Harry Morley

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Harry Morley | |

|---|---|

Morley's etched Self Portrait 1923 & 28 | |

| Born | Harry Morley 5 April 1881 Leicester, England |

| Died | 18 September 1943 (aged 62) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Painting, etching and engraving |

Harry Morley

Early life

Morley was born in

Marriage and family

In London 1911, Harry Morley married Lilias Helen Swain ARCA (1880-1973). A skilful calligrapher and embroiderer, Swain had studied design at the Royal College of Art under William Lethaby. She was trained in lettering and illumination by Professor Edward Johnston and went on to become his first assistant. She studied embroidery under Grace Christie (1872-1953) whom she assisted after her graduation. Swain was teaching calligraphy and embroidery at the Royal College when she became engaged to Morley.[2][7]

With fees from a commission to illustrate A Wanderer in Florence by E. V. Lucas (1912), Harry and Lilias Morley honeymooned in Florence.[citation needed] The couple travelled on to Venice and Paris, studied paintings in the galleries and sketched. Watercolours made by Morley in Venice were used two years later to illustrate Lucas's A Wanderer in Venice (1914). His watercolours of Paris were published in The Charm of Paris by Alfred H. Hyatt in 1913. In 1926, he was commissioned to illustrate a third book by Lucas, A Wanderer in Rome. The bird's-eye maps of Italian cities that appear on the end papers of all three books for Lucas were drawn by Morley and feature his wife's calligraphy.[citation needed]

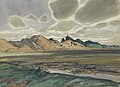

The couple lived in London where they had two daughters, Elinor Beryl (7 September 1912 - 26 September 1998) and Julia Morley (2 September 1917 - 16 May 2008). During August each year, Morley and his family took regular sketching holidays to countryside or coastal areas of England and Wales.[citation needed] His watercolours, which looked back to the English landscape tradition with a 'strong sense of place, technical assurance and characteristic integrity' were noted for their 'freedom and spontaneity'. In contrast, his oil and tempera paintings were 'painstakingly constructed', reflecting Morley's admiration for the early Italian painting tradition.[7]

Lilias all but gave up her artistic career to support Morley in his work. Whenever the opportunity arose, she undertook private commissions in calligraphy and embroidery design. She continued to draw and paint under the name Lester Romley. A quiet feminist from an early age, Lilias shared digs in Chelsea with fellow Royal College of Art student Sylvia Pankhurst, who like Lilias was from Manchester. Lilias designed and embroidered for the Pankhursts a demonstration banner (now lost).[8]

1920s

By 1921 Morley had been elected a member of the Art Workers' Guild. He joined the Society of Painters in Tempera two years later. The ethos and camaraderie of artist groups appealed to him. He was an active member of both organisations. The Society of Painters in Tempera frequently held their meetings in Morley's studio. John D. Batten, the painter-activist Mary Sargant Florence, Francis Ernest Jackson, Maxwell Armfield and Joseph Southall were among the many that attended. The revival of British interest in tempera painting had begun as early as 1901 with the formation of the Society. By the 1920s the medium was better understood. However, it was only after the Royal Academy of Arts' groundbreaking Italian Art exhibition at Burlington House in 1930 that the academy accepted contemporary tempera paintings in its Summer Exhibition. A tempera of Morley's was one of the thirty-six tempera paintings shown that first year.[9]

Morley was considered to be an 'artist's artist'. His pictures 'proclaim their dependence on the early Italian masters, not only by their oil and tempera technique but in their visual vocabulary'. The artist's 'strong sense of monumental form and spatial clarity' reflected his early training as an architect. Together with his use of clean lines, academic coolness and detachment, Morley's work is clearly distinguished from the narrative purpose and sentiment of the Pre-Raphaelites.[10]

Morley's principal concern was the mythological and biblical figure paintings in oil and tempera that he exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts from 1912. In 1924 his tempera painting, Apollo and Marsyas was purchased for the

Printmaking

In 1925, commissions to illustrate E. V. Lucas' A Wanderer in Rome (1926) and Edward Hutton's Cities of Sicily (1926) allowed Morley and his wife to return to Italy. For several years they spent a few months each Spring travelling and working in Italy. In 1928 they stayed with the artist Job Nixon sharing his studio in Anticoli Corrado. The following year, Robert Austin joined the Morleys in Anticoli. In search of interesting subjects the two men accompanied villagers of Ancticoli Corrado on an annual pilgrimage to the Sanctuary of the Madonna della Figura, Sora in the Lazio hills.[citation needed]

While Morley's etchings are vigorous and experimental, his line engravings are precise and considered. Arguably, the engravings reveal the Arts and Crafts influence of his student days. They certainly reflect his knowledge and appreciation of Italian Quattrocento art. In 1930 Morley, Robert Austin and his brother Frederick Austin staged an exhibition at Leicester City Art Gallery.[2]

1930s

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

Despite the collapse of the art market during the economic depression that followed the 1929

Morley was appointed to the Faculty of Engraving at the British School at Rome in 1931. He was elected Associate of the Royal Watercolour Society (RWS) in 1927 and a full member in 1931. He served as RWS Vice President from 1937 to 1941. Having been nominated for Associate Membership of the Royal Academy of Arts (ARA) since 1921, he was eventually elected ARA in 1936.[2] That same year he was also elected Master of the Art Workers' Guild.[11] He was also chair of the Association of Student Sketch Clubs.[12] A series of six articles by Morley on the 'Theory and Practice of Figure Painting in Oils' appeared in The Artist magazine between September 1936 to February 1937.[citation needed]

Morley's mythological and classical figure compositions helped establish his reputation and attract critical approval. By the mid-1930s, however, he had begun to experiment with a new approach to landscape painting, influenced in part by his longstanding admiration for the work of Paul Cézanne. Were it not for the disruption caused by World War II, his relocation out of London, his ill-health and early death, it is impossible to tell where this new direction might have led.[citation needed]

World War II

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

A weak heart and lifelong asthma excluded Morley from active duty during both wars. In 1940 Morley was staying at the Bishop's Palace, Wells working on his portrait The Very Reverend Bishop Underwood of Bath and Wells when his London home and studio were damaged by a bomb.[citation needed] Though Lilias and Julia Morley were unharmed, pieces of the bomb were found in the back garden and the house and studio were uninhabitable. Morley and his family relocated to live with his newly married daughter Beryl and her husband Captain John Castle. They shared a small cottage in Wool, Dorset near Bovington Camp where Castle trained soldiers to drive tanks.[citation needed]

The Ministry of Information provided Morley with a permit to produce drawings of the Camp. Other commissions followed including one to record the destruction at Southampton docks. Morley also completed a number of short commissions for the War Artists' Advisory Committee. These paintings are now housed in the Imperial War Museum.[13] During his time at Wool, Morley suffered his first heart attack.[citation needed]

During his last years Morley undertook several posthumous portrait commissions of men who had lost their lives in the war. Though glad of the income, he regretted the sad circumstances under which he was working. The last of these portraits,

Memberships

Morley was a member of or affiliated with the following organisations:[4]

- 1927: Associate member of the Royal Watercolour Society,

- 1929: Associate member of Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers,

- 1931: Member of Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers,

- 1931: Member of the Royal Watercolour Society,

- 1935: Member of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters

- 1936: Associate of the Royal Academy,

- 1937-41: Vice President of the Royal Watercolour Society.[3] (VPRWS)

References

- ^ "Harry Morley". Hargrave Fine Art. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ ISBN 0-85022-102-1.

- ^ ISBN 1-85149-106-6.

- ^ a b c Grant M. Waters (1975). Dictionary of British Artists Working 1900-1950. Eastbourne Fine Art.

- ISBN 2-7000-3079-6.

- ^ "Artist biography, Harry Morley". British Council. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ ISBN 0-85331-552-3.

- ISSN 1742-254X.

- ISBN 9780905062174.

- OCLC 863253825.

- ^ The Year's Art. 1937. p. 106.

- ^ The Year's Art. 1937. p. 114.

- ^ "War artists archive". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

External links

- 26 artworks by or after Harry Morley at the Art UK site