Black Terror (ship)

Black Terror was a fake warship used in the

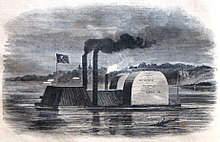

Not wanting Indianola to be repaired and enter Confederate service like Queen of the West, Union Navy officer David Dixon Porter had a fake ironclad constructed to bluff Confederate salvage workers into destroying the wreck of Indianola. A flatboat or barge was expanded with logs, and outfitted with fake cannons, lifeboats, and smokestacks. The fake vessel cost less than $9 (equivalent to $189 in 2020) and was named Black Terror. At 23:00 on February 25, the fake ship was released downstream, and successfully convinced the Confederates that it represented a real threat. Believing they faced an actual warship, the Confederate salvage crew of Indianola blew up the ship's remains, although some cannons were later recovered. The naval historian Myron J. Smith has since suggested that Black Terror was actually a later fake designed to reveal the location of Confederate artillery batteries, and that the story has been conflated with a possible earlier ruse aimed at forcing the destruction of Indianola.

Background

In 1861, during the opening stages of the

Farragut made another attempt in June, this time accompanied by an infantry force led by

Operations on the Red

Led by

Cruise of Black Terror

With the remains of Indianola in Confederate possession, salvage crews and impressed plantation slaves began working on the ship to get it repaired and refloated. United States Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles believed that Indianola represented a significant threat in potential Confederate hands and ordered that a squadron of ships be sent to take the wreck back. Having recently lost two other rams to Confederate fire, Porter did not believe he had a sufficient number of ships for Welles's proposed squadron,[17] and the ships he did have would have been at risk of being outmaneuvered by the faster William H. Webb and Queen of the West. Instead, Porter decided to create a fake ironclad to bluff the Confederates into abandoning the salvage of Indianola.[17][18]

Porter, who described the loss of Indianola as "the most humiliating affair that has occurred during this rebellion",

Black Terror was set free into the Mississippi at 23:00 on February 25,

The Richmond Examiner, a Confederate newspaper, lambasted the destruction of Indianola, stating "laugh and hold your sides lest you die of a surfeit of derision".[17] The Vicksburg Whig also added criticism.[30] Another Confederate attempt to raise the remains of Indianola took place in early March, but was unsuccessful except for the recovery of three cannons.[30][31] Queen of the West and William H. Webb, which were still damaged from their fight with Indianola, withdrew up the Red[26] and were no longer threats to the Union on the Mississippi.[17] Later that year, both Vicksburg and Port Hudson were taken by Union forces.[17] Vicksburg fell on July 4 after joint army-navy operations and the lengthy Siege of Vicksburg[32] and Port Hudson surrendered on July 9, after hearing of the fall of Vicksburg.[33] The Mississippi River was now under Union control.[34]

Two ships hypothesis

Myron J. Smith wrote in his work Joseph Brown and his Civil War Ironclads that Porter had sent an earlier, less elaborate fake ironclad downriver towards the site of Indianola, which was the one that convinced the Confederates to destroy Indianola. Smith also refers to a letter from Porter which was published on March 25 that stated that he had not known for certain that Indianola was in Confederate hands when he sent the fake ironclad. As the second fake vessel, Black Terror would have been sent downriver in early March in order to provide evidence on where the Confederate batteries were located.[35]

Notes

References

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 118.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 128–133.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 135–137.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 148, 151, 153.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 153.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 22, 27.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 154–156.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 60.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 214.

- ^ a b "Indianola". Naval History and Heritage Command. July 21, 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Miller 2019, p. 304.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Barnhart 2003.

- ^ Hearn 2000, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 68.

- ^ a b Smith 2017, p. 211.

- ^ Legan 2000, p. 294.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 304–305.

- ^ a b c Miller 2019, p. 305.

- ^ Groom 2010, p. 250.

- ^ Legan 2000, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 67.

- ^ Chatelain 2020, p. 219.

- ^ a b Legan 2000, p. 296.

- ^ Smith 2017, p. 212.

- ^ a b Hearn 2000, p. 118.

- ^ Smith 2017, p. 214.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 157–173.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Smith 2017, pp. 209–210.

Sources

- Barnhart, Donald L. (September 2003). "Admiral Porter's Ironclad Hoax". ISSN 1046-2899.

- Chatelain, Neil P. (2020). Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861–1865. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-510-6.

- ISBN 978-0-307-27677-3.

- Hearn, Chester G. (2000). Ellet's Brigade: The Strangest Outfit of All. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2559-8.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Legan, Marshall Scott (Summer 2000). "The Confederate Career of a Union Ram". The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Society. 41 (3): 277–300. JSTOR 4233674.

- ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Smith, Myron J. (2017). Joseph Brown and His Civil War Ironclads: The USS Chillicothe, Indianola, and Tuscumbia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-9576-4.