Wolfsburg Castle

| Wolfsburg Castle | |

|---|---|

Schloss Wolfsburg, Burg Wolfsburg | |

| Wolfsburg | |

The Wolfsburg (southwest side) | |

| Coordinates | 52°26′21″N 10°47′58″E / 52.43917°N 10.79944°E |

| Type | lowland castle |

| Code | DE-NI |

| Site information | |

| Condition | converted to a Renaissance palace |

| Site history | |

| Built | first mentioned 1302 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | nobility |

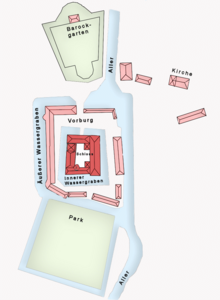

The Wolfsburg is a medieval lowland and water castle in North Germany that was first mentioned in the records in 1302, but has since been turned into a Renaissance schloss or palace. It is located in eastern Lower Saxony in the town of Wolfsburg named after it and in whose possession it has been since 1961. The Wolfsburg developed from a tower house on the River Aller into a water castle with the character of a fortification. In the 17th century it was turned into a representative, but nevertheless defensible palace that was the northernmost example of the Weser Renaissance style. Its founder and builder was the noble family of von Bartensleben. After their line died out in 1742 the Wolfsburg was inherited by the counts of Schulenburg.

Name

The name Wolfsburg (literally "Wolf Castle") does not indicate that the region of the

Design

Main structure

Since the 17th century the castle has been a four-sided, solid building surrounding an inner courtyard. The main body of the castle thus has four wings, which are named after the points of the compass. The upper outline of the castle with its finely decorated cross-gables,

Entrance

Outsize stone figures on horseback decorate the palace entrance with its round arch. Above the portal there are stone shields with the coat of arms of the Bartenslebens,

Bergfried

The bergfried is integrated as an element of the west wing into the main structure and is recognisable as such by its lack of decoration and windows. The tower has an area of 9 x 9 metres, a height of around 23 metres and wall thickness of up to 3 metres. It is the oldest part of the whole site and its origins may go back to the 13th century.

Towers

In the internal corners of the courtyard there are three other towers with staircases that enable the individual floors to be accessed. These are the Watchman's Tower (Hausmannsturm) which at around 30 metres is the highest, the Owl Tower (Uhlenturm) and the hexagonal Wendelstein tower with its

Wings

The north and south wings from the 16th century were mainly used for residential purposes. The roughly 25 metre high east wing was completed at the beginning of the 17th century. With its splendid decorative shapes in the

History

Foundation

The reason for the construction of the Wolfsburg was the

Middle Ages and Early Modern Period

During the

The Wolfsburg emerged from the Thirty Years' War as one of the few aristocratic castles that remained undestroyed. It was almost continuously garrisoned by troops of the warring parties, the last being the Swedes. The lords of Brunswick and Magdeburg forced their withdrawal came in 1650 by having the castellans have the fortifications slighted. Six years later the von Bartenslebens had the fortifications rebuilt because they wanted to retain the military character of the castle.

Construction history

Medieval castle

In the early stages around 1300 the Wolfsburg only had a stone

Due to its situation in the

Weser Renaissance palace

In the middle of the 15th century, a medieval castle no longer reflected the status of the von Bartenslebens. They turned the less comfortable building into a showy palace in the Weser Renaissance style with gardens and parks. Nevertheless, it retained the character of a fortified water castle until 1840, when the protective moats were filled in as the Aller river was artificially confined and controlled.

In 1574, thanks to his great fortune,

Hans the Wealthy had the Red House (Rotes Haus), a section of the building that had fallen into disrepair, demolished and erected in its place the present north wing with the entranceway to the schloss. When he died in 1583, his relative Günzel, his brother Günther and their uncle Jakob continued the work and built the ostentatious east wing. Then followed the south wing as the Palas with its Great Hall. Not until 1620 was the palace completed in its present shape as a four-winged building with enclosed courtyard and outside dimensions of 50 x 60 metres.

In converting it into a Renaissance palace, architecture and ornamentation were influenced by the Weser Renaissance style, of which the Wolfsburg is a typical example, as well as the most northeasterly one. The builders, stonemasons and sculptors who took part had also been involved in building palaces in the Weser region, for example, the Hamelin builder, Johann Edeler (also: Johann von der Mehle).

Literature

- Johannes Zahlten: Schloss Wolfsburg – Ein Baudenkmal der Weserrenaissance. Braunschweig 1991, ISBN 3-925151-52-4

- Schloss Wolfsburg – Geschichte und Kultur. Stadt Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg 2002, ISBN 3-930292-62-9

- Historisch-Landeskundliche Exkursionskarte von Lower Saxony, Blatt Wolfsburg. S. 145, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für historische Landesforschung der Universität Göttingen, Hildesheim 1977, ISBN 3-7848-3626-7

- Hans Adolf Schultz: Burgen und Schlösser des Braunschweiger Landes. Braunschweig 1980, ISBN 3-87884-012-8

External links

- Photo series of the castle from 2002–2005 with floor plan, baroque gardens, park, garden exhibitions, etc. (in German)

- Description and photos on the Brunswick-Eastphalia Region site (in German)

- Wolfsburg's "Town Museum in the Castle" (in German)

- The Wolfsburg in the Middle Ages (in German)

- The castle becomes a palace (in German)

- Description and photographs at burgerbe-Weblog (in German)

- Panoramic photograph of the castle courtyard (in German)