Paweł Jasienica

Paweł Jasienica | |

|---|---|

Stefan Batory University | |

| Genre | history |

| Subject | Polish history |

| Notable works | Piast Poland, Jagiellonian Poland, The Commonwealth of Both Nations |

| Signature | |

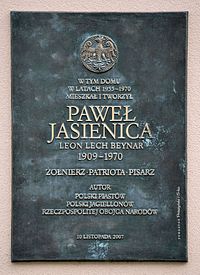

Paweł Jasienica was the pen name of Leon Lech Beynar (10 November 1909 – 19 August 1970), a Polish historian, journalist, essayist and soldier.

During

Jasienica became an outspoken critic of the

Life

Youth

Beynar was born on 10 November 1909 in

Beynar graduated from

World War II

During

Post-war

After recovering from his wounds in 1945, Beynar decided to leave the resistance, and instead began publishing in an independent Catholic weekly

Over time, he became increasingly involved in various dissident organizations.

Jasienica was, however, very outspoken in his criticism of the

Jasienica died from cancer[10] on 19 August 1970 in Warsaw. Some publicists later speculated to what extent his death was caused by "hounding from the party establishment".[14] He is buried in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery.[2] His funeral was attended by many dissidents and became a political manifestation; Adam Michnik recalls seeing Antoni Słonimski, Stefan Kisielewski, Stanisław Stomma, Jerzy Andrzejewski, Jan Józef Lipski and Władysław Bartoszewski.[10] Bohdan Cywiński read a letter from Antoni Gołubiew.[2][10]

Work

Jasienica book publishing begun with a historical book, Zygmunt August na ziemiach dawnego Wielkiego Księstwa (Sigismund Augustus in the lands of the former Grand Duchy; 1935). He is best known for his highly acclaimed

His Dwie drogi (Two ways, 1959) about the

In addition to historical books, Jasienica, wrote a series of essays about archeology – Słowiański rodowód (Slavic genealogy; 1961) and Archeologia na wyrywki. Reportaże (Archeological excerpts: reports; 1956), journalistic travel reports (Wisła pożegna zaścianek, Kraj Nad Jangtse) and science and technology (Opowieści o żywej materii, Zakotwiczeni). Those works were mostly created around the 1950s and 1960s.

His Pamiętnik (Memoirs) was the work that he began shortly before his death, and that was never completely finished.

In 2006, Polish journalist and former dissident Adam Michnik said that:

I belong to the generation '68, a generation that has special debt to Paweł Jasienica – in fact he paid with his life for daring to defend us, the youth. I want for somebody to be able to write, at some point, that in my generation there were people who stayed true to his message. Those who never forgot about his beautiful life, his wise and brave books, his terrible tragedy.[10]

Polish historian Henryk Samsonowicz echoes Michnik's essay in his introduction to a recent (2008) edition of Trzej kronikarze, describing Jasienica as a person who did much to popularize Polish history.[19] Hungarian historian Balázs Trencsényi notes that "Jasienica's impact of the formation of the popular interpretation of Polish history is hard to overestimate".[16] British historian Norman Davies, himself an author of a popular account of Polish history (God's Playground), notes that Jasienica, while more of "a historical writer than an academic historian", had "formidable talents", gained "much popularity" and that his works would find no equals in the time of communist Poland.[18] Samsonowicz notes that Jasienica "was a brave writer", going against prevailing system, and willing to propose new hypotheses and reinterpret history in innovative ways.[19] Michnik notes how Jasienica was willing to write about Polish mistakes, for example in the treatment of Cossacks.[10] Ukrainian historian Stephen Velychenko also positively commented on Jasienica's extensive coverage of the Polish-Ukrainian history.[17] Both Michnik and Samsonowicz note how Jasienica's works contain hidden messages in which Jasienica discusses more contemporary history, such as in his Rozważania....[10][19][20]

Bibliography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

Several of Jasienica's books have been translated into English by Alexander Jordan and published by the American Institute of Polish Culture, based in Miami, Florida.

- Zygmunt August na ziemiach dawnego Wielkiego Księstwa (Sigismund Augustus on the lands of the former Grand Duchy; 1935)

- Ziemie północno-wschodnie Rzeczypospolitej za Sasów (North-eastern lands of the Commonwealth during the Sas dynasty; 1939)

- Wisła pożegna zaścianek (Vistula will say farewell to gentry's province; 1951)

- Świt słowiańskiego jutra (Dawn of the Slavic tomorrow; 1952)

- Biały front (White front, 1953)

- Opowieści o żywej materii (Tales of living matter; 1954)

- Zakotwiczeni (Moored; 1955)

- Chodzi o Polskę (It's about Poland; 1956)

- Archeologia na wyrywki. Reportaże (Archeological excerpts: reports; 1956; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-085-5)

- Ślady potyczek (Traces of battles; 1957; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-196-8)

- Kraj Nad Jangtse (Country at Yangtze; 1957; latest Polish edition from 2008 uses the Kraj na Jangcy title; ISBN 978-83-7469-798-9)

- Dwie drogi (Two ways; 1959; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-89325-28-0)

- Myśli o dawnej Polsce (Thoughts about Old Poland; 1960; latest Polish edition 1990; ISBN 83-07-01957-5)

- Polska Piastów (1960; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 0-87052-134-9)

- Słowiański rodowód (Slavic genealogy; 1961, latest Polish edition 2008; ISBN 978-83-7469-705-7)

- Tylko o historii (Only about History; 1962, latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-267-5)

- Polska Jagiellonów (1963; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-1-881284-01-7)

- Trzej kronikarze (Three chroniclers; 1964; latest Polish edition 2008; ISBN 978-83-7469-750-7)

- Ostatnia z rodu (Last of the Family; 1965; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-135-7)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów (1967–1972), translated as The Commonwealth of Both Nations; 1987, ISBN 0-87052-394-5), often published in three separate volumes:

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.1: Srebrny wiek (1967; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 0-87052-394-5)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.2: Calamitatis Regnum (1967; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 1-881284-03-4)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.3: Dzieje agoni (1972; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 1-881284-04-2)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.1: Srebrny wiek (1967; latest Polish edition 2007;

- Rozważania o wojnie domowej (Thoughts on Civil War; 1978; latest Polish edition 2008)

- Pamiętnik (Diary; 1985; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-612-8)

- Polska anarchia (Polish Anarchy; 1988; latest Polish edition 2008; ISBN 978-83-7469-880-1)

Awards

- Medals:

- Order of Polonia Restituta, Grand Cross, awarded on 3 May 2007 (posthumously)[19]

- Order of Polonia Restituta, Knight's Cross, awarded on 22 July 1956

- Polish Ministry of Defensein 1967

- Home Army Cross, awarded in 1967 in London

- Awards:

- 2007 laureate of Poland's "Custodian of National Memory" Prize.[21]

See also

References

- ^ Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. 2007. Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Gadkowska, Aleksandra Gromek (2 March 2011). "Paweł Jasienica" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 16 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Żbikowski, Zbigniew (14 April 2001). "Kapitan martwej armii: Paweł Jasienica". Życie (in Polish). Archived from the original on 20 March 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8101-2203-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Prawa autorskie po Jasienicy tylko dla jego córki". Gazeta (in Polish). PAP (Polish Press Agency). 28 December 2006. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Sierocińska, Gabriela (2 December 2008). "Paweł Jasienica" (in Polish). Polskie Radio. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Kowalik, Helena. "Ubeckie donosy z sypialni" (in Polish). Helena Kowalik. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Klub Krzywego Koła – trybuna inteligencji czy barometr władzy?" (in Polish). Polskie Radio. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-86516-245-7. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Michnik, Adam (19 August 2005). "Michnik o Jasienicy: pisarz w obcęgach". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Archived from the original on 1 March 2010.

- ^ (in Polish) Szpotański, Janusz Ballada o Łupaszce. Retrieved 6 February 2017

- ^ Jezierski, Piotr. "Uwieść Jasienicę". Historia (in Polish). Polskie Radio. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009.

- ^ Łazarewicz, Cezary (12 March 2010). "Nesia wszystko doniesie" [Nesia will report everything]. Polityka (in Polish). Archived from the original on 7 August 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-520-26923-1. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-691-11306-7. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-963-7326-85-1. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-08552-0. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9.

- ^ a b c d e (in Polish) Samsonowicz, Henryk Wstęp, in Paweł Jasienica, Trzej kronikarze, 2008 edition

- ISBN 978-83-01-14227-8. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ (in Polish) Rok 2007 – Uroczystość wręczenia Nagrody Kustosz Pamięci Narodowej, ipn.gov.pl. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

Further reading

- ISBN 83-207-1492-3

- Wiaderny, Bernard Paweł Jasienica: Fragment biografii, wrzesien 1939 – brygada Łupaszki, 1945 (Paweł Jasienica: Fragment of a Biography, September 1939 – Łupaszko's Brigade, 1945); Warsaw, Antyk

- Beynar-Czeczott, Ewa Mój ojciec Paweł Jasienica (My father Paweł Jasienica); Prószyński i S-ka 2006, ISBN 83-7469-437-8)

![]() Polish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paweł Jasienica

Polish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paweł Jasienica