Field holler

The field holler or field call is mostly a historical type of

There had also been some instances where some white oat farmers in close proximity to black people in the southern United States adopted and employed the field holler.[3]

Description

It was described by

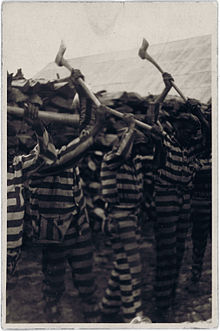

Verbal, improvised lines were used as cries for water and food and cries about what was happening in their daily lives, as expressions of religious devotion, a source of motivation in repetitive work, and a way of presenting oneself over across the fields. They described the labor being done (e.g., corn shucking songs, mule-skinning songs) recounted personal experiences or the singer's thoughts, subtly insulted white work attendants, or used folk themes. An unidentified singer of a Camp Holler was urged on with shouts and comments by his friends, suggesting that the holler could also have a social role.[6] Call and response arose as sometimes a lone caller would be heard and answered with another laborer's holler from a distant field. Some street cries might be considered an urban form of holler, though they serve a different function (like advertising a seller's product); an example is the call of ‘The Blackberry Woman’, Dora Bliggen, in New Orleans.[7]

Origins

The field holler has origins in the

Influence

Field hollers, cries and hollers of the

The field holler may in turn have been influenced by blues recordings. No recorded examples of hollers exist from before the mid-1930s, but some blues recordings, such as Mistreatin' Mama (1927, Negro Patti) by the harmonica player Jaybird Coleman, show strong links with the field holler tradition.[9][10]

A white tradition of "hollerin'" may be of similar age, but has not been adequately researched. Since 1969 an annual

See also

- An African Song or Chant from Barbados

- Blue note

- Twelve-bar blues

- Blues ballad

- Holler Blues

- Kulning

- Afro-American Work Songs in a Texas Prison, a 1966 documentary film

References

- ^ Maultsby, Portia. "A History of African American Music". Carnegie Hall. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ^ ISBN 0-02-061740-2.

- from the original on 2020-10-02. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ^ 1950, Negro Folk Music of Alabama, Folkways

- ^ 1947, Negro Prison Songs, Tradition

- ^ 1941, Negro Blues and Hollers, Library of Congress

- ^ 1954, Been Here and Gone, Folkways

- ^ a b Curiel, Jonathan (August 15, 2004). "Muslim Roots of the Blues". SFGate. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 5, 2005. Retrieved August 24, 2005.

- ISBN 0-306-80155-8.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Jaybird Coleman:Biography". allmusic.com. Archived from the original on 2024-04-06. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

Sources

- Charlton, Katherine (2003). Rock Music Styles - a history. Mc Graw-Hill, 4th ed., pp. 3. ISBN 0-07-249555-3.

- Oxford Music Online: Grove Music

- Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans. 3rd. New York London: Norton, 1997. Print.

External links

- Recordings from The John and Ruby Lomax 1939 Southern States Recording Trip -> Hollers

- Recordings of hollers, done by Alan Lomax, 1947-1959 (Association for Cultural Equity)