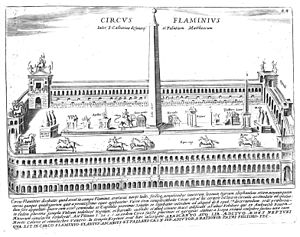

Circus Flaminius

The Circus Flaminius was a large, circular area in

Topography and structures

In its early existence, the Circus was a loop, approximately 500 meters in length stretching across the Flaminian Fields (Prata Flaminia).

During the 2nd century BC, this broad space was encroached upon by buildings and monuments. The circus had no permanent seating, nor were there any permanent structures to mark the perimeter of the race track. By the early 3rd century AD, the only open space that remained was a small piazza in the center, no more than 300 meters long, where the ludi (public games) had always been held.

There were many structures in the vicinity of the circus (“in circo Flaminio”). The

The temple of Apollo "in circo" acquired special significance under Augustus, as a popular legend developed that he had been sired by the god while his mother Atia was visiting the temple.[7] Augustus undertook myriad new constructions around the Circus, and probably had it paved for the first time. Most notably Augustus demolished the small theater dedicated to Apollo, as well as the temples of Diana and Pietas, to build the Theatre of Marcellus on the eastern side of the Circus.[8] Augustus also built the Porticus Octaviae, which hemmed in the Circus on its northeastern side.[9] Augustus' relation Lucius Marcius Phillipus restored the Temple of Hercules Musarum with a surrounding portico that could be accessed from the Circus.[8]

In AD 15, statues to the deified Augustus were erected, dedicated by

Location

Beginning in the Renaissance, the Circus Flaminius was identified with the ancient arcades facing onto the Via delle Botteghe Oscure ("Street of Dark Shops"), so-called because in the Middle Ages the arcades had sheltered the workshops of artisans. This placed the Circus north of the porticus Phillipi between the Piazza Paganica and Piazza Margana.

A previously disregarded reference in the Mirabilia Urbis Romae ("Circus Flammineus Ad Pontem Ludeorum"), which placed it near the Pons Fabricius, and a fragment of the Marble Plan labelled "CIR FLAM" which fitted south of the Portico of Octavia, confirmed the Circus to be roughly located between the Tiber to the south and the Porticos of Octavia and Phillipus to the north, and hemmed in by the Theatre of Marcellus to the east.[11][14]

Use

The Circus Flaminius was never meant to rival the much larger

The Circus also hosted ceremonies related to the

According to

The Circus Flaminius was also used as a market. Assemblies were often held within it. In 9 BC, it was the venue where Augustus delivered the Laudatio of Drusus.

Later history

The buildings remained in use until the end of the fourth century, when the area was finally abandoned. In the Middle Ages the ruins of the

In 1555, Pope Paul IV formed the Jewish Ghetto in the area encompassing much of the former Circus Flaminius. The Great Synagogue of Rome stands roughly where the southern end of the arena was located.[9]

See also

References

- ^ Pier Luigi Tucci, 'Nuove ricerche sulla topografia dell’area del circo Flaminio’, Studi Romani 41 (1993) 229-242

- ISBN 978-0-520-04921-5.

- ^ Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. pp. 493–495.

- ^ Varro, De Lingua Latina, 5.153

- ^ Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. pp. 498–500.

- ^ Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. p. 507.

- ^ a b Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. p. 506.

- ^ a b Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. pp. 510–511.

- ^ a b Peter Aicher (2004). Rome Alive: A Source Guide to the Ancient City, Vol. 1. Bolchazy-Carducci.

- ^ Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. p. 515.

- ^ a b c "The Urban Legacy of Ancient Rome". Stanford.edu. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- S2CID 163195883.

- ^ Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton University Press. p. 500.

- ^ "Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project". formaurbis.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- T.P. Wiseman, Remus: A Roman Myth (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 211

- Varro, De lingua latina 5.154; also recorded by the Fasti Ostienses.

- ^ Cassius Dio Roman History 55.10

- ^ Plutarch, Parallel Lives; XXX.II

Sources

- Platner, Samuel(1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press.

- Civilization of the ancient Mediterranean: Greece and Rome. Vol. II. Scribner's. 1998.

- Humphrey, John (1986). Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Butler & Tanner Ltd. pp. 540–545. ISBN 0-520-04921-7.