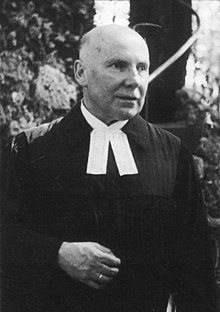

Friedrich von Bodelschwingh

Friedrich "Fritz" von Bodelschwingh (German:

Public health activities

Friedrich was the son of Reverend

Both Bodelschwinghs were concerned with inherited defects, and expressed distress at the increasing number of handicapped persons in Germany. In a speech on 29 January 1929 he referred to the "catastrophic development" of "the increasing number of weak ones in body and spirit."

Reich bishop in the commencing Struggle of the Churches

After its takeover of power the Nazi Reich's government aimed at streamlining the

In a mood of an emergency through an impending Nazi takeover functionaries of the then officiating executive bodies of the 28 Protestant regional church bodies stole a march on the German Christians. Functionaries and activists worked hastily on negotiating between the 28 Protestant regional church bodies a legally indoubtable unification. On 25 April 1933 three men convened, Hermann Kapler, president of the old-Prussian Evangelical Supreme Church Council – representing

On 27 May 1933 representatives of the 28 church bodies gathered in Berlin and against a minority, voting for Ludwig Müller, Friedrich von Bodelschwingh, Jr., a member of the

Once the Nazi government had figured out that the Protestant church bodies would not be streamlined from within using the German Christians, they abolished the constitutional

This act clearly violated the status of the Protestant regional churches as statutory bodies (German: Körperschaften des öffentlichen Rechts), subjecting them to Jäger's orders.[4] Bodelschwingh resigned as Reich's Bishop the same day. On 28 June Jäger appointed Müller as new Reich's Bishop and on 6 July as leader of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union.

Opposition to other Nazi policies

Bodelschwingh discussed both

In May 1940 Pastor Paul Braune, Vice President of the Central Board for Inner Missions of the German Protestant churches and head of the Hoffnungstal Institutions, met with Bodelschwingh at Bethel to discuss the Nazi "green forms" which he had been instructed to fill out, authorising the transfer of "feebleminded" girls from the Hoffnungstal Institutions. The two men were deeply alarmed over disturbing reports of deaths of former patients who were shipped off and strange obituaries which had appeared. In February 1941 when a physician's commission arrived at Bethel to force Bodelschwingh to fill out the green forms, he refused. Staff members expressed their willingness to forcibly resist any attempted transportation of sick persons by force and the commission eventually departed. A month later the Nazi regime banned the institute press.

On 21 September 1940, war correspondent

According to the noted psychiatrist Karl Stern's memoir, The Pillar of Fire (p. 119), "There was a famous Lutheran pastor, Bodelschwingh, who built up a huge colony of feeble-minded, idiots and epileptics in Bethel in Western Germany. During the war, when the Nazis carried out the slaughter of all mental patients, Pastor Bodelschwingh insisted that he would be killed together with his inmates. It was only on the basis of his international fame that the politicians let him get away with it, and let him and the inmates of his colony live. This was a kind of last-ditch stand of Christianity."

Death and posthumous recognitions

After the war, Bodelschwingh and the Bethel Institute set up the Bethel Search Service to help locate missing family members. Bodelschwingh died in January 1946 and was buried in the Zions Church in Bethel.

Friedrich von Bodelschwingh appeared three times on German postage stamps: in 1967 when the German Federal post office commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Bethel hospitals, in 1977 to commemorate Bodelschwingh's 100th birthday, and in 1996 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death.

Von Bodelschwingh Foundations today

The von Bodelschwingh Foundations of Bethel are still in operation, helping more than 14,000 persons in clinics, homes, schools,

Literature

- Alfred Adam (1955), "Bodelschwingh, Friedrich", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 2, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 351–352; (full text online)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz (1975). "Bodelschwingh, Friedrich von". In Bautz, Friedrich Wilhelm (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 1. Hamm: Bautz. col. 649–651. ISBN 3-88309-013-1.

- Benad, Matthias: "Bethels Verhältnis zum Nationalsozialismus", in: ders./ Regina Mentner (Hg.), Zwangsverpflichtet. Kriegsgefangene und zivile Zwangsarbeiter in Bethel und Lobetal 1939–1945, Bielefeld 2002, S. 27-66.

- Hochmuth, Anneliese: Spurensuche. Eugenik, Sterilisation, Patientenmorde und die v. Bodelschwinghschen Anstalten Bethel 1929–1945, Bielefeld 1997.

- ISBN 3-10-039303-1.

References

- ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ^ With about 18 million parishioners the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union was by far the biggest Protestant regional church body within Germany. According to the census in 1933 there were in Germany, with an overall population of 62 million, 41 million parishioners enlisted with one of the 28 different Lutheran, Reformed and United Protestant church bodies, making up 62.7% as against 21.1 million Catholics (32.5%).

- ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ISBN 3-923095-61-9.