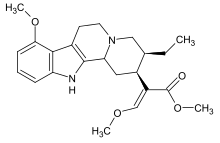

Mitragynine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Addiction liability | High[1] |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 102–106 °C[4] |

| |

| |

Mitragynine is an

Uses

Medical

As of April 2019[update], the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had stated that there were no approved clinical uses for kratom, and that there was no evidence that kratom was safe or effective for treating any condition.[9] This reiterated the conclusion of an earlier report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): As of 2023[update], kratom had not been approved for any medical use.[10][11] As of 2018[update], the FDA had noted, in particular, that there had been no clinical trials to study safety and efficacy of kratom in the treatment of opioid addiction.[12]

Ethnopharmacology

Analgesia

Mitragynine-containing kratom extracts, with their accompanying array of

Chronic pain

Kratom is commonly used in the United States as self-treatment for pain and opioid withdrawal.[16] A 2019 review of existing literature suggested the potential of kratom as substitution therapy for chronic pain.[17]

Opioid withdrawal

As early as the 19th century, kratom was in use for the treatment of

Recreational

Mitragynine and its metabolite

Dependence and withdrawal

Due at least in part to the activity on opioid receptors of mitragynine and its derivatives, kratom can result in dependence and lead to withdrawal symptoms when discontinued. Regular users report withdrawal symptoms comparable to that of other opioids following the discontinuation of kratom.[5][19] Addiction to kratom can lead to physical and psychiatric issues that can affect one's ability to work; there have also been reports of psychotic symptoms in those who are addicted.[5] A 2014 study which included 1118 male kratom users indicated that more than half of the regular users (67% of total subjects) experienced withdrawal when attempting to discontinue kratom with symptoms that included pain, muscle spasms, and insomnia.[13] In a study following 239 male kratom users in Malaysia consuming between 40 and 240 mg of mitragynine per day, 89% indicated a previous attempt of discontinuing kratom consumption which resulted in withdrawal symptoms ranging from mild (65% of subjects) to moderate/severe (35% of subjects).[20] In the same study, withdrawal symptoms ranged from physical symptoms such as nausea, diarrhea, and muscle spasms to psychological symptoms such as restlessness, anxiety, and anger but lasted less than 3 days for most subjects.[20] However, the results from this study may be obfuscated by the occasional addition of other substances in the kratom preparation such as dextromethorphan and benzodiazepines, which could contribute to the withdrawal symptoms.[20] In an animal study, mitragynine withdrawal symptoms were observed following 14 days of mitragynine i.p. injections in mice and included displays of anxiety, teeth chattering, and piloerection, all of which are characteristic signs of opioid withdrawal in mice and are comparable to morphine withdrawal symptoms.[20]

Solubility of mitragynine

The solubility of mitragynine from kratom in neutral-pH and alkaline water is very low (0.0187 mg/ml at pH 9).[21] The solubility of mitragynie in acidic water is higher (3.5 mg/ml at pH 4), however, this alkaloid can become unstable, so certain products, such as low-pH beverages, have a very short shelf life.[21] Many vendors offer concentrated kratom products with claims of improved mitragynine solubility, however, those products are often formulated with solvents such as propylene glycol, which can make products unpleasant.

Pharmacology

| Compound | Ki ) |

Ratio | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

MOR |

DOR |

KOR |

MOR:DOR:KOR | ||

| Mitragynine | 7.24 | 60.3 | 1,100 | 1:8:152 | [22] |

| 7-Hydroxymitragynine | 13.5 | 155 | 123 | 1:11:9 | [22] |

| Mitragynine pseudoindoxyl | 0.087 | 3.02 | 79.4 | 1:35:913 | [22] |

Pharmacodynamics

Mitragynine acts on a variety of receptors in the

Pharmacokinetics

| t1⁄2 (h) | 23.24 ± 16.07 |

|---|---|

| Vd (L/kg) | 38.04 ± 24.32 |

tmax (h)

|

0.83 ± 0.35 |

| CL (L/h) | 1.4 ± 0.73 |

Metabolism

| CYP | 1A2 | 3A4 | 2D6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μg/mL) | 39 (6) | 0.78 (6) | 3.6 (3), 0.636 (6) |

Mitragynine is primarily metabolized in the liver, producing many metabolites during both phase I and phase II.[7]

Phase I

During phase I metabolism, mitragynine undergoes

Phase II

During

Toxicology

Mitragynine toxicity in humans is largely unknown, as animal studies show significant species-specific differences in mitragynine tolerance.

Legality

In the United States, kratom and its active ingredients are not scheduled under

Research limitations

Inconsistencies in dosing, purity, and concomitant drug use makes evaluating the effects of mitragynine in humans difficult. Conversely, animal studies control for such variability but offer limited translatable information relevant to humans.[23] Experimental limitations aside, mitragynine has been found to interact with a variety of receptors, although the nature and extent of receptor interactions has yet to be fully characterized.[6] Additionally, the toxicity of mitragynine and associated kratom alkaloids have yet to be fully determined in humans, nor has the risk of overdose.[28] More studies are necessary to assess safety and potential therapeutic utility.[34]

References

- ^ {{Ventura, Frank BS1; John, Jaison S. MD1; Al-Saadi, Yamam I. MD1; Stevenson, Heather L. MD, PhD2; Khan, Kashif MD1. S2841 Autoimmune Hepatitis: Possible Relation to the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine?. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 116():p S1180, October 2021. | DOI: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000784896.23722.94}}

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ "指定薬物一覧" [List of designated drugs] (PDF). 障害福祉のお仕事の世界 (The world of disability welfare work) (in Japanese). Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Kratom profile (chemistry, effects, other names, origin, mode of use, other names, medical use, control status)". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA).

- ^ S2CID 8463133.

- ^ S2CID 2009878.

- ^ PMID 31308789.

- ^ PMID 23212430.

- ^ "FDA and kratom". US Food and Drug Administration. 3 April 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Kratom profile (chemistry, effects, other names, origin, mode of use, other names, medical use, control status)". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- clinical trialsin the United States, though it had been studied in cell culture and in animals. See Hassan et al. (2013), op. cit.

- ^ Gottlieb S (6 February 2018). "Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on the agency's scientific evidence on the presence of opioid compounds in kratom, underscoring its potential for abuse". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ PMID 29248691.

- ^ S2CID 3952200.

- ^ Kroll D. "Recreational Drug Kratom Hits the Same Brain Receptors as Strong Opioids". Chemical & Engineerin News. Retrieved 2020-05-15 – via Scientific American.

- PMID 27893147.

- S2CID 30013009.

- ^ An additional study included in the same review found that ~90% of 136 Malaysian kratom-users were substituting it for opioids, with ~84% reporting its effects helping with opioid withdrawal. See Swogger and Walsh (2018), op. cit.

- ISBN 9780890425541.

- ^ S2CID 207294013.

- ^ PMID 25793541.

- ^ PMID 11960505.

- ^ S2CID 157067698.

- S2CID 214771721.

- ^ "EMCDDA | Kratom profile (chemistry, effects, other names, origin, mode of use, other names, medical use, control status)". www.emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ S2CID 29310420.

- PMID 28484399.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 205537323.

- ^ Commons KM (2018-08-10). "Cracking Down on Kratom: FDA Investigation, Enforcement, Seizure, and Recall of Products Reported to Contain Kratom". Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI). Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ Gianutsos FG. "The DEA Changes Its Mind on Kratom". www.uspharmacist.com. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ "Kratom - an emerging drug of abuse". www.mangaloretoday.com. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner (2020-03-24). "FDA issues warnings to companies selling illegal, unapproved kratom drug products marketed for opioid cessation, pain treatment and other medical uses". FDA. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- PMID 31308789.