Naqada III

| Geographical range | Egypt |

|---|---|

| Period | Early Bronze I |

| Dates | c. 3,300 BC – 2,900 BC[1] |

| Major sites | Naqada, Tarkhan, Nekhen |

| Preceded by | Naqada II |

| Followed by | Early Dynastic Period (Egypt) |

Naqada III is the last phase of the

History

The Protodynastic Period in ancient Egypt was characterised by an ongoing process of political unification, culminating in the formation of a single state to begin the

State formation began during this era and perhaps even earlier. Various small city-states arose along the

Early Egyptologists such as Flinders Petrie were proponents of the Dynastic race theory which hypothesised that the first Egyptian chieftains and rulers were themselves of Mesopotamian origin,[3] but this view has been abandoned among modern scholars.[4][5][6][7][8]

Most

Naqada III extended all over Egypt and was characterized by some notable firsts:

- The first hieroglyphs

- The first graphical narratives on palettes

- The first regular use of serekhs

- Possibly the first example of irrigation

And at best, a notable second:

- The invention of

According to the Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities, in February, 2020, Egyptian archaeologists have uncovered 83 tombs dating back to 3,000 B.C, known as the Naqada III period. Various small ceramic pots in different shapes and some sea shells, makeup tools, eyeliner pots, and jewels were also revealed in the burial.[12][13]

Decorative cosmetic palettes

Many notable decorative palettes are dated to Naqada III, such as the Hunters Palette.

-

Hunters Palette, circa 3100 BC

-

"Four Dogs Palette" (3300–3100 BC)

-

Fragment of a ceremonial palette illustrating a man and a type of staff, ca. 3200–3100 BC

-

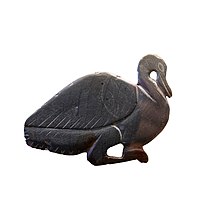

Duck-shaped palette

-

Bull Palette, 3100 BC

-

TheButo-Maadi culture, by the Egyptian rulers of Naqada III, circa 3100 BC.[14]

-

Fragment of a palette, 3200–2800 BC.

Other artifacts

-

Baboon Divinity bearing name of Pharaoh Narmer on base

-

Protodynastic sceptre fragment with royal couple. Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst, Munich

-

Hair Comb Decorated with Rows of Wild Animals 3200–3100 BCE, Naqada III

-

Naqada III vessel

-

Typical Naqada III cylindrical jar

See also

- Badarian culture

- Early Dynastic Egypt

- First Dynasty of Egypt

- List of Pharaohs

- Naqada culture

- Scorpion II

- Scorpion Macehead

References

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan. "The relative chronology of the Naqada culture: Problems and possibilities [in:] Spencer, A.J. (ed.), Aspects of Early Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1996: 36-69": 64.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Shaw 2000, p. 479.

- S2CID 194596267.

- ISBN 0415186331.

- ISBN 0807845558.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. (2007). Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state. Highfield, Southampton: Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton.

- ISBN 0936260645.

- ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9.

- ^ Shaw 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Meza, A.I. (2007) “Neolithic Boats: Ancient Egypt and the Maltese Islands. A Minoan Connection” J-C. Goyon,C. Cardin (Eds.) Actes Du Neuvième Congrès International Des Égyptologues, p. 1287.

- S2CID 162515460.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (21 February 2020). "Dozens of ancient Egyptian graves found with rare clay coffins". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- ^ "الكشف عن 83 مقبرة أثرية بمنطقة آثار كوم الخلجان بمحافظة الدقهلية". اليوم السابع. 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- ^ Brovarski, Edward. "REFLECTIONS ON THE BATTLEFIELD AND LIBYAN BOOTY PALETTES": 89.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Anđelković, Branislav (2002). "Southern Canaan as an Egyptian Protodynastic Colony". Cahiers Caribéens d'Égyptologie. 3/4 (Dix ans de hiéroglyphes au campus): 75–92.

- Bard, Katherine A. (2000). "The Emergence of the Egyptian State". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 61–88. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- Midant-Reynes, Béatrix (2000). The Prehistory of Egypt: From the First Egyptians to the First Pharaohs. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-20169-6.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- Wilkinson, Toby Alexander Howard (2001). Early Dynastic Egypt (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18633-1.

- Wright, Mary (1985). "Contacts Between Egypt and Syro-Palestine During the Protodynastic Period". S2CID 165458408.

External links

- Naqada III: Dynasty 0

- "Unification Theories", Naqadan in Egypt, UK: UCL.

![The Battlefield Palette, possibly showing the subjection of the people of the Buto-Maadi culture, by the Egyptian rulers of Naqada III, circa 3100 BC.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/The_Battlefield_Palette_3100_BC_-_Joy_of_Museums.jpg/185px-The_Battlefield_Palette_3100_BC_-_Joy_of_Museums.jpg)