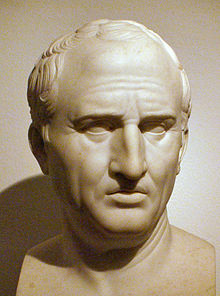

De Divinatione

De Divinatione (Latin, "Concerning

Contents

De Divinatione is set in two books, taking the form of a

).De Divinatione may be considered as a supplement to Cicero's De Natura Deorum.[1] In De Divinatione, Cicero professes to relate the substance of a conversation held at Tusculum with his brother, in which Quintus, following the principles of the Stoics, supported the credibility of divination, while Cicero himself controverted it.[1] The dialogue consists of two books, in the first Quintus enumerates the different kinds or classes of divination, with reasons in their favour.[1] The second book contains a refutation by Cicero of his brother's arguments.[1]

In the first book Quintus, after observing that divinations of various kinds have been common among all people, remarks that it is no argument against different forms of divination that we cannot explain how or why certain things happen.[2] It is sufficient, that we know from experience and history that they do happen.[2] He argues that although events may not always succeed as predicted, it does not follow that divination is not an art, any more than that medicine is not an art, because it does not always cure.[2] Quintus offers various accounts of the different kinds of omens, dreams, portents, and divinations.[2] He includes two remarkable dreams, one of which had occurred to Cicero and one to himself.[2] He also asks if Greek history with its various accounts of omens should be also considered a fable.[2]

In the second book Cicero provides arguments against auguries, auspices, astrology, lots, dreams, and every species of omens and prodigies.[3] For example, he argues that he dreamt of Marius during his banishment because he often thought about him, not because it was some sort of omen. He states that during one's sleep, the soul is in a relaxed state and remnants of one's waking thoughts move freely within the soul.[4] It concludes with a chapter on the evils of superstition, and Cicero's efforts to extirpate it.[3] The whole thread is interwoven by curious and interesting stories.[3]

De Divinatione is notable as one of posterity's primary sources on the workings of Roman religion, and as a source for the conception of scientificity in Roman classical antiquity.[5]

Quotes

- Nothing so absurd can be said that some philosopher had not said it. (Latin: Sed nescio quo modo nihil tam absurde dici potest quod non dicatur ab aliquo philosophorum) (II, 119)

- That old saying by Latin: Vetus autem illud Catonis admodum scitum est, qui mirari se aiebat quod non rideret haruspex haruspicem cum vidisset) (II, 24, 51)

Citations

References

- Dunlop, John (1827), History of Roman literature from its earliest period to the Augustan age, vol. 1, E. Littell

Further reading

- Engels, David, Das römische Vorzeichenwesen (753–27 v.Chr.). Quellen, Terminologie, Kommentar, historische Entwicklung, Stuttgart 2007, pp. 129–164.

- Hahmann, Andree (2019). "Cicero Defining the Stoic Science of Divination". Apeiron. 52 (3): 317–337. .

- Pease, Arthur Stanley, M. Tulli Ciceronis de Divinatione, 2 vol., Urbana 1920–1923 (reprint Darmstadt 1963).

- JSTOR 300365.

- Schultz, Clelia E. (2014). Commentary on Cicero, De Divinatione I. Michigan Classical Commentaries. Ann Arbor.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dyck, Andrew R. (2020). Commentary on Cicero, De Divinatione II. Michigan Classical Commentaries. Ann Arbor.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wardle, David, Cicero on divination : De divinatione, book 1. Transl., with introd. and historical commentary by David Wardle, Oxford 2006.

- Wynne, J. P. F. (2019). Cicero on the Philosophy of Religion: On the Nature of the Gods and On Divination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107707429.