Monica Dickens

Monica Dickens | |

|---|---|

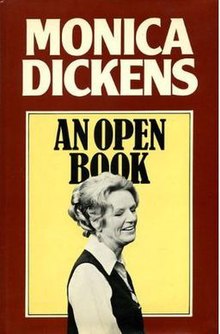

The cover of An Open Book, Dickens's 1978 autobiography | |

| Born | Monica Enid Dickens 10 May 1915 Paris, France |

| Died | 25 December 1992 (aged 77) Reading, Berkshire, England |

| Relatives | Charles Dickens (great-grandfather) Sir Henry Fielding Dickens (grandfather) |

Monica Enid Dickens, MBE (10 May 1915 – 25 December 1992) was an English writer, the great-granddaughter of Charles Dickens.[1]

Biography

Known as "Monty" to

One Pair of Feet (1942) recounted her work as a nurse, and subsequently she worked in an aircraft factory and on the Hertfordshire Express – a local newspaper in Hitchin; her experiences in the latter field of work inspired her 1951 book My Turn to Make the Tea.[2]

Soon after this, she moved from her home in Hinxworth in Hertfordshire to the United States after marrying a United States Navy officer, Roy O. Stratton, who died in 1985. They adopted two daughters, Pamela and Prudence. The family lived in Washington, D.C., and Falmouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, producing the 1972 book of the same name. She continued to write, most of her books being set in Britain. She was also a regular columnist for the British women's magazine Woman's Own for twenty years (without admitting to being an expatriate).

Dickens had strong humanitarian interests which were manifested in her work with the

In 1978, Monica Dickens published her

Adult books

- One Pair of Hands (Michael Joseph, 1939; re-published by Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, and Penguin Books Pty Ltd, Mitcham, 1961, book number 1535)

- Mariana (1940; re-published in 1999 by Persephone Books)

- One Pair of Feet (1942) (adapted for film as The Lamp Still Burns)

- Edward's Fancy (1943)

- Thursday Afternoons (1945)

- The Happy Prisoner (1946) (adapted as a BBC TV play in 1965)[6]

- Yours Sincerely (1947), in collaboration with Beverley Nichol

- Joy and Josephine (1948)

- Flowers on the Grass (1949)

- My Turn to Make the Tea (1951)

- No More Meadows (1953)

- The Winds of Heaven (1955; re-published in 2010 by Persephone Books)

- The Angel in the Corner (1956)

- Man Overboard (1958)

- The Heart of London (1961)

- Cobbler's Dream (1963; re-published in 1995 as New Arrival at Follyfoot)

- The Room Upstairs (1964)

- Kate and Emma (1965)

- The Landlord's Daughter (1968)

- The Listeners (1970)

- Cape Cod (1972) - Viking Press – non-fiction with William Berchen

- Talking of Horses (1973) – non-fiction

- Last Year When I Was Young (1974)

- An Open Book (William Heinemann Ltd, 1978; re-published by Penguin Books, 1980, ISBN 0-14-005197-X) – autobiography

- A Celebration (1984)

- A View From The Seesaw (1986, published by Dodd, Mead, ISBN 978-0-396-08526-3

- Dear Doctor Lily (1988)

- Enchantment (1989)

- Closed at Dusk (1990)

- Scarred (1991)

- One of the Family (1993)

Children's books

The World's End series:

- The House at World's End (1970)

- Summer at World's End (1971)

- World's End in Winter (1972)

- Spring Comes to World's End (1973)

The Follyfoot series:

- Follyfoot (1971)

- Dora at Follyfoot (1972)

- The Horses of Follyfoot (1975)

- Stranger at Follyfoot (1976)

The book Cobbler's Dream also contains the same characters as in the Follyfoot series.

The Messenger series:

- The Messenger (1985)

- Ballad of Favour (1985)

- Cry of a Seagull (1986)

- The Haunting of Bellamy 4 (1986)

Non-series:

- The Great Escape (1975)

Films

- The Lamp Still Burns (1943) (adapted from her 1942 novel One Pair of Feet)

- Love in Waiting (1948) (adapted from her original idea)

- Life in Her Hands (1951) (original screenplay with Anthony Steven)[7]

Strine

In late 1964 Dickens was visiting Australia to promote her works. It was reported in the

See also

References

- ^ Dickens Family Tree website

- ^ a b Charles Pick. "Obituary: Monica Dickens". The Independent, 31 December 1992.

- ^ "Monica Dickens, Prolific Author And Social Worker, Is Dead at 77 (Published 1992)". The New York Times. Associated Press. 27 December 1992.

- ^ "Nostalgic reunion for the stars of Follyfoot". yorkshirepost.co.uk.

- ^ "Kaleidoscope". 28 March 1947. p. 35 – via BBC Genome.

- ^ "The Happy Prisoner". 26 June 1955. p. 14 – via BBC Genome.

- ^ "Monica Dickens". BFI. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018.

- ^ Lauder, Afferbeck (A. A. Morrison) Let Stalk Strine, Sydney, 1965, p. 9.