Wenlock Christison

Wenlock Christison | |

|---|---|

| Born | before 1660 |

| Died | c. 1679 |

| Occupation(s) | Missionary, Farmer[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Mary unknown,[1] Elizabeth Gary[1] |

| Children | Mary Dine,[1] Elizabeth Christison[1] John Christison |

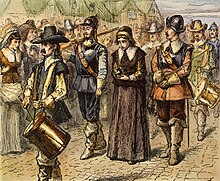

Wenlock Christison (before 1660 – c. 1679) was the last person to be sentenced to death in the

Persecution in Boston

Wenlock's origins are unknown. Historians sometimes reported his last name as Christopherson. He may have been of Scottish descent, and referred to himself as a British subject. The earliest record of him is from 1660 when he was held in jail in

From Boston, Christison and Leddra went to Plymouth Colony, where they were robbed, whipped, imprisoned and eventually banished.[4] By this time William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevenson, two Quakers who had been banished from Massachusetts, had returned and were executed on 27 October 1659. Mary Dyer was executed on 1 April 1660 under the same circumstances.[5]

Seeking martyrdom, Christison and Leddra also returned to Boston. Leddra was arrested in late 1660 or early in 1661 while visiting some friends in prison. He was tried and hanged in March, 1661.

Quaker writer George Bishop wrote,

Yea, Wenlock Christison, though they did not put him to death, yet they sentenced him to die, so that their cruel purposes were nevertheless. I cannot forbear to mention what he spoke, being so prophetical, not only as to the judgment of God coming on Major-general Adderton, but as to their putting any more Quakers to death after they had passed sentence on him.

[9] Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recreated the Christison trial in his play John Endicott which included the damnation of Atherton by the accused.[10]

However, before the execution could take place, Charles II issued a royal mandate to the New England Colonies "granting full and free tolerance to all sects for the exercise of their religion and exempting Quakers from the punishment of death for any other offenses than those for which that penalty was adjudged by the laws of England."[11] In addition, public distaste for the executions emerged.[12] Christison was released from prison on 7 April 1661, after signing a written promise to leave Massachusetts and not to enter the colony again.[13]

The royal mandate did end the executions but not the persecutions. Over the following two years the mandate was modified. "Accordingly, we find the persecutions were renewed, and Quakers were arrested, fined, imprisoned and banished as before, but no one suffered death after the hanging of William Leddra."

Later life

In 1670, Wenlock Christison settled down on a 150-acre (61 ha) farm in Talbot County, Maryland. The property, named "Ending of Controversy", was given to him by a wealthy Quaker physician, Peter Sharpe. Sharpe had married Judith Gary, the widow of John Gary. Judith's son, John, was married to Alice Ambrose, who had been arrested with Christison in Massachusetts. Another of Sharpes' stepchildren, Eliazbeth Gary, would become Christison's wife after her first husband, Robert Harwood, died.[17] This was probably Christison's second marriage. He had children but it is not known how many. Christison acquired other property, including indentured servants and slaves.[18] He was elected to the lower house of the Maryland General Assembly,[19] mostly likely shortly before his death. He died about 1679.[17]

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recreated Christison's 1661 trial in John Endicott, one of three dramatic poems in a collection called New England Tragedies.[10]

References

- ^ a b c d e Papenfuse, Edward. A Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature 1635–1789 Vlo 426. Maryland: Maryland State Archives. p. 220.

- OL 7221177M.

- ^ "Nonviolence in American History". SNCC, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Papers, 1959–1972 (Sanford, NC: Microfilming Corporation of America, 1982) Reel 67, File 328, Page 0365 The original papers are at the King Library and Archives, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Harrison, pgs.20–22

- ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5. p. 536

- ^ Graves, Dan. "William Leddra: Executed for Quakerism". Salem Web Network. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Harrison, pgs. 23–31

- ^ Harrison pg.33

- ^ Bishop, George. New-England judged, by the spirit of the Lord. T. Sowle. 1703 pp. 306

- ^ a b Longfellow, Henry W. Poetical Works. G. Routledge and Sons. 1891. p. 498

- ^ Harrison pgs. 34–38

- ^ Fiske, John (1892). Dainial MacÀdhaimh (ed.). "Persecution of Quakers in Colonial New England". The Beginnings of New England (excerpted 2005). World Spirituality. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Harrison pg.38

- ^ Harrison pg.39

- ^ Harrison pgs. 40–47

- ^ Wroten, William. "Wenlock Christison-Man of Freedowm". Salisbury Times. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ a b Papenfuse, pg. 728, http://aomol.net/000001/000426/html/am426--728.html

- ^ Harrison pgs. 48–70

- ^ Hand, William (1889). Archives of Maryland. Maryland: Maryland Historical Society. p. 134.