Action of 18 November 1809

| Action of 18 November 1809 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mauritius campaign of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

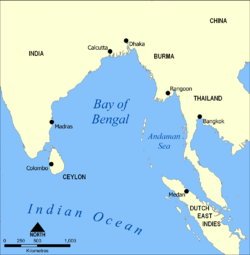

Location of the action of 18 November 1809 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Jacques Hamelin |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Two frigates One brig[contradictory] |

Three East Indiamen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

4 killed 2 wounded Three East Indiamen captured (one subsequently recovered) | ||||||

The action of 18 November 1809 was the major engagement of a six-month cruise by a French

The largest British merchant ship, Windham commanded by John Stewart, took advantage of a disrupted French formation to attack the frigate Manche. The two ships fought for an hour before Manche disengaged and Windham fled. The other two Indiamen declined to join the action and offered only token resistance to the more powerful French warships before surrendering. Windham evaded the French pursuit for five days before also being captured by the French flagship, Vénus.

Hamelin's force began transporting their captured

The action was one of three losses of East Indiamen convoys during 1809, which prompted the British to substantially increase their naval presence in the Indian Ocean during 1810.

Background

Following the decisive

In late 1808, the

After arriving in the Indian Ocean, Hamelin dispersed his frigates in the

Hamelin's cruise and Stewart's convoy

In July 1809, Hamelin departed Île de France in the frigate

Hamelin led his small squadron towards the Bay of Bengal. On the way there, Vénus captured the EIC armed ship Orient on 26 July. Hamelin then turned east in search of more British shipping to attack, capturing several small merchant vessels off the Nicobar Islands.[5] He then turned south, towards the small trading port of Tappanooly (modern Sibolga) on Sumatra. On 10 October, the squadron raided Tappanooly, capturing its small British population and razing the town.[1] Hamelin then turned north, back towards the Bay of Bengal.[citation needed]

Months earlier, a convoy of three East Indiamen –

Stewart's three vessels had cargo capacities of approximately 800

Engagement

At 06:00 on 18 November 1809, with the sailing season almost at an end, Hamelin sighted Stewart's convoy[where?] travelling northwards and gave chase. Ship for ship, the East Indiamen were outclassed by the French frigates, which were faster, stronger, more powerful, better armed and better trained for military action. In convoy, however, the British were still a tough target which could damage the French ships, which were thousands of miles from any friendly port. Four years earlier, at the Battle of Pulo Aura, a convoy of 29 East Indiamen had driven off a powerful French squadron by pretending to be ships of the line. However that ruse had been widely reported on both sides, so was unlikely to work again.[9]

The French squadron became disorganised in its initial pursuit of the British, with Manche falling substantially to

By 08:00, it was clear that Stewart's plan was going to fail: Charlton and United Kingdom had not joined his attack, falling far behind Windham as their captains deliberately checked the advance towards the French.[10] Although Stewart now faced a superior foe alone, he had no option but to continue the attack: his ship was now too close to attempt to flee from the French frigate.[6] Manche's commander, Captain Dornal de Guy, opened fire at 09:30, repeatedly hitting Windham as she approached. Stewart, aware of his gunners' poor accuracy, held fire until his ship was as close as he could get to the more nimble French ship. When Windham finally opened fire the results were disappointing: the entire broadside fell far short of the French ship.[10] The more manoeuvrable Manche now approached Windham at close range, with the two ships firing at one another for over an hour. The other two East Indiamen did not move to support Windham, instead firing occasional shots at extreme range, to no effect.[6]

Hamelin ordered Manche to leave the battered Windham and rejoin the rest of the French squadron. Dornal de Guy pulled his ship away at 12:00; Stewart used the break in the action to effect rudimentary repairs. Hamelin sent Manche and Créole after the slow Charlton and United Kingdom, while his own ship Vénus closed with Windham. Stewart now decided that the battle was hopeless; with the agreement of his officers, he determined to abandon the other ships and attempt to escape alone.[11] Manche and Créole rapidly overhauled and captured Charlton and United Kingdom, whose captains made no attempt to escape and surrendered after only a token resistance. However, Vénus struggled to catch Windham, as Stewart threw all non-essential stores overboard in an effort to make his ship lighter and faster. The two ships became separated from the other vessels and continued the chase for five days. At 10:30 on 22 November Hamelin finally caught the British ship, which surrendered.[12]

Return to Île de France

Bellone, under Captain

On 19 December, the first winter storm struck the French squadron. In the heavy waves and high winds, first Windham and then Vénus were separated from the convoy, Manche marshalling the remaining ships and continuing the southwards journey. Windham's French prize crew were able to regain control of their ship and continued on to Île de France alone, but Vénus was struck by an even larger hurricane on 27 December and lost all three topmasts in the gale.[12] The French crew panicked as the storm began, and refused to attend to the sails or even close the hatches: as a result the vessel almost foundered as huge amounts of water poured into the ship. In desperation, Hamelin called Captain Stewart to his cabin and requested that his men save the ship but demanded that Stewart give his word that his men would not attempt to escape or seize the frigate.[14] Stewart refused to give any such guarantee but agreed to help repair the damage and bring the ship to safety. After securing the weapons lockers aboard, Hamelin agreed and Stewart and his men cut away the wrecked masts and pumped the water out of the hold, repairing the ship so that she was able to continue her journey without fear of foundering.[12]

On 31 December, the battered Vénus docked in

Aftermath

Casualties in the battle were minimal, the British losing four killed and two wounded while the French recorded no casualties at all.[6] The significance of the action lies in the ease with which French frigates operating from Île de France were able to attack and capture vital trade convoys without facing serious opposition. The action of 18 November was the second occasion in 1809 in which a British East India convoy was destroyed and another would be lost in the action of 3 July 1810 the following year. These losses were exceptionally heavy, especially when combined with the 12 East Indiamen wrecked during 1809, and would eventually provoke a massive buildup of British forces in late 1810.[16] Despite the French success Vénus was never again able to operate independently in this manner. Hamelin was needed during 1810 to operate against the strong British frigate squadrons that returned in the spring to harass his cruisers and prepare for the planned invasions of Île Bonaparte and Île de France using the soldiers stationed on Rodrigues. The French commodore was ultimately unable to prevent these operations and was eventually captured in the action of 18 September 1810, a personal engagement with Rowley on HMS Boadicea.[17]

Notes

- ^ a b c d Gardiner, p. 93

- ^ a b Gardiner, p. 92

- ^ a b Woodman, p. 283

- ^ James, p. 262

- ^ James, p. 200

- ^ a b c d e f James, p. 201

- ^ Brenton, p. 398

- ^ Taylor, p. 251

- ^ Adkins, p. 185

- ^ a b Taylor, p. 252

- ^ Taylor, p. 253

- ^ a b c James, p. 202

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, P. K. Crimmin, (subscription required), Retrieved 30 October 2008

- ^ Taylor, p. 254

- ^ a b Woodman, p. 284

- ^ Taylor, p. 267

- ^ Gardiner, p. 96

References

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11916-3.

- Brenton, Edward Pelham (1825). The Naval History of Great Britain, Vol. IV. C. Rice.

- Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Taylor, Stephen (2008). Storm & Conquest: The Battle for the Indian Ocean, 1809. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22467-8.

- ISBN 1-84119-183-3.