Principality of Catalonia

Principality of Catalonia Principat de Catalunya ( Latin) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12th century – 1714/1833 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

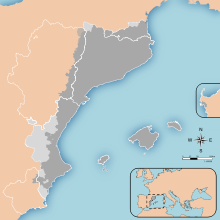

Territory of the Principality of Catalonia until 1659. Location superimposed to current borders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

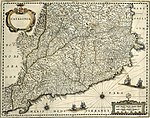

Location of the Principality of Catalonia (light green, at the left) within the Crown of Aragon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Barcelona | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy subject to constitutions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Count[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1164–1196 | Alfons I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1706–1714 | Charles III (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

President of the Deputation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1359–1362 | Berenguer de Cruïlles (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1713–1714 | Josep de Vilamala (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Catalan Courts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval / Early modern | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Reign of Alfons I | 1164–1196 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• First legal definition of Catalonia | 1173 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• First Catalan constitutions | 1283 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1359 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Reign of Charles I | 1516–1556 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1659 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1701–1714 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1700 | c. 500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Croat, Ducat, Florin, Peseta, and others | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Principality of Catalonia (

The first reference to

Its institutional system evolved over the centuries, establishing political bodies analogous to the ones of the other kingdoms of the Crown (such as the Courts, the

The marriage of

History

Origins

Like much of the Mediterranean coast of the

The

A distinctive Catalan culture started to develop in the

In 988 Count

Under count

Dynastic union

In 1137 Count

His son, King Peter II of Aragon, faced the defense of the Occitan territories, acquired from the times of Ramon Berenguer I onwards, from the Albigensian Crusade. The Battle of Muret (12 September 1213) and the unexpected defeat of King Peter and his vassals and allies, the counts of Toulouse, Comminges and Foix, against the French-Crusader armies, resulted in the fading of the strong human, cultural and economic ties existing between the ancient territories of Catalonia and the Languedoc.[26]

In the

As a coastal territory within the Crown of Aragon and with the increasing importance of the port of Barcelona, Catalonia became the main centre of the Crown's maritime power, promoting and helping to expand its influence and power by conquest and trade into Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia and Sicily.

Catalan constitutions (1283–1716) and the 15th century

At the same time, the Principality of Catalonia developed a complex institutional and political system based on the concept of pact between the estates of the realm and the monarch. The laws (called constitutions) had to be approved in the General Court of Catalonia,

The General Court of Catalonia (or Catalan Courts), with roots dating from the 11th century, is one of the first parliamentary bodies of Europe that, since 1283, obtained the power to create legislation with the monarch. The Courts were composed of the three Estates organized in to "arms" (braços), were presided over by the monarch as count of Barcelona.[31][32] The current Parliament of Catalonia is considered the symbolic and historic successor of this institution.[33]

In order to recapt the "tax of the General", the Courts of 1359 established a permanent representation of deputies, called Deputation of the General (in Catalan: Diputació del General) and later usually known as

The Principality saw a prosperous period during the 13th century and the first half of the 14th. The population increased; Catalan language and culture expanded into the islands of the Western Mediterranean. The reign of

This territorial expansion was accompanied by a great development of the Catalan trade, centered in Barcelona, creating an extensive trade network across the Mediterranean which competed with those of the

The second quarter of the 14th century saw crucial changes for Catalonia, marked by a succession of natural catastrophes, demographic crises, stagnation and decline in the Catalan economy, and the rise of social tensions. The year 1333 was known as Lo mal any primer (Catalan: "The first bad year") due to poor wheat harvest.[42] The domains of the Aragonese Crown were affected severely by the Black Death pandemic and by later outbreaks of the plague. Between 1347 and 1497 Catalonia lost 37 percent of its population.[43]

In 1410, King Martin I, the last reigning monarch of the House of Barcelona, died without surviving descendants. Under the Compromise of Caspe (1412), Ferdinand from the Castilian House of Trastámara received the Crown of Aragon as Ferdinand I of Aragon.[44] Ferdinand's successor, Alfonso V ("the Magnanimous"), promoted a new stage of Catalan-Aragonese expansion, this time over the Kingdom of Naples, over which he eventually gained rule in 1443. However, he aggravated the social crisis in the Principality of Catalonia, both in the countryside and in the cities. Political conflict in Barcelona arose due to the disputes over the control of the Consell de Cent between two political factions, Biga and Busca looking for a solution to the economic crisis. Meanwhile, the remença (serfs') peasants subjected to the feudal abuses known as evil customs began to organize themselves as a syndicate against seignorial pressures, seeking protection from the monarch. Alfonso's brother, John II ("the Unreliable"), was a deeply hated regent and ruler, both in the Basque kingdom of Navarre and in Catalonia.

The opposition of the institutions of Catalonia to the policies of John II resulted in their support to the son of John, Charles, Prince of Viana over his denied dynastic rights. In response of the detention of Charles by his father, the Generalitat established a political body, the Council of the Principality, with whom, under menace of a conflict, John was forced to negotiate. The Capitulation of Vilafranca (1461) forced to release Charles from prison and appoint him lieutenant of Catalonia, while the king would need permission of the Generalitat to enter the Principality. The content of the Capitulation represented a culmination and consolidation of pactism and the constitutional system of Catalonia. However, the disagreement of King John, the death of Charles shortly after, and the Remença Uprising in 1462 led to the ten-year Catalan Civil War (1462-1472) that left the country exhausted. In 1472, the last separate ruler of Catalonia, King René of Anjou ("the Good"), lost the war against King John.

John's son,

Catalonia during the early modern period

The marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon (1469) unified two of the three major Christian kingdoms in the Iberian peninsula, while the Kingdom of Navarre was incorporated later following Ferdinand II's 1512 invasion of the Basque kingdom.

This resulted in the reinforcement of the concept of Spain, which was already present in the mind of these kings,

For an extended period, Catalonia, as part of the late

Over the next two centuries, Catalonia was generally on the losing side of a series of wars that led steadily to more centralization of power in Spain. Despite this fact, between the 16th and 18th centuries, the role of the political community in local affairs and the general government of the country was increased, while the royal powers remained relatively restricted, specially after the two last Courts (1701–1702 and 1705–1706). Tensions between the constitutional Catalan institutions and the gradually more centralized monarchy began to arise.

In 1659, after the

In the last decades of the 17th century during the reign of Spain's last Habsburg king,

At the dawn of the

After Nueva Planta

Apart from the abolition of the Catalan institutions, the Nueva Planta decrees ensured the imposition of the new absolutist system by reforming the Royal Audience of Catalonia, making it the highest governmental body of the Principality, absorbing many of the functions of the abolished institutions and becoming the instrument with which the

On several occasions during the first third of the 20th century, Catalonia gained and lost varying degrees of autonomy, recovering the administrative unity in 1914, when the four Catalan provinces were authorized to create a commonwealth (Catalan:

The

The term Principality

| History of Catalonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| 27 BC – 476 AD |