Chaïm Soutine

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Chaïm Soutine | |

|---|---|

École de Paris, Expressionism | |

| Patron(s) | |

| Signature | |

Chaïm Soutine (Russian: Хаим Соломонович Сутин, Khaïm Solomonovitch Sutin;

Inspired by classic painting in the European tradition, exemplified by the works of

Early life

Soutine was born Chaim-Iche Solomonovich Sutin, in

Early life and arrival in Paris

La Ruche and Montparnasse

For a time, he and his friends lived at La Ruche, a residence for struggling artists in Montparnasse in Paris. Since 1900, the Montparnasse district, popularized by Apollinaire, had supplanted Montmartre as the epicenter of an intellectual and artistic life in Paris. It was the meeting place of writers, painters, sculptors, actors, often struggling financially, who exchanged and created art and literature whilst sitting and chatting in cafes.[7]

La Ruche, whose rotunda stands on Dantzig Passage in the 15th arrondissement, not far from Montparnasse, a cosmopolitan commune where painters and sculptors from all over, many from Eastern Europe, rented small studios at a low cost. There Soutine encountered, among others, Archipenko, Zadkine, Brancusi, Chapiro, Kisling, Epstein, Chagall, Chana Orloff, as well as Lipchitz who introduced Amadeo Modigliani to Soutine.[8]

The two became friends. Modigliani painted Soutine's portrait several times, most famously in 1917, on a door of an apartment belonging to Léopold Zborowski, who was their art dealer.[9] Until he acquired his own studio, he slept and worked at various places, specifically at Krémègne and Kikoïne's, fellow Jewish painters of the School of Pairs. His poverty was such he even slept in stairways and on benches.[10]

Upon his arrival in Paris, Soutine eagerly immersed himself in his exploration of the French capital. "In a filthy hole like Smilovitchi," he claimed, where, he also said, they are unaware of the existence of a piano, "one cannot imagine that there are cities like Paris, or music like that of Bach." As soon as he has a few pennies in his pocket, he would spend them in order to "immerse himself" in music at Colonne or Lamoureux concerts, with a preference Baroque music.[11] He haunted the galleries of the Louvre, either hugging the walls or jumping at the slightest approach, and contemplated for hours his favorite painters: "if he loves Fouquet, Raphael, Chardin, and Ingres, it is especially in the works of Goya and Courbet, and more than any other, in those of Rembrandt, that Soutine recognizes himself." Chana Orloff recounted that, seized by a "respectful fear" in front of a Rembrandt, he could also go into ecstasy and exclaim, "It's so beautiful that it drives me mad!".[12]

Soutine took French lessons, often in the back of La Rotonde, managed at the time by Victor Libion. Libion, who acted as a sort of artists' patron, allowed artists to warm up from the cold in La Rotonde and discuss for hours without requiring them to make additional purchases. After learning French Soutine an avid reader of Russian novels also began to enthusiastically read and immerse himself in French literature, reading Balzac, Baudelaire, or Rimbaud, and later, Montaigne.[13]

Zborowski supported Soutine through World War I, taking the struggling artist with him to

The Interwar period

After the war Paul Guillaume, a highly influential art dealer, began to champion Soutine's work. In 1923, in a showing arranged by Guillaume, the prominent American collector Albert C. Barnes, bought 60 of Soutine's paintings on the spot. Soutine, who had been virtually penniless in his years in Paris, immediately took the money, ran into the street, hailed a Paris taxi, and ordered the driver to take him to Nice, on the French Riviera, more than 400 miles away.

Céret

Soutine lived for several years in the Midi, initially between Vence and Cagnes-sur-Mer, then, abandoning the French Riviera for the Pyrénées-Orientales in 1919, specifically for Céret. Regardless of his frequent trips to Paris—particularly in October 1919 to obtain his identity card, mandatory for foreigners— there he changed residences and studios several times.[14] One of his places of residence was the Maison Laverny, 5 rue de l'hôpital (rue Pierre Rameil). There Soutine was nicknamed by the locals as "el pintre brut" ("the dirty painter"), due to his miserable living conditions on allowances from Zborowski.[15]

During a visit to the Midi, Zborowski wrote to a friend regarding Soutine: "He gets up at three in the morning, walks twenty kilometers loaded with canvases and colors to find a site he likes, and goes back to bed forgetting to eat. But he unfastens his canvas and, having spread it on the one from the day before, he falls asleep next to it" - Soutine indeed only owned one canvas. The locals took pity at times and at times sympathized with the painter. Soutine painted portraits of the locals, in his works alluding to certain famous series such as those of men in prayer or pastry chefs and café boys, whom he represented facing forward, their working hands often disproportionately depicted. Between 1920 and 1922, he painted around two hundred canvases there.[16][17][18]

Although Soutine eventually grew to dislike the place and the works he created there, this period is generally considered a key stage in the evolution of his art. Soutine's art at the period is no longer hesitatent, "inject his own emotions into the subjects and figures of his paintings."[19] Especially, he imparts extreme deformations to the landscapes, carrying them away in a "rotary movement" already perceived by Waldemar-George in still lifes:[20] under the pressure of internal forces that seem to compress them, the forms spring forth twisting, and the masses rise "as if caught in a maelstrom" as described by Jover.[19]

Carcass paintings

Soutine once horrified his neighbors by keeping an animal carcass in his studio so that he could paint it (Carcass of Beef). The stench drove them to send for the police, whom Soutine promptly lectured on the relative importance of art over hygiene. There's a story that

Between Paris and Midi

By 1926, five of Soutine's paintings were sold at Drouot for amounts ranging from 10,000 to 22,000 francs.[22] However, this did not prevent him from boycotting the opening in June 1927 of the first exhibition of his works by Henri Bing in Bing's gallery on Rue La Boétie.[23] On the other hand, he reportedly eagerly accepted the opportunity to create set designs for a ballet by Diaghilev—a project that never materialized due to the sudden death of the impresario in 1929.

German invasion

Soon afterwards France was invaded by German troops. As a

There, despite intense stomach burns that soon forced him to subsist solely on porridge, the painter resumed his work, supplied with canvases and colors by the painter Marcel Laloë.[24] The landscapes from the years 1941-1942 seem to have abandoned warm tones, such as the Landscape of Champigny. The The Big Tree painted in Richelieu strained Soutine's relationship with the Castaings as he reduced the canvas size before delivering it to them.[25] However, he also tackled new and lighter subjects like The Pigs or The Return from School after the Storm. He also created portraits of children and more serene maternity scenes.[26]

Illness and death

Suffering from a stomach ulcer and bleeding badly, Soutine left a safe hiding place for Paris for emergency surgery, which failed to save his life. On 9 August 1943, he died of a perforated ulcer. He was interred in

Legacy

In February 2006, an oil painting of his controversial and iconic series Le Bœuf Écorché (1924) sold for a record £7.8 million ($13.8 million) to an anonymous buyer at a Christie's auction held in London—after it was estimated to fetch £4.8 million. In February 2007, a 1921 portrait of an unidentified man with a red scarf (L'Homme au Foulard Rouge) sold for $17.2 million—a new record—at Sotheby's London auction house.

One of the beef paintings, known as Le bœuf, circa 1923, was sold for $1 million in 2004 and resold six months later for twice that price to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Heirs of the first seller sued to have the painting returned, claiming the price was unfairly low, and a complex settlement in 2009 required the painting to be transferred to them.[27] In May 2015, Le Bœuf achieved a record price for the artist of $28,165,000 at the Christie's curated auction Looking forward to the past.[28]

Roald Dahl placed him as a character in his 1952 short story "Skin".[29]

The Jewish Museum in New York has presented major exhibitions of Soutine's work in An Expressionist in Paris: The Paintings of Chaim Soutine[30] (1998) and Chaim Soutine: Flesh (2018).[31]

In 2020, Soutine's painting Eva became a symbol of pro-democracy protests in Belarus.[32][33]

Artistic Style

"Expression is in the touch" declared Soutine, meaning expression is found in the movement in the rhythm and the passion applied by the pencil against the surface of the canvas.[34] It is said Soutine rapidly moved from linear and rigid drawing of his still life in order to discover "his true element, the touch of color and its sinuous bending".[35][34]

Gallery

Portraits and figures

-

Self Portrait (1918) oil on canvas, 21.5 × 18 in., Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection, on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

The Idiot (c. 1920) oil on canvas, 36.2 × 25.5 in., Calvet Museum, Avignon

-

Farm Girl (1922) oil on canvas, 31.5 × 17.5 in., collection unknown

-

The Little Pastry Chef (1922–23) oil on canvas, 73 × 54 cm, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

-

Woman in Pink (c. 1924) oil on canvas, 73 × 54.3 cm., Saint Louis Art Museum

-

Portrait Of A Man With A Felt Hat (1924) oil on canvas, 36 × 28 in., collection unknown

-

The Floor Waiter (Le Garçon d'étage) (1927) Collection Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

-

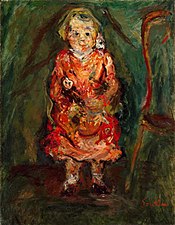

Young Girl with a Doll (1926–1927) oil on canvas, 25.5 × 19.5 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

Portrait of Madeleine Castaing (c. 1929) oil on canvas, 100 × 73 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Female Nude (1933) oil on canvas, 18 × 10.5 in., collection unknown

-

The Cook (Women in Blue) (c. 1935) oil on canvas, Museo Botero

-

Portrait d'homme (Èmile Lejeune) (1922-1923), Musée de l'Orangerie

Still Lifes

-

The Table (c. 1923) oil on canvas, 35.8 x 39.3 in., Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

-

Still Life with Rayfish (c. 1924) oil on canvas, 32 × 39.5 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Still life with Pheasant (c. 1924) oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

-

Chicken Hung Before a Brick Wall (1925) oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland

-

The Plucked Chicken (c. 1925), oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

-

Hanging Turkey (c. 1925) oil on millboard, dimensions unknown,

-

Carcass of Beef (c. 1925), oil on canvas, 53 × 32 in., Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

Landscapes

-

Chemin de la Fontaine des Tins at Céret, c. 1920, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

Chemin de la Fontaine Fils à Céret (1920) details unknown

-

View of Céret (c. 1921–22) oil on canvas, Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

Steeple of Saint-Pierre at Céret, c. 1922, Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

Landscape with Figures-Céret (1922) oil on canvas, dimensions unknown, High Museum of Art, Atlanta

-

View of Cagnes (c. 1924 –25) oil on canvas, 23.7 × 28.8 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Return From School After the Storm (c. 1939) oil on canvas, 18 × 19.75 in., The Phillips Collection, Washington, D. C.

See also

- School Of Paris

- Amedeo Modigliani

- Marc Chagall

- Isaac Frenkel Frenel

- Jules Pascin

- Michel Kikoine

- Paris

Footnotes

- ^ Getty Research Institute: Union List of Artist Names Online. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Kleeblatt, 13

- ^ By Norman Kleeblatt, September 14, 2018, Hyperallergic

- ^ "Sarah Sutina". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "Salomon Sutin". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Giraudon, Colette (2003). "Soutine, Chaïm". Grove Art Online.

- La Rotonde. (FR)

- ^ Tuchman, Dunow & Perls 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Kleeblatt et al., 101

- ^ Parisot 2005, p. 204.

- ^ Nicoïdski 1993, p. 55.

- ^ Breton 2007, p. 34.

- ^ "Chaim SOUTINE". Bureau d’art Ecole de Paris. 4 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Nicoïdski 1993, p. 114-115.

- ^ "Chaïm Soutine". Musée d'art moderne de Ceret.

- ^ Nicoïdski 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Connaissance des Arts, « Repères chronologiques », SFPA, hors-série No. 341, 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Renault 2012, p. 64.

- ^ a b Jover 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Breton 2007, p. 45.

- ISBN 978-0-7139-9652-4.

- ^ Giraudon 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Breton 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Renault 2012, p. 140-141.

- ^ Renault 2012, p. 142.

- ^ Jover 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Mitchell Martin (1 June 2009). "Soutine Suit Settled Over Bargain Beef". ArtInfo. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Chaim Soutine (1893-1943) Le Bœuf".

- ^ "Skin". 30 November 2015.

- ^ "An Expressionist in Paris: The Paintings of Chaim Soutine". The Jewish Museum. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Chaim Soutine: Flesh". The Jewish Museum. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Eva. How Most Expensive Painting In Belarus Became Symbol Of Protest". BelarusFeed. 9 July 2020. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "How Eva, a $1.8 million Portrait, Became a Symbol of Protest". Bloomberg.com. 29 June 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ a b Esti Dunow et Maurice Tuchman, « », Catalogue de l'exposition « Chaïm Soutine, l'ordre du chaos », Hazan, 2012

- ^ Marie-Madeleine Massé, , Paris, Gallimard, 2012, 48 p., ill. en coul. (ISBN 9782070138715)

References

- Breton, Jean-Jacques (2007). "Soutine ou le lyrisme désespéré". L'Estampille/L'Objet d'Art (34 (Special issue)). Faton. ISBN 9782878441819.

- Giraudon, Colette (2012). "Soutine, ses marchands, ses mécènes". Catalogue de l'exposition " Chaïm Soutine, l'ordre du chaos ". Hazan.

- Jover, Manuel (2007). "Matières sensibles". Connaissance des Arts (341 (special issue)). SFPA.

- Kleeblatt, Norman L.; Kenneth E. Silver (1998). An Expressionist in Paris: The Paintings of Chaim Soutine. New York City: Prestel. ISBN 3-7913-1932-9.

- Mullin, Rick (2012). Soutine: A Poem. Loveland, Ohio: ISBN 978-1-933675-68-8.

- Nicoïdski, Clarisse (1993). Soutine ou la profanation. Paris: ISBN 2-7096-1214-3.

- Renault, Olivier (2012). Rouge Soutine. La Petite vermillon. Paris: La Table Ronde. ISBN 9782710369868.

- Parisot, Christian (2005). Modigliani. Folio biographies. Paris: Folio. pp. 203–206 and 308. ISBN 9782070306954.

- Tuchman, Maurice; Chaim Soutine (1893–1943) , Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1968

- Tuchman, Maurice; Esti Dunow (1993) Chaim Soutine (1893–1943): catalogue raisonné. Köln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag.

- Tuchman, Maurice; Dunow, Esti; Perls, Klaus (2001). Soutine. Catalogue raisonné. ISBN 9783822816295.

- Chaïm Soutine and his Contemporaries: from Russia to Paris, Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, 2012, ISBN 978 0900 157 400

- Soutine: The power and the fury of an eccentric genius by Stanley Meisler [1]

- Ifkovic, Ed. Soutine in Exile: A Novel. Createspace, 2017.

- Chaïm Soutine, documentary film by Valérie Firla, written by Valérie Firla and Murielle Levy, 52 min, Les Productions du Golem, Ed. Réunion des musées nationaux, broadcast in France in 2008 [2].