Climate of Uranus

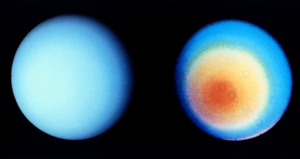

The climate of Uranus is heavily influenced by both its lack of internal heat, which limits atmospheric activity, and by its extreme axial tilt, which induces intense seasonal variation. Uranus's atmosphere is remarkably bland in comparison to the other giant planets which it otherwise closely resembles.[1][2] When Voyager 2 flew by Uranus in 1986, it observed a total of ten cloud features across the entire planet.[3][4] Later observations from the ground or by the Hubble Space Telescope made in the 1990s and the 2000s revealed bright clouds in the northern (winter) hemisphere. In 2006 a dark spot similar to the Great Dark Spot on Neptune was detected.[5]

Banded structure, winds and clouds

The first suggestions of bands and weather on Uranus came in the 19th century, such as an observation in March and April 1884 of a white band circling partially around Uranus's equator, only two years after Uranus's "spring" equinox.[6]

In 1986

In addition to large-scale banded structure, Voyager 2 observed ten small bright clouds, most lying several degrees to the north from the collar.[3] In all other respects Uranus looked like a dynamically dead planet in 1986. However, in the 1990s the number of observed bright cloud features grew considerably.[1] The majority of them were found in the northern hemisphere as they started to become visible.[1] The common though incorrect explanation of this fact was that bright clouds are easier to identify in its dark part, whereas in the southern hemisphere the bright collar masks them.[10] Nevertheless, there are differences between the clouds of each hemisphere. The northern clouds are smaller, sharper and brighter.[11] They appear to lie at a higher altitude, which is connected to fact that until 2004 (see below) no southern polar cloud had been observed at the wavelength 2.2 micrometres,[11] which is sensitive to the methane absorption, whereas northern clouds have been regularly observed in this wavelength band. The lifetime of clouds spans several orders of magnitude. Some small clouds live for hours, whereas at least one southern cloud has persisted since the Voyager flyby.[1][4] Recent observation also discovered that cloud-features on Uranus have a lot in common with those on Neptune, although the weather on Uranus is much calmer.[1]

Uranus Dark Spot

The dark spots common on Neptune had never been observed on Uranus before 2006, when the first such feature was imaged.[12] In that year observations from both Hubble Space Telescope and Keck Telescope revealed a small dark spot in the northern (winter) hemisphere of Uranus. It was located at the latitude of about 28 ± 1° and measured approximately 2° (1300 km) in latitude and 5° (2700 km) in longitude.[5] The feature called Uranus Dark Spot (UDS) moved in the prograde direction relative Uranus's rotation with an average speed of 43.1 ± 0.1 m/s, which is almost 20 m/s faster than the speed of clouds at the same latitude.[5] The latitude of UDS was approximately constant. The feature was variable in size and appearance and was often accompanied by a bright white cloud called Bright Companion (BC), which moved with nearly the same speed as UDS itself.[5]

The behavior and appearance of UDS and its bright companion were similar to Neptunian

The emergence of a dark spot on the hemisphere of Uranus that was in darkness for many years indicates that near equinox Uranus entered a period of elevated weather activity.[5]

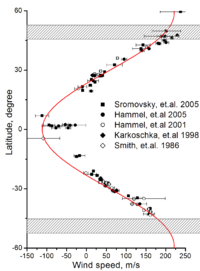

Winds

The tracking of numerous cloud features allowed determination of zonal winds blowing in the upper

Seasonal variation

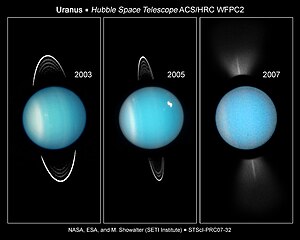

Determining the nature of this seasonal variation is difficult because good data on Uranus's atmosphere has existed for less than one full Uranian year (84 Earth years).[15] A number of discoveries have however been made. Photometry over the course of half a Uranian year (beginning in the 1950s) has shown regular variation in the brightness in two spectral bands, with maxima occurring at the solstices and minima occurring at the equinoxes.[16] A similar periodic variation, with maxima at the solstices, has been noted in microwave measurements of the deep troposphere begun in the 1960s.[17] Stratospheric temperature measurements beginning in the 1970s also showed maximum values near 1986 solstice.[18]

The majority of this variability is believed to occur due to changes in the viewing

However, there are some reasons to believe that seasonal changes are happening in Uranus. Although Uranus is known to have a bright south polar region, the north pole is fairly dim, which is incompatible with the model of the seasonal change outlined above.

The mechanism of physical changes is still not clear.

For a short period in the second half of 2004, a number of large clouds appeared in the Uranian atmosphere, giving it a

Circulation models

Several solutions have been proposed to explain the calm weather on Uranus. One proposed explanation for this dearth of cloud features is that Uranus's

Another hypothesis states that when Uranus was "knocked over" by the supermassive impactor which caused its extreme axial tilt, the event also caused it to expel most of its primordial heat, leaving it with a depleted core temperature. Another hypothesis is that some form of barrier exists in Uranus's upper layers which prevents the core's heat from reaching the surface.[24] For example, convection may take place in a set of compositionally different layers, which may inhibit the upward heat transport.[22][23]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Sromovsky & Fry 2005.

- ISBN 9781139495066. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Smith Soderblom et al. 1986.

- ^ a b c d Lakdawalla 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hammel Sromovsky et al. 2009.

- ^ Perrotin, Henri (1 May 1884). "The Aspect of Uranus". Nature. 30: 21. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Hammel de Pater et al. ("Uranus in 2003") 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Rages Hammel et al. 2004.

- ^ a b Sromovsky Fry et al. 2009.

- ^ a b c Karkoschka ("Uranus") 2001.

- ^ a b c d Hammel de Pater et al. ("Uranus in 2004") 2005.

- ^ a b Sromovsky Fry et al. 2006.

- ^ a b Hanel Conrath et al. 1986.

- ^ Hammel Rages et al. 2001.

- ^ Shepherd, George (1861). The Climate of England. Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. p. 28. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

The planet Uranus completes her revolution round the sun in 84 years.

- ^ a b c d Lockwood & Jerzykiewicz 2006.

- ^ a b Klein & Hofstadter 2006.

- ^ a b c Young 2001.

- ^ a b c Hofstadter & Butler 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f Hammel & Lockwood 2007.

- ^ Devitt 2004.

- ^ a b c d Pearl Conrath et al. 1990.

- ^ a b c Lunine 1993.

- ^ Podolak Weizman et al. 1995.

Sources

- Devitt, Terry (10 November 2004). "Keck zooms in on the weird weather of Uranus". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- Hammel, H. B.; De Pater, I.; Gibbard, S. G.; Lockwood, G. W.; Rages, K. (June 2005). "Uranus in 2003: Zonal winds, banded structure, and discrete features" (PDF). Icarus. 175 (2): 534–545. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.11.012. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- Hammel, H. B.; Depater, I.; Gibbard, S. G.; Lockwood, G. W.; Rages, K. (May 2005). "New cloud activity on Uranus in 2004: First detection of a southern feature at 2.2 μm" (PDF). Icarus. 175 (1): 284–288. OSTI 15016781. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- Hammel, H. B.; Lockwood, G. W. (January 2007). "Long-term atmospheric variability on Uranus and Neptune". Icarus. 186 (1): 291–301. .

- Hammel, H. B.; Rages, K.; Lockwood, G. W.; Karkoschka, E.; de Pater, I. (October 2001). "New Measurements of the Winds of Uranus". Icarus. 153 (2): 229–235. .

- Hammel, H. B.; Sromovsky, L. A.; Fry, P. M.; Rages, K.; Showalter, M.; de Pater, I.; van Dam, M. A.; LeBeau, R. P.; Deng, X. (May 2009). "The Dark Spot in the atmosphere of Uranus in 2006: Discovery, description, and dynamical simulations" (PDF). Icarus. 201 (1): 257–271. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.08.019. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-19.

- Hanel, R.; Conrath, B.; Flasar, F. M.; Kunde, V.; Maguire, W.; Pearl, J.; Pirraglia, J.; Samuelson, R.; Cruikshank, D. (4 July 1986). "Infrared Observations of the Uranian System". Science. 233 (4759): 70–74. S2CID 29994902.

- Hofstadter, M. D.; Butler, B. J. (September 2003). "Seasonal change in the deep atmosphere of Uranus". Icarus. 165 (1): 168–180. .

- Karkoschka, Erich (May 2001). "Uranus' Apparent Seasonal Variability in 25 HST Filters". Icarus. 151 (1): 84–92. .

- Klein, M. J.; Hofstadter, M. D. (September 2006). "Long-term variations in the microwave brightness temperature of the Uranus atmosphere" (PDF). Icarus. 184 (1): 170–180. .

- Lakdawalla, Emily (11 November 2004). "No Longer Boring: 'Fireworks' and Other Surprises at Uranus Spotted Through Adaptive Optics". Planetary News: Observing from Earth. The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- Lockwood, G. W.; Jerzykiewicz, M. A. A. (February 2006). "Photometric variability of Uranus and Neptune, 1950–2004". Icarus. 180 (2): 442–452. .

- Lunine, Jonathan I. (September 1993). "The Atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 31: 217–263. .

- Pearl, J. C.; Conrath, B. J.; Hanel, R. A.; Pirraglia, J. A.; Coustenis, A. (March 1990). "The albedo, effective temperature, and energy balance of Uranus, as determined from Voyager IRIS data". Icarus. 84 (1): 12–28. ISSN 0019-1035.

- Podolak, M.; Weizman, A.; Marley, M. (December 1995). "Comparative models of Uranus and Neptune". Planetary and Space Science. 43 (12): 1517–1522. .

- Rages, K. A.; Hammel, H. B.; Friedson, A. J. (11 September 2004). "Evidence for temporal change at Uranus' south pole". Icarus. 172 (2): 548–554. .

- Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Beebe, A.; Bliss, D.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A.; Briggs, G. A.; Brown, R. H.; Collins, S. A. (4 July 1986). "Voyager 2 in the Uranian System: Imaging Science Results". Science. 233 (4759): 43–64. S2CID 5895824.

- Sromovsky, L. A.; Fry, P. M. (December 2005). "Dynamics of cloud features on Uranus". Icarus. 179 (2): 459–484. .

- Sromovsky, L. A.; Fry, P. M.; Hammel, H. B.; Ahue, W. M.; de Pater, I.; Rages, K. A.; Showalter, M. R.; van Dam, M. A. (September 2009). "Uranus at equinox: Cloud morphology and dynamics". Icarus. 203 (1): 265–286. S2CID 119107838.

- Sromovsky, L.; Fry, P.; Hammel, H.; Rages, K. (September 28, 2006). "Hubble Discovers a Dark Cloud in the Atmosphere of Uranus" (PDF). PHYSorg.com. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

- Young, L. (2001). "Uranus after Solstice: Results from the 1998 November 6 Occultation" (PDF). Icarus. 153 (2): 236–247. .

External links

- What is the Temperature of Uranus? by Nola Taylor

- Uranus Facts