Weywot

Quaoar and Weywot (left of Quaoar) imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2006 | |

| Discovery[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by |

|

| Discovery date | 14 February 2006 |

| Designations | |

Designation | (50000) Quaoar I[4]: 134 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈweɪwɒt/ |

| S/2006 (50000) 1[5] | |

| Orbital characteristics[6] | |

| Epoch 23 March 2008 (JD 2454549.42)[6] | |

| 13289±189 km (2023)[7] 13900±200 (2013)[6] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.056±0.093 (2023)[7] 0.137±0.006 (2013)[6] |

| 12.4311±0.0015 d (2023)[7] 12.4314±0.0002 d (2013)[6] | |

| Inclination | 15.8°±0.7° (to ecliptic) |

| 1.0°±0.7° | |

| 335°±0.7° | |

| Satellite of | 50000 Quaoar |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean diameter | ≈ 200 km[8] |

| Albedo | ≈ 0.04[8] |

| 24.7[9][a] | |

| ≈ 8.3[a] | |

Weywot (formal designation (50000) Quaoar I;

Discovery

Weywot was first imaged by the

To determine Weywot's orbit, Brown reobserved Weywot with Hubble in March 2007 and March 2008.[12][13][9] Together with his colleague Wesley Fraser, Brown published the first preliminary orbit of Weywot in May 2010. Fraser and Brown were unable to precover Weywot in earlier ultraviolet Hubble images of Quaoar from 2002, either because the satellite was obscured by Quaoar or it was too faint in ultraviolet light.[11]: 1548

Name

Upon discovery, Weywot was given a

Orbit

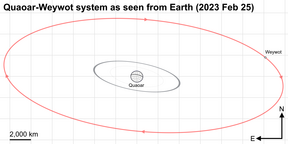

Weywot orbits Quaoar at an average distance of 13,300 km (8,300 mi) and takes 12.4 days to complete one revolution.[7]: 3 Its orbit is likely coplanar with Quaoar's equator,[15]: 1 while the entire Quaoar system is inclined by about 16° with respect to the ecliptic plane.[6]: 359

Weywot has a high

Prior to further observations in 2019,

Ring dynamics

In February 2023, astronomers announced the discovery of a distant

Physical characteristics

Weywot is extremely dim, with an

As of 2023[update], Weywot is thought to be about 200 km (120 mi) in diameter, based on multiple observations of a stellar occultation by Weywot on 22 June 2023.[8] Occultations by Weywot have been observed previously on 4 August 2019, 11 June 2022, and 26 May 2023, which all gave similar diameter estimates of about 170 km (110 mi).[17][18][8] Given Weywot's magnitude difference from Quaoar, this occultation-derived diameter suggests Weywot has low geometric albedo of about 0.04, considerably darker than Quaoar's albedo of 0.12.[8] Weywot was previously thought to have a diameter of 81 ± 11 km (50 ± 7 mi), about half that of the occultation measurement, because researchers based this estimate only on Weywot's relative brightness and assumed it had a similar albedo as Quaoar.[19]: 15 [11]: 1547 [8]

Notes

References

- ^ Bibcode:2007IAUC.8812....1B. Archivedfrom the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b Johnston, Wm. Robert (21 September 2014). "(50000) Quaoar and Weywot". Asteroids with Satellites Database. Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ Suer, Terry-Ann. "Publications". sites.google.com. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ a b "M. P. C. 67220" (PDF). Minor Planet Circulars (67220). Minor Planet Center: 134. 4 October 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 50000 Quaoar (2002 LM60)". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ S2CID 17196395.

- ^ Wikidata Q116754015.

- ^ a b c d e f Fernandez-Valenzuela, E.; Holler, B.; Ortiz, J. L.; Vachier, F.; Braga-Ribas, F.; Rommel, F.; et al. (October 2023). Weywot: the darkest known satellite in the trans-Neptunian region. 55th Annual DPS Meeting Joint with EPSC. Vol. 55. San Antonio, Texas. 202.04.

- ^ a b c d Grundy, Will (21 March 2022). "Quaoar and Weywot (50000 2002 LM60)". www2.lowell.edu. Lowell Observatory. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Bibcode:2005hst..prop10545B. Cycle 14. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ S2CID 17386407.

- Bibcode:2006hst..prop10860B. Cycle 15. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- Bibcode:2007hst..prop11169B. Cycle 16. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Street, Nick (August 2008). "Heavenly Bodies and the People of the Earth". Search Magazine. Heldref Publications. Archived from the original on 18 May 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Wikidata Q117802048.

- ^ S2CID 237213381. 226.

- Bibcode:2020JOA....10a..24K.

- ^ "2022 Asteroidal Occultation Preliminary Results – 50000(1) Weywot 2022 Jun 11". www.asteroidoccultation.com. International Occultation Timing Association. 11 June 2022. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023.

- .