Georg Eberhard Rumphius

Georg Eberhard Rumphius (originally: Rumpf; baptized c. 1 November 1627 – 15 June 1702) was a

Early life

Rumphius was the oldest son of August Rumpf, a builder and engineer in Hanau, and Anna Elisabeth Keller, sister of Johann Eberhard Keller, governor of the Dutch-speaking Kleve (Cleves), at that time a district of the Electorate (Kurfürstentum) of Brandenburg. Around 1 November 1627, he was baptized Georg Eberhard Rumpf in Wölfersheim, likely indicating he was born in October 1627. He grew up in Wölfersheim and attended the Gymnasium in Hanau.

Although born and raised in Germany, he spoke and wrote in Dutch from an early age, probably as learned from his mother. He was recruited by the West India Company, ostensibly to serve the Republic of Venice, but was put on a ship "De Swarte Raef" (The Black Raven) in 1646 bound for Brazil where the Dutch and Portuguese were fighting over territory. Either through shipwreck or capture he landed in Portugal, where he remained for nearly three years. Around 1649 he returned to Hanau where he helped his father's business.[1]

Merchant of Ambon

A week after his mother's funeral (20 December 1651) he left Hanau for the last time. Perhaps through contacts of his mother's family, he enlisted with the

Herbarium Amboinense

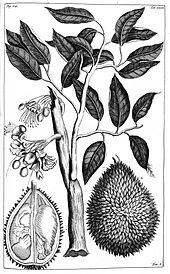

Rumphius is best known for his authorship of Het Amboinsche kruidboek or Herbarium Amboinense, a

After going blind in 1670 due to

The original manuscript of Het Amboinsch Kruidboek (MS BPL 314) is held at

The Herbarium Amboinense as published in 1741 consisted of six large folio volumes. Being blind, Rumphius required the assistance of others to produce it. His wife, Suzanna, was one of the early assistants and she was commemorated in Flos Susannae a white orchid (now Pecteilis susannae) described by Rumphius. His son Paul August made many of the plant illustrations as also the only known portrait of Rumphius. Other assistants included Philips van Eyck, a draughtsman, Daniel Crul, Pieter de Ruyter a soldier trained by Van Eyck, Johan Philip Sipman, Christiaen Gieraerts J. Hoogeboom[1] An English translation by E. M. Beekman, which took seven years to make, was posthumously published in 2011.[9]

Among the many species described in the Herbarium was the upas tree (

The other major work D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer ("Amboinese Cabinet of Curiosities"), a manuscript he had sent to Dr Hendrik D'Acquet of Delft in 1701 consisted mainly of plates of seashells and crabs.[6]

After Rumphius' death, his son Paul August was appointed "merchant of Amboina", the position his father had held. A monument was erected to the memory of Rumphius at Amboina but this was destroyed by the English who believed they would find gold under it. In 1824 a second monument was built by Governor-General van der Capellen but this was destroyed by a bomb in World War II.[1]

Works

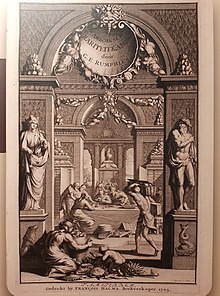

- Schijnvoet, Simon, ed. (1705). D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer: Behelzende eene beschryvinge van allerhande zoo weeke als harde Schaalvisschen, te weeten raare Krabben, Kreeften, en diergelyke Zeedieren, als mede allerhande Hoorntjes en Schulpen, die men in d'Amboinsche Zee vindt (in Dutch). T'Amsterdam: gedrukt by François Halma boekverkoper.

- Beekman, Eric Montague, ed. (1999). The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet (in Dutch and English). Translated, edited, annotated, and with an introduction. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07534-0.

- Beekman, Eric Montague, ed. (1999). The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet (in Dutch and English). Translated, edited, annotated, and with an introduction. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1741). Het Amboinsche kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 1. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1741). Het Amboinsche kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 2. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1743). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 3. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1743). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 4. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Jan Catuffe, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1747). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 5. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Burmannus, Joannes, ed. (1750). Het Amboinsch kruid-boek: Dat is, beschryving van de meest bekende boomen, heesters, kruiden, land-en water-planten, die men in Amboina, en de omleggende eylanden vind—Herbarium Amboinense, plurimas conplectens arbores, frutices, herbas, plantas terrestres & aquaticas, quae in Amboina, et adjacentibus reperiuntur insulis (in Dutch and Latin). Vol. 6. Te Amsterdam: by François Changuion, Hermanus Uytwerf.

- Amboinsch Kruid-boek. Auctuarium (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Meyndert Uytwerf (2.). 1755.

- Amboinsche Historie (Amboina History)

- Amboinsche Lant-beschrijvinge (a social geography)

- Amboinsch Dierboek (Amboina animal book, lost)

References

- ^ JSTOR 1217885.

- ^ a b c Meeuse, B.J.D. (1965). "Straddling two worlds: A biographical sketch of Georg Everhard Rumphius, Plinius Indicus". The Biologist. 68 (3–4): 42–54.

- Merrill, Elmer D. (1 Nov 1917). An Interpretation of Rumphius's Herbarium Amboinense. Vol. Publication No. 9. Manila, Philippines: Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Bureau of Science. pp. 1–595.

- ^ ISBN 962-593-076-0.

- ^ "museumboerhaave.nl". Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ S2CID 144849243.

- ^ Baas, Pieter and Jan Frits Veldkamp (2013). "Dutch pre-colonial botany and Rumphius's Ambonese Herbal" (PDF). Allertonia. 13: 9–19.

- Leiden University Libraries. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ .

- ^ Bastin, John (1985). "New light on J.N. Foersch and the celebrated poison tree of Java". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 58 (2): 25–44.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Rumph.

Sources

- Wehner, U., W. Zierau, & J. Arditti The merchant of Ambon: Plinius Indicus, in Orchid Biology: Reviews and Perspectives, pp 8–35. Tiiu Kull, Joseph Arditti, editors, Springer Verlag 2002

- Georg Eberhard Rumpf and E.M. Beekman (1999). The Ambonese curiosity cabinet - Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, Yale University Press (New Haven, Connecticut): cxii + 567 p. (ISBN 0300075340) English translation preceded by an account of his life and work and with annotations.

External links

Media related to Georg Eberhard Rumpf at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Georg Eberhard Rumpf at Wikimedia Commons- An interpretation of Rumphius's Herbarium amboinense (1917) by E.D. Merrill

- Rumphius Gedenkboek (1902) [="Rumphius memorial book" in Dutch]

- Rumpf, George Eberhard (1741) D'Amboinsche rariteitkamer - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library