Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung

| |

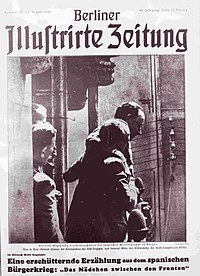

Cover of issue of 26 August 1936: first meeting between Francisco Franco and Emilio Mola | |

| Frequency | weekly |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1891 |

| First issue | 4 January 1892 |

| Final issue | 1945 |

| Company | Ullstein Verlag |

| Country | Germany |

| Based in | Berlin |

| Language | German |

The Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, often abbreviated BIZ, was a German weekly illustrated magazine published in Berlin from 1892 to 1945. It was the first mass-market German magazine and pioneered the format of the illustrated news magazine.

The Berliner Illustrirte was published on Thursdays but bore the date of the following Sunday.[1]

History

The magazine was founded in November 1891

Once it no longer required a subscription, the Berliner Illustrirte fundamentally changed the newspaper market, attracting readers by its appearance, particularly the eye-catching pictures. The first cover created a sensation, featuring a group portrait of officers who had been killed in a shipwreck. Initially it was illustrated with engravings, but it soon embraced photographs. Beginning in 1901, it was also technically feasible to print photographs inside the magazine, a revolutionary innovation. Building on the example of a rival Berlin publication, August Scherl's Die Woche, Ullstein developed it into the prototype of the modern news magazine.[5] It pioneered the photo-essay,[5][9] had a specialised staff and production unit for pictures and maintained a photo library.[4] With other news magazines like the Münchner Illustrierte Presse in Munich and Vu in France, it also pioneered the use of candid photographs taken with the new smaller cameras.[10] In August 1919, a cover photograph of the German President Friedrich Ebert and Minister of Defence Gustav Noske on holiday on the Baltic coast, clad in swimming trunks, caused heated debate about propriety; within a decade, such informality would seem normal.[11] Kurt Korff (Kurt Karfunkelstein), then the editor in chief, pointed out in 1927 the parallel with the rise of the cinema, another aspect of the increasing role of "life 'through the eyes'".[12] He and publishing director Kurt Szafranski sought out reporters who could tell a story using photographs, notably the pioneer sports photographer Martin Munkácsi, the first staff photographer at a German illustrated magazine,[13][14] and Erich Salomon, one of the founders of photo-journalism.[15] After initially working in advertising for Ullstein, Salomon signed an exclusive contract with the Berliner Illustrirte as a photographer and contributed both inside shots of meetings of world leaders[10][16][17] and photo-essays on the strangeness of life in the US, for example eating at automats (for which he used staged photographs depicting himself being schooled in how it was done).[18]

The magazine also strove for the most up-to-the-minute coverage possible, beginning in 1895 when a photograph from a fire was submitted; the engineer who had taken it was encouraged to provide more news photographs and a few weeks later founded the photography firm of Zander & Labisch.[19] In April 1912, the presses were stopped when the news came in of the sinking of RMS Titanic, and a half-page photo of the Acropolis was replaced with one of the ship.

The Berliner Illustrirte also featured drawings. The cover image of the 23 April 1912 issue was an allegorical drawing of the iceberg which claimed the Titanic as death,[20][21] and the strip cartoon Vater und Sohn by E. O. Plauen (Erich Ohser) was the most popular in 1930s Germany.[22] In the 1910s, the magazine awarded a prize for the year's best drawing, the Menzelpreis, presumably named for Berlin artist Adolph Menzel. Winners included Fritz Koch and Heinrich Zille.[23][24]

In 1928, when it was the largest weekly in Europe by circulation, the magazine published Vicki Baum's novel of the New Woman, Stud. chem. Helene Willfüer, in serial form. It provoked heated discussions and required repeated increases in the print runs until they exceeded 2 million.[25]

Appeal to the common reader also included competitions; for example, in May–June 1928, a contest called Büb oder Mädel offered prizes to readers who could correctly identify the sex of young people in six photographs.[26]

The magazine was publishing a million copies by 1914[4] and 1.8 million by the end of the 1920s;[27] in 1929, it was the only German magazine to approach the circulation numbers of the large American weeklies.[28] In 1931, its circulation was almost 2 million: 1,950,000.[29] Meanwhile, that of the rival Die Woche had fallen from 400,000 in 1900 to 200,000 in 1929.[30] From 1926 to 1931, news periodicals in Germany had their own aircraft deliver copies to remote places; Luft Hansa then took over this function.

Under the

After the war, the Ullstein family regained control of the publishing company but beginning in 1956, gradually sold it to

References

- ISBN 9783550074967) (in German)

- ISBN 978-1-84545-087-8. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 103.

- ^ ISBN 9780191557293, p. 30.

- ^ ISBN 9781571132055, p. 53.

- ^ ISBN 9783525207918, p. 73(in German)

- ^ de Mendelssohn, pp. 104–08.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 256.

- ISBN 9780810905597, p. 235.

- ^ ISBN 9781606060223, p. 6.

- ISBN 9780253347183, p. 225.

- , and de Mendelssohn, p. 112.

- ISBN 9780719058042, pp. 73–80, p. 75.

- ^ Maria Morris Hambourg, "Photography between the Wars: Selections from the Ford Motor Company Collection", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin N.S. 45.4, Spring 1988, pp. 5–56, p. 17.

- ].

- ^ Marien, p. 237.

- ISBN 9780271054223, p. 124.

- ISBN 9781584655961, pp. 64–65.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 109.

- ISBN 9783379017121, p. 28(in German)

- ^ "Die erste Nachricht über den Untergang der 'Titanic'", Medienpraxis blog, 15 April 2012 (in German), with image.

- (in German)

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 111.

- ^ Die Kunst für Alle 26 (1911) p. 86 (in German)

- ISBN 9783412097011, p. 65(in German). The novel was published in English translation as Helene.

- ^ Maud Lavin, "Androgyny, Spectatorship, and the Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch", New German Critique 51, Autumn 1990, pp. 62–86, p. 75.

- .

- ^ Ross, p. 147.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 304.

- OCLC 719369972, p. 14, note.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, pp. 364–66.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 393.

- ^ Ross, p. 362.

- ISBN 9783412204433, p. 363(in German)

- ^ Deák, p. 40.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 112.

- ISBN 9783638673303, note 19(print on demand) (in German)

- ISBN 9781859734001, p. 441.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, pp. 414–15.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 417.

- ^ Hempfling, n.p.

- ^ "Berliner Illustrirte: Die Fahne hoch", Der Spiegel issue 7, 1961 (in German).

Further reading

- Christian Ferber. Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. Zeitbild, Chronik, Moritat für Jedermann 1892–1945. Berlin: Ullstein, 1982. ISBN 9783550065866. (in German)

- Wilhelm Marckwardt. Die Illustrierten der Weimarer Zeit: publizistische Funktion, ökonomische Entwicklung und inhaltliche Tendenzen (unter Einschluss einer Bibliographie dieses Pressetypus 1918–1932). Minerva-Fachserie Geisteswissenschaften. Munich: Minerva, 1982. ISBN 9783597101336(in German)

External links

- Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung 1925, 1935, 1936, digitised at Fulda University of Applied Sciences

- Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung 1941, digitised at Fulda University of Applied Sciences

- Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung 1915,1917, digitised at Bibliothèque nationale de France