Bethlehem Down

| Bethlehem Down | |

|---|---|

| Key | D minor |

| Period | Early 20th century |

| Genre | Christmas carol |

| Form | SATB choir |

| Occasion | The Daily Telegraph Christmas carol competition |

| Text | Bruce Blunt |

| Melody | Peter Warlock |

| Composed | 1927 |

| Published | 24 December 1927 in The Daily Telegraph |

| Publisher | The Daily Telegraph (1927), Winthrop Rogers (1928) |

"Bethlehem Down" is a

In 1930, Warlock composed an arrangement of "Bethlehem Down" for solo voice and keyboard accompaniment. It was the last piece of music that Warlock wrote, less than three weeks before he died. The solo arrangement uses the soprano line from the SATB version as its melody. It features more complex harmony than the choral arrangement, highlighting the text in a more sombre manner.

Context

Composition

Peter Warlock was a prolific composer of songs, with over 119 to his name. His choral music is less well-known, but within that genre, "Bethlehem Down" is one of Warlock's most famous carols.[2][3] The poet and journalist Bruce Blunt told the story behind the creation of "Bethlehem Down" in a letter to Gerald Cockshott, dated 1943.[4] He said that he and Peter Warlock were short on money in the run up to Christmas in 1927, so they had the idea to write a Christmas carol together in the hopes it would be published and earn them enough money for alcohol (or as Blunt called it, an "immortal carouse").[2][5] Whilst on a night-time walk between two pubs—The Plough in Bishops Sutton and The Anchor in Ropley[6]—Blunt thought up the words to "Bethlehem Down". He sent the text to Warlock who set it to music within a few days. The completed carol was entered into The Daily Telegraph's Christmas carol competition and won.[7] It was published in the paper on 24 December 1927.[5][b] The carol would be published again the following year by Winthrop Rogers (now Boosey & Hawkes).[9] Warlock and Blunt worked on other carols together, including The Frostbound Wood,[6] which was published in the Radio Times on 20 December 1929.[10]

Solo arrangement

In 1930, Warlock arranged a solo version of "Bethlehem Down".[11] It was written especially for Arnold Dowbiggin to perform as part of a Christmas recital in Lancaster Priory Church.[12] The musicologist Barry Smith writes that in this late period of Warlock's life, he was feeling increasingly depressed.[13] Dowbiggin himself wrote that the solo arrangement of "Bethlehem Down" is "a source for sorrow".[14] The solo arrangement of "Bethlehem Down" was the last piece of music Warlock wrote,[13] less than three weeks before his death.[15] Dowbiggin said that he received the manuscript on the day that Warlock died.[14]

Composition

Choral arrangement

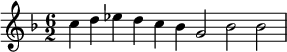

The choral arrangement of "Bethlehem Down", written and published in 1927, is written for unaccompanied

Each verse ends with a phrase which Smith describes as "haunting".[3]

Solo arrangement

In the solo arrangement of "Bethlehem Down", the solo part uses the same melody as the SATB soprano line. The solo is accompanied by a new keyboard part[12] which can be performed by either piano or organ.[15] Trevor Hold describes the keyboard accompaniment as more "intricate" than the SATB arrangement.[15] It features more complex harmony than the SATB version with additional counterpoint, differences in texture, and a passage linking penultimate and final verses—reminiscent of Warlock's other carol, Corpus Christi.[20] The solo arrangement accompaniment features what Copley calls the "gloom motif"—a motif used in other Warlock pieces consisting of a chromatic sequence played over a pedal. Copley describes the motif as "desolate",[19] and Smith writes that the accompaniment as a whole "highlights the inherent sadness of Blunt's poem".[13]

Text

Smith writes that, although Warlock was not religious and was anti-Christian, he liked the story of Christmas.[21] Hold writes that Blunt's text takes an "oblique" approach to carol text, contrasting the Christmas story ("Myrrh for its sweetness, and gold for a crown") with the later life of Jesus ("Myrrh for embalming, and wood for a crown").[15]

When He is King we will give him the King's gifts,

Myrrh for its sweetness, and gold for a crown,

"Beautiful robes", said the young girl to Joseph

Fair with her first-born on Bethlehem Down.

Bethlehem Down is full of the starlight

Winds for the spices, and stars for the gold,

Mary for sleep, and for lullaby music

Songs of a shepherd by Bethlehem fold.

When He is King they will clothe Him in grave-sheets,

Myrrh for embalming, and wood for a crown,

He that lies now in the white arms of Mary

Sleeping so lightly on Bethlehem Down.

Here He has peace and a short while for dreaming,

Close-huddled oxen to keep Him from cold,

Mary for love, and for lullaby music

Songs of a shepherd by Bethlehem fold.

Reception

Smith writes that "Bethlehem Down" is "surely the finest of all [Warlock's] choral works"[3] and a rare example of a modern carol which captures the essence of the genre.[18] The music critic Wilfrid Mellers described it as a small miracle.[21] Music journalist Alexandra Coghlan writes that the piece is Warlock's "unquestioned carol masterpiece",[22] and is particularly impressive given the fact its creation arose from the simple need for money and alcohol.[23] BBC Music Magazine writes that the carol has a beautiful and sombre tone[24] which can act as a change in pace in carol services.[25]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Warlock first used this pseudonym in 1916 when publishing an article in The Music Student journal.[1]

- ^ The Telegraph published Warlock's handwritten manuscript, featuring what The New Oxford Book of Carols describes as "archaic diamond-headed notes."[8]

Citations

- ^ Smith 1994a, p. 103.

- ^ a b Smith 1994a, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b c d Smith 1994b.

- ^ Foreman 1987, p. 257.

- ^ a b Copley 1979, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b Bradley 1999, p. 393.

- ^ Hewett, Ivan (15 December 2019). "British Composers Have Started a New Craze for Christmas carols". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Keyte & Parrott 1998, p. 112.

- ^ Copley 1979, p. 308.

- ^ Copley 1979, p. 141.

- ^ Copley 1979, p. 142.

- ^ a b Copley 1979, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Smith 1994a, p. 279.

- ^ a b Dowbiggin 1994, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e Hold 2005, p. 369.

- ^ Coghlan 2016, p. 156.

- ^ a b Hold 2005, p. 315.

- ^ a b Smith 1994a, p. 249.

- ^ a b Copley 1979, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Copley 1979, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Mellers 1997, p. 97.

- ^ Coghlan 2016, p. 155.

- ^ Coghlan, Alexandra (21 December 2020). "Hark! The Secret Messages From the 10 Nation's Favourite Christmas Carols". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Bethlehem Down". BBC Music Magazine. 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Parr, Freya (5 November 2021). "Six of the Best Pieces of Christmas Choral Music". BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

Works cited

- ISBN 0-14-02-7526-6.

- Coghlan, Alexandra (2016). Carols From King's : The Stories Of Our Favourite Carols From King's College. London: ISBN 9781785940941.

- Copley, I. A. (1979). The Music of Peter Warlock: A Critical Survey. London: ISBN 0-234-77249-2.

- Dowbiggin, Arnold (1994). "Peter Warlock Remembered". In ISBN 0-905210-76-X.

- Foreman, Lewis (1987). From Parry to Britten : British Music in Letter 1900-1945. United States: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-03-9.

- ISBN 1-84383-174-0.

- Keyte, Hugh; ISBN 0-19-353322-7.

- ISBN 1-900541-45-9.

- ISBN 0-19-816310-X.

- Smith, Barry (June 1994b). "A Supreme Carollist". Choir & Organ. Vol. 2, no. 3.

External links

- First publication of "Bethlehem Down" in The Daily Telegraph, 24 December 1929

- Manuscript for solo arrangement of "Bethlehem Down"

- Bethlehem Down: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project