Abacus (architecture)

In

Definition

In

In the archaic Greek Ionic order, owing to the greater width of the capital, the abacus is rectangular in plan, and consists of a carved ovolo moulding. In later examples, the slab is thinner and the abacus remains square, except where there are angled volutes, where the slab is slightly curved. In the Roman and Renaissance Ionic capital, the abacus is square with a fillet on the top of an ogee moulding with curved edges over angled volutes.[2]

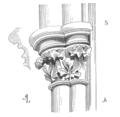

In an angular capital of the Greek Corinthian order, the abacus is moulded, its sides are concave, and its angles canted[3] (except in one or two exceptional Greek capitals, where it is brought to a sharp angle); the volutes of adjacent faces meet and project diagonally under each corner of the abacus. The same shape is adopted in the Roman and Renaissance Corinthian and Composite capitals, in some cases with the carved ovolo moulding, fillet, and cavetto.[2][4]

In

In Gothic architecture, the moulded forms of the abacus vary in shape, such as square, circular, or even octagonal,[5] it may even be a flat disk or drum.[2] The form of the Gothic abacus is often affected by the shape of a vault that springs from the column, in which case it is called an impost block.

Indian architecture (śilpaśāstra)

In śilpaśāstra, the ancient Indian science of sculpture, the abacus is commonly termed as phalaka (or phalakā).[6] It consists of a flat plate and forms part of the standard pillar (stambha). The phalaka should be constructed below the potikā ("bracket"). It is commonly found together with the dish-like maṇḍi as a single unit. The term is found in encyclopedic books such as the Mānasāra, Kāmikgāgama and the Suprabhedāgama.

Examples in England

Early

Examples in France

The first abacus pictured below (fig. 5) is decorated with simple mouldings and ornaments, common during the 12th century, in Île-de-France, Normandy, Champagne, and Burgundy regions, and from the choir of

-

Fig. 5

-

Fig. 6

-

Fig. 7

-

Fig. 8

Sources

- Wikisource has original text related to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition article: Abacus.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Brown 1993, p. 2

- ^ a b c d Cruickshank 1996, p. 1713

- ^ Avery 1962, p. 1

- ^ Kay 1955, p. 1

- ^ Lagassé 2000, p. 1

- ISBN 8170173124.

References

- Avery, Catherine A., ed. (1962). "abacus". The New Century Classical Handbook. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc. LCCN 62-10069.

- Brown, Lesley, ed. (1993). "abacus". Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Vol. 2: A-K (5th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860575-1.

- Cruickshank, Dan (1996). Fletcher, Banister; Saint, Andrew; Frampton, Kenneth; Jones, Peter Blundell (eds.). ISBN 0-7506-2267-9.

- Kay, N. W., ed. (1955). The Modern Building Encyclopaedia: An Authoritative Reference to All Aspects of the Building and Allied Trades. New York, NY: Philosophical Library. )

- Lagassé, Paul, ed. (2000). "abacus". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. LCCN 00-027927.

External links

- Abacus, Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities