perseus and the Medici." Storia Dell'Arte no. 87 (1996): 168

- ^ Alsford, Stephen (2004-02-29). "Death – Introductory essay". Florilegium Urbanum. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^ "db artmag". Deutsche Bank Art. 2005. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^ a b Dworkin, Craig (2006-01-17). "Trotsky's Hammer" (PDF). Salt Lake City, UT: Department of English, University of Utah. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-26. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ISBN 1-84749-133-2. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ISBN 0801841801. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- ISSN 1443-4059. Archived from the original(Archive) on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^ Cohen, Alexander J. (1998). "Clockwork Orange and the Aestheticization of Violence". UC Berkeley Program in Film Studies. Archived from the original on 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (2016-03-24). "In Hindsight, an 'American Psycho' Looks a Lot Like Us". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ^ a b Morales, Xavier (2003-10-16). "Beauty and violence". The Record. Harvard Law School RECORD Corporation. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

Further reading

- Berkowitz, L. (ed) (1977; 1986): Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vols 10 & 19. New York: Academic Press

- Bersani, Leo and Ulysse Dutoit, The Forms of Violence: Narrative in Assyrian Art and Modern Culture (NY: Schocken Books, 1985)

- Black, Joel (1991) The Aesthetics of Murder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Feshbach, S. (1955): The Drive-Reducing Function of Fantasy Behaviour, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 50: 3–11

- Feshbach, S & Singer, R. D. (1971): Television and Aggression: An Experimental Field Study. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kelly, George. (1955) The Psychology of Personal Constructs. Vol. I, II. Norton, New York. (2nd printing: 1991, Routledge, London, New York)

- Peirce, Charles Sanders (1931–58): Collected Writings. (Edited by Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss, & Arthur W Burks). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.