Letters of a Javanese Princess

Bagindo Dahlan Abdullah, Zainudin Rasad, Sutan Muhammad Zain, and Djamaloedin Rasad (Malay, 1922); Armijn Pane (Malay, 1938); Louis Charles Damais (French, 1960) | |

| Country | Dutch East Indies |

|---|---|

| Language | Dutch language |

| Publisher | G. C. T. van Dorp |

Publication date | 1911 (first edition) |

Published in English | 1920 |

Letters of a Javanese Princess (

History

Kartini (1879–1904) was the daughter of an aristocratic Javanese family from Jepara.[1] Unusually for the time, she was schooled in the Dutch language and read, wrote and corresponded extensively as a youth living in aristocratic seclusion.[2][3] She had hoped to leave home to obtain further education, but was denied by her family, since it was unheard of at that time.[3] Therefore she was mostly self-educated, and soon became very well-informed on colonial politics, modern issues, and was an admirer of Abdoel Rivai.[1] The letters she wrote, which were written between 1899 and 1904, were addressed to around ten Europeans whom she mostly met in Java, including the Indies Minister of Education Jacques Henrij Abendanon and his wife Rosa Abendanon, Nellie van Kol (wife of the politician Henri van Kol), Marie Ovink-Soer (wife of the Resident of Jepara) and so on.[4][3] In the letters she discusses her views on politics and culture, her family life, and her relationships.

After her untimely death in 1904 at the age of 25, J. H. Abendanon began to collect letters Kartini had written to him and other Europeans.[5] Selected letters were edited by Abendanon and published by G. C. T. van Dorp in 1911, both in Java and in The Hague, under Abendanon's evocative title Through darkness to light.[6] The book sold very well and several more printings were issued in the 1910s; Abendanon used some of the proceeds to found girls' schools in the Indies.[7][5]

Because of its popularity, the book was eventually translated and published in other languages. Starting in late 1919 some letters were translated into English and serialized in

Significance and legacy

The publication of the book, and its subsequent commercial success, turned Kartini into a household name in the Indies and in the Netherlands. She became a symbol of the Dutch Ethical Policy to liberal Europeans and of the Indonesian National Awakening to Indonesian nationalists. The tension between these two uses of her ideas can be seen in Abendanon's foreward to the first edition, in which he praised Kartini's progressive ideals but also warned that lofty ideals can be dangerous.[2] Abendanon heavily edited Kartini's letters, for example to remove references to polygamy from her family life.[2][3] The English editions also excluded some of the letters from the 1911 book, downplaying her criticism of European colonialism and paternalism.[8] Meanwhile the 1922 Malay edition, promoted heavily by the colonial education system, popularized Kartini and her ideas among Indonesians.[11]

For the next several decades, Kartini and this book became almost unknown outside the Indies/Indonesia and the Netherlands. There were nonetheless many new translations in other languages, including an

Selected editions and translations

- Door duisternis tot licht: gedachten over en voor het Javaansche volk / van wijlen Raden Adjeng Kartini; [verz. en ingel. door J.H. Abendanon]. (first Dutch edition, G. C. T. van Dorp, 1911)[13]

- Letters of a Javanese princess / by Raden Adjeng Kartini ; transl. from the Dutch by Agnes Louise Symmers; with a forew. by Louis Couperus. (first English translation,

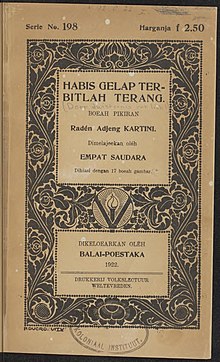

- Habis gelap terbitlah terang: boeah pikiran / Radén Adjeng Kartini ; dimelajoekan oléh empat saudara; dengan pendahoeloean daripada J.H. Abendanon (first Malay edition, Weltevreden (Batavia), 1922)[16]

- Lettres de Raden Adjeng Kartini: Java en 1900 / choisies et trad. par Louis Charles Damais; introd. et notes de Jeanne Cuisinier ; préf. de Louis Massignon (Mouton de Gruyter, Paris, 1960)[17]

- Raden Adjeng Kartini: letters of a Javanese princess / transl. from the Dutch by Agnes Louise Symmers; ed. and with an introd. by Hildred Geertz; pref. by Eleanor Roosevelt. (Norton, New York, 1964)[18]

- Letters of a Javanese princess (shortened English edition, Oxford University Press, 1976)[19]

- Door duisternis tot licht: gedachten over en voor het Javaanse volk (1976 reprint, Nabrink, Amsterdam)[20]

References

- ^ S2CID 253709174.

- ^ S2CID 148758565.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-4843-92-8.

- ^ Vierhout, M. (1944). Raden Adjeng Kartini 1879-1904 (in Dutch). Oceanus. p. 18.

- ^ a b Jedamski, Doris (22 June 2021). "Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879-1904). Pioneer for women's rights in the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia". Universiteit Leiden. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-5017-2060-4.

- ^ Vierhout, M. (1944). Raden Adjeng Kartini 1879-1904 (in Dutch). Oceanus. p. 6.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-4843-92-8.

- ISBN 978-979-18512-0-6.

- ^ Vierhout, M. (1944). Raden Adjeng Kartini 1879-1904 (in Dutch). Oceanus. p. 10.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-4843-92-8.

- S2CID 153805381.

- ^ "Door duisternis tot licht: gedachten over en voor het Javaansche volk". OCLC. 1911. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Letters of a Javanese princess". OCLC. 1920. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Letters of a Javanese princess". OCLC. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Habis gelap terbitlah terang: boeah pikiran". OCLC. 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Lettres de Raden Adjeng Kartini : Java en 1900". BNF (in French). Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Raden Adjeng Kartini: letters of a Javanese princess". OCLC. 1964. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Letters of a Javanese princess". OCLC. 1976. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Door duisternis tot licht: gedachten over en voor het Javaanse volk". OCLC. 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

External links

- 1922 Balai Pustaka translation of the book (in Malay/Indonesian) from the collection of Delpher

- 1911 first edition (in Dutch) from the collection of Delpher

- English translation of the book from Project Gutenberg

- Original Dutch text of the book from Project Gutenberg