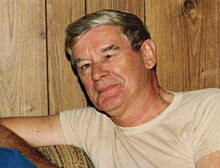

Wilson Tucker (writer)

Wilson Tucker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Arthur Wilson Tucker November 23, 1914 Deer Creek, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | October 6, 2006 (aged 91) St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S. |

| Pen name | Bob Tucker, Hoy Ping Pong |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 1932–2006 (as fan) |

| Genre | Science fiction, mystery |

| Notable works |

|

Arthur Wilson "Bob" Tucker (November 23, 1914 – October 6, 2006) was an American author who became well known as a writer of mystery, action adventure, and science fiction under the name Wilson Tucker.

Tucker was also a prominent member of

Life

Born in Deer Creek, Illinois, for most of his life Tucker made his home in Bloomington, Illinois. He was married twice. In 1937, he wed Mary Joesting; they had a son and a daughter before the marriage dissolved in 1942. His second marriage, to Fern Delores Brooks in 1953, lasted 52 years, until her death in 2006; they had three sons.

Fandom

Tucker became involved in science fiction fandom in 1932, publishing a fanzine, The Planetoid. From 1938 to 2001, he published the fanzine

He also published the Bloomington News Letter, which dealt with news within the professional science fiction writing field. Active in letter-writing as well, Tucker was a popular fan during more than six decades, coining many words and phrases familiar in science fiction fandom and to literary criticism of the field. In addition to "Bob Tucker", he was also known to write under the pseudonym "Hoy Ping Pong" (generally reserved for humorous pieces.)[2] During a 41-year period, 1955 to 1996, Tucker created and edited eight separate editions of The Neo-Fan's Guide To Science Fiction Fandom, an historical overview of the first five decades of science fiction fandom, with important events and trends in fandom noted. Each edition also carried a lexicon of fan terminology in use throughout fandom at the time. The eighth and final edition remains in print from the Kansas City Science Fiction and Fantasy Society.

Tucker's fanzine writing has been described as "unfailingly incisive", and Tucker as "the most intelligent and articulate and sophisticated fan the American science-fiction community is ever likely to boast of".[3] He helped pioneer criticism of the genre, coining along the way terms like "space opera" in common use today.[4]

He was fan guest of honor, professional guest of honor, toastmaster, or master of ceremonies at so many

In 1940, he served on the committee of the Worldcon in Chicago. In 2001, he co-hosted the joint Ditto/FanHistoriCon held in his hometown of Bloomington, Illinois.

Tucker won the

The

Tuckercon, the 2007 NASFiC (North American Science Fiction Convention) in Collinsville, Illinois, was dedicated to Tucker.

Career

Although he sold more than 20 novels, Tucker made his principal living as a movie

Professional writing

In 1941, Tucker's first professional short story, "Interstellar Way Station", was published by Frederik Pohl in the May issue of Super Science Stories. Between 1941 and 1979, primarily in the early 1940s and early 1950s, he produced about two dozen more.[7] He also turned his attention to writing novels, with 11 mystery novels and a dozen science fiction novels to his credit.

His most famous novel may be

Other notable novels include The Lincoln Hunters (1958), in which time-travelers from an oppressive future society seek to record Abraham Lincoln's "lost speech" of May 19, 1856. It contains a vivid description of Lincoln and his time, seen through the eyes of a future American who feels that Lincoln and his time compare very favorably with the traveler's own.

The Long Loud Silence (1952) is a post-apocalypse story in which the eastern third of the United States is quarantined as the result of an atomic and bacteriological attack. Damon Knight[8] called it "a phenomenally good book; in its own terms, it comes as near perfection as makes no difference."

Much of Tucker's short fiction was collected in The Best of Wilson Tucker (Timescape, 1982;

Tucker's habit of using the names of friends for minor characters in his fiction led to the literary term "tuckerization" or "tuckerism(s)".[9][10] For example, Tucker named a character after Lee Hoffman in his novel The Long Loud Silence, after Robert Bloch in The Lincoln Hunters, and after Walt Willis in Wild Talent.[11]

Selected works

Novels

- Charles Home mysteries (five, 1946 to 1951)

- The Chinese Doll (1946)

- The City in the Sea (1951)

- The Long Loud Silence (1952)

- The Time Masters (1953, revised 1971)

- Wild Talent (1954) (aka Man from Tomorrow, 1955 )

- Time: X (1955)

- Time Bomb (1955) (aka Tomorrow Plus X)

- The Lincoln Hunters (1958)

- To the Tombaugh Station (1960)

- A Procession of the Damned (1965)

- The Year of the Quiet Sun(1970)

- This Witch (1971)

- Ice and Iron (1974)

- Resurrection Days (1981)

Stories

- The Princess of Detroit, Future Science Fiction(June 1942)

- The Planet King (1959)

- The Best of Wilson Tucker (Timescape, 1982) (collection)

Nonfiction

- The Neo-Fan's Guide To Science Fiction Fandom (eight editions, 1955 to 1996)

See also

References

- ^ Katz, Arnie. "Philosophical Theory of Fanhistory" in Fan History Archive Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Robert Bloch. "Wilson Tucker – The Smo-o-oth Operator" in Bloch's Out of My Head, Cambridge MA: NESFA Press, 1986.

- ^ Clute, John "Wilson Tucker: Writer of bleak science fiction." The Independent 12 Oct. 2006

- ^ Browning, T.G. "Stanley G. Weinbaum: SF Flare". Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ^ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame". Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved March 26, 2013. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

- ^ Locus Publications. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Wilson Tucker at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Knight, Damon (1967). In Search of Wonder. Chicago: Advent.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530567-8.

- ^ Baen, Jim. "The Tucker Circle". Jim Baen's Universe. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ Langford, David. "Tuckerisms". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Gollancz. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

External links

- Wilson Tucker home page

- Wilson Bob Tucker – Author and Fan, with photo gallery of Tucker and page images of Tucker's fanzine Le Zombie

- Obituary by John Clute in The Independent

- Obituary at Science Fiction Writers of America

- Wilson Tucker at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "Wilson Tucker biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- Wilson Tucker at Library of Congress Authorities — with 25 catalog records