User:Kavigupta/Wellness (alternative medicine)

Wellness is generally used to mean a state beyond absence of illness but rather aims to optimize well-being.[1] It is often used as an umbrella term for pseudoscientific health interventions.[2]

The notions behind the term share the same roots as the alternative medicine movement, in 19th-century movements in the US and Europe that sought to optimize health and to consider the whole person, like New Thought, Christian Science, and Lebensreform.[3][4]

History

The term was partly inspired by the preamble to the World Health Organization’s 1948 constitution which said: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”[1] It was initially brought to use in the US by Halbert L. Dunn, M.D. in the 1950s; Dunn was the chief of the National Office of Vital Statistics and discussed “high-level wellness,” which he defined as “an integrated method of functioning, which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable.”[1] The term "wellness" was then adopted by John Travis who opened a "Wellness Resource Center" in Mill Valley, California in the mid-1970s, which was seen by mainstream culture as part of the hedonistic culture of Northern California at that time and typical of the Me generation.[1] Travis marketed the center as alternative medicine, opposed to what he said was the disease-oriented approach of medicine.[1] The concept was further popularized by Robert Rodale through Prevention magazine, Bill Hetler, a doctor at University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, who set up an annual academic conference on wellness, and Tom Dickey, who established the Berkeley Wellness Letter in the 1980s.[1] The term had become accepted as standard usage in the 1990s.[1]

In recent decades, while there were magazines devoted to wellness, it was noted that mainstream news sources had begun to devote more page space to "health and wellness themes".[5]

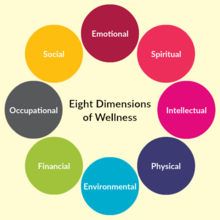

The US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration uses the concept of wellness in its programs, defining it as having eight aspects: emotional, environmental, financial, intellectual, occupational, physical, social, and spiritual.[6]

Corporate wellness programs

By the late 2000s the concept had become widely used in

Criticism

Promotion of Pseudoscience

Wellness is a particularly broad term,

Healthism

Wellness has also been criticized for its focus on lifestyle changes over a more general focus on harm prevention that would include more establishment-driven approaches to health improvement such as accident prevention.[3] Petr Skrabanek has also criticized the wellness movement for creating an environment of social pressure to follow its lifestyle changes without having the evidence to support such changes.[9] Some critics also draw an analogy to Lebensreform, and suggest that an ideological consequence of the wellness movement is the belief that "outward appearance" is "an indication of physical, spiritual, and mental health."[10]

The wellness trend has been criticised as a form of conspicuous consumption.[11]

See also

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Healthism

- Organic food culture

- Salutogenesis

- Wellness tourism

- Workplace wellness

Reference

- ^ a b c d e f g Zimmer, Ben (2010-04-16). "Wellness". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Freeman, Hadley. "Pseudoscience and strawberries: 'wellness' gurus should carry a health warning". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ PMID 25037836.

- ^ Blei, Daniela (4 January 2017). "The False Promises of Wellness Culture". JSTOR Daily.

- PMID 14695358.

- ^ "The Eight Dimensions of Wellness". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2016.

- ^ a b c Larocca, Amy. "The Wellness Epidemic". The Cut. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Appleyard, Bryan (21 September 1994). "Healthism is a vile habit: It is no longer enough simply to be well; we are exhorted to pursue an impossible and illiberal cult of perfection". Independent. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Blei, Daniela (2017-01-04). "The False Promises of Wellness Culture". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- ^ Bearne, Suzanne (1 September 2018). "Wellness: just expensive hype, or worth the cost?". the Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2018.