Dijing Jingwulue

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Dijing Jingwulue | |

|---|---|

Hanyu Pinyin | dìjīng jǐngwù lüè |

| Wade–Giles | ti-ching ching-wu lüeh |

| IPA | [tî.tɕíŋ tɕìŋ.û lɥê] |

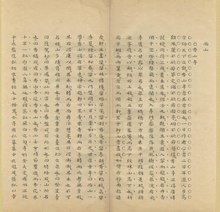

The Dijing Jingwulue (

Yu Yizheng (于奕正) and Zhou Sun (周损), two scholars outside of official circles were Liu's assistants who helped in compiling the book.

The preface reveals Liu as the actual author, while Yu was a compiler with Zhou acting as something of an assistant to the other two. However, Yu was a native of Beijing, capital of Ming dynasty China, and a scholar of local traditions. Liu may have just polished the prose, but gained most of the prestige. Liu dates the preface as 1635, the same year Yu died in Nanjing, three years before troops of the new dynasty attacked Beijing.

A celebration of a city's ambiance that would disappear behind the secluded walls of a conquered city, the work features descriptions of multiple gardens and estates that would soon vanish forever. Ming dynasty Beijing, in contrast with the later conservative

The Dijing Jingwulue is also notable for being the first text to mention that

References

- Carpenter, Bruce E., "Survey of Scenery and Monuments in the Imperial Capital, A Seventeenth Century Chinese Classic", Tezukayama University Review (Tezukayama daigaku ronshū), Nara, Japan, no. 61, 1988, pp. 62–71. ISSN 0385-7743

- Ledderose, Lothar (2004). 'Changing the Audience' in Religion and Chinese Society (Vol. 1). A Centennial Conference of the École franşaise d'Extrême-Orient. John Lagerwey Ed., p385-409

Notes

- ^ Ledderose 2004: 393