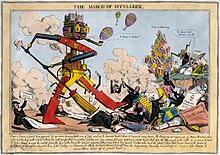

March of Intellect

The March of Intellect, or the 'March of mind', was the subject of heated debate in early nineteenth-century England, one side welcoming the progress of society towards greater, and more widespread, knowledge and understanding, the other deprecating the modern mania for progress and for new-fangled ideas.

The 'March' debate was seen by

Origins and context

The roots of the controversy over the March of intellect can be traced back to the spread of education to two new groups in England after 1800 – children and the working-class.[2] 1814 saw the first use of the term the 'march of Mind' as a poem written by Mary Russell Mitford for the Lancastrian Society,[3] and the latter's work in bringing education to children was soon rivalled by the efforts of the Established Church.[4]

The March of Intellect forms part of nineteenth-century debates over

meant something of a revolution in adult reading habits.The working classes had limited access to knowledge owing to poor literacy rates and the expensive cost of printed materials relative to wages. The Spa Fields Riots and Peterloo Massacre raised concerns about revolution and the violent unrest created resistance among the elite towards educating the lower classes.[9] Other conservative commentators supported educating the working class as a means of control. The Edinburgh Review commented in 1813 on the hopes of 'a universal system of education' that would 'encourage foresight and self-respect among the lower orders.' Through education, the working class would know their economic position in life and this would prevent further outbreaks of political unrest.[10] Liberal Whig supporters of educating the working classes, such as Henry Brougham, believed in 'the greatest happiness of the greatest number' outlined by Bentham's utilitarian philosophy.[11] The sciences were seen by these supporters as valuable knowledge for the working classes and debates on the best means of diffusing knowledge was debated.[12]

Peak

Interest in the so-called March of Intellect came to a peak in the 1820s. On the one hand, the

But the same phenomenon of the March of Intellect was equally hailed by conservatives as epitomising everything they rejected about the new age:

Victorian accommodation

The March of Mind was used by the Whigs as one argument for the

See also

- Condition of England

- Jacquerie

- Scottish Enlightenment

- Thomas Hood

- Whig theory of history

References

- ^ M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 177

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century (London 1922) pp. 163–5

- ^ M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 181n

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century (London 1922) pp. 163–4

- ^ Burns, James. "From 'Polite Learning' to 'Useful Knowledge' | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ "Science Publishing". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan, British History in the Nineteenth Century (London 1922) p. 164

- ^ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (Oxford 2008) pp. 171–2

- ISBN 0822383152.

- ^ "From 'Polite Learning' to 'Useful Knowledge' | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ "History, 1826: Unshackling education- UCL is established". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ "Science Publishing". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Quoted in M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 177

- ^ Alice Jenkins, Space and the March of Mind (2007) p. 16

- ^ M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank (London 1967) p. 177

- ^ "March of Intellect". The British Library. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ^ Schupbach, William (2011). "Flying postmen and magic glass". Wellcome Library. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ISBN 9780226902234.

- ^ Thomas Love Peacock, Nightmare Abbey and Crotchet Castle (London 1947) pp. 212–3, and pp. 105–6, p. 219

- ^ M. H Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp (Oxford 1953) p. 126

- ^ Quoted in Ben Wilson, Decency and Disorder (London 2007) p. 317

- ^ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (Oxford 2008) p. 611

- ^ E. Gargano, Reading Victorian Schoolrooms (2013) p. 140

- ^ J. Bristow, The Victorian Poet (2014) p. 8

See also Magee, D, 'Popular periodicals, common readers and the "grand march of intellect" in London, 1819-32' (DPhil, Oxon 2008).