Hop-Frog

| "Hop-Frog" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Edgar Allan Poe | |

| |

| Original title | Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror Short story |

| Publication | |

| Published in | The Flag of Our Union |

| Publisher | Frederick Gleason |

| Media type | |

| Publication date | March 17, 1849 |

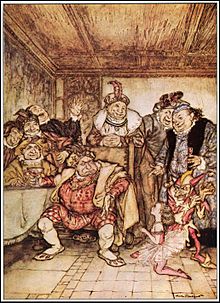

"Hop-Frog" (originally "Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs") is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1849. The title character, a person with dwarfism taken from his homeland, becomes the jester of a king particularly fond of practical jokes. Taking revenge on the king and his cabinet for the king's striking of his friend and fellow dwarf Trippetta, he dresses the king and his cabinet as orangutans for a masquerade. In front of the king's guests, Hop-Frog murders them all by setting their costumes on fire before escaping with Trippetta.

Critical analysis has suggested that Poe wrote the story as a form of literary revenge against a woman named Elizabeth F. Ellet and her circle.

Plot summary

The court jester Hop-Frog, "being also a dwarf and a cripple", is the much-abused "fool" of the unnamed king. This king has an insatiable sense of humor: "he seemed to live only for joking". Both Hop-Frog and his best friend, the dancer Trippetta (also small, but beautiful and well-proportioned), have been stolen from their homeland and essentially function as slaves. Because of his physical deformity, which prevents him from walking upright, the King nicknames him "Hop-Frog".

Hop-Frog reacts severely to

As predicted, the guests are shocked and many believe the men to be real "beasts of some kind in reality, if not precisely ourang-outangs". Many rush for the doors to escape, but the King had insisted the doors be locked; the keys are left with Hop-Frog. Amidst the chaos, Hop-Frog attaches a chain from the ceiling to the chain linked around the men in costume. The chain then pulls them up via pulley (presumably by Trippetta, who has arranged the room to help with the scheme) far above the crowd. Hop-Frog puts on a spectacle so that the guests presume "the whole matter as a well-contrived pleasantry". He claims he can identify the culprits by looking at them up close. He climbs up to their level, grits his teeth again, and holds a torch close to the men's faces. They quickly catch fire: "In less than half a minute the whole eight ourang-outangs were blazing fiercely, amid the shrieks of the multitude who gazed at them from below, horror-stricken, and without the power to render them the slightest assistance". Finally, before escaping through a sky-light, Hop-Frog identifies the men in costume:

I now see distinctly... what manner of people these maskers are. They are a great king and his seven privy-councillors—a king who does not scruple to strike a defenceless girl, and his seven councillors who abet him in the outrage. As for myself, I am simply Hop-Frog, the jester—and this is my last jest.

The ending explains that, after that night, neither Hop-Frog nor Tripetta were ever seen again. It is implied that she was his accomplice and that they fled together back to their home country.

Analysis

The story, like "The Cask of Amontillado", is one of Poe's revenge tales, in which a murderer apparently escapes without punishment. In "The Cask of Amontillado", the victim wears motley; in "Hop-Frog", the murderer also dons such attire. However, while "The Cask of Amontillado" is told from the murderer's point of view, "Hop-Frog" is told from an unidentified third-person narrator's point of view.

The grating of Hop-Frog's teeth, right after Hop-Frog witnesses the king splash wine in Trippetta's face, and again just before Hop-Frog sets the eight men on fire, may well be symbolic. Poe often used teeth as a sign of mortality, as with the lips writhing about the teeth of the mesmerized man in "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" or the obsession with teeth in "Berenice".[1]

"The Cask of Amontillado" represents Poe's attempt at literary revenge on a personal enemy,[2] and "Hop-Frog" may have had a similar motivation. As Poe had been pursuing relationships with Sarah Helen Whitman and Nancy Richmond (whether romantic or platonic is uncertain), members of literary circles in New York City spread gossip and incited scandal about alleged improprieties. At the center of this gossip was a woman named Elizabeth F. Ellet, whose affections Poe had previously scorned. Ellet may be represented by the king himself, with his seven councilors representing Margaret Fuller, Hiram Fuller (no relation), Thomas Dunn English, Anne Lynch Botta, Anna Blackwell, Ermina Jane Locke, and Locke's husband.[3]

The tale is arguably autobiographical in other ways. The jester Hop-Frog, like Poe, is "kidnapped from home and presented to the king" (his wealthy foster father John Allan), "bearing a name not given in baptism but 'conferred upon him'" and is susceptible to wine ... when insulted and forced to drink becomes insane with rage".[4] Like Hop-Frog, Poe was bothered by those who urged him to drink, despite a single glass of wine making him drunk.[5]

Poe could have based the story on the

Publication history

The tale first appeared in the March 17, 1849 edition of The Flag of Our Union, a Boston-based newspaper published by Frederick Gleason and edited by Maturin Murray Ballou. It originally carried the full title "Hop Frog; Or, The Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs". In a letter to friend Nancy Richmond, Poe wrote: "The 5 prose pages I finished yesterday are called — what do you think? — I am sure you will never guess — Hop-Frog! Only think of your Eddy writing a story with such a name as 'Hop-Frog'!"[8]

He explained that, though The Flag of Our Union was not a respectable journal "in a literary point of view", it paid very well.[8]

Adaptations

- French director Henri Desfontaines made the earliest film adaptation of "Hop-Frog" in 1910.

- James Ensor's 1896 painting titled, Hop-Frog's Revenge, is based on the story.

- A 1926 symphony by Eugene Cools was inspired by and named after Hop-Frog.

- A plot similar to "Hop-Frog" is used as a side plot in Roger Corman's The Masque of the Red Death (1964), starring Vincent Price as "Prince Prospero". Enraged by Prospero's friend Alfredo hitting his partner for accidentally knocking his cup of wine during her dance number, the dwarf artist sets him on fire during the masquerade after dressing him up in a gorilla costume. Hop-Frog (called Hop-Toad in the film) is played by the actor Skip Martin, who was a "little person", but his dancing partner Esmeralda (analogous to Trippetta from the short story) is played by a child overdubbed with an older woman's voice.

- Elements of the tale are suggested in climax of the 1962 Hammer adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera (directed by Terence Fisher), the idea of a dwarf utilizing a chandelier as a murder weapon being particularly noteworthy.

- Illustrated versions of the story appeared in the horror comic magazines Nightmare[9] and Creepy.[10]

- In 1992, Julie Taymor directed a short film entitled Fool's Fire adapted from "Hop-Frog". Michael J. Anderson of Twin Peaks fame starred as "Hop-Frog" and Mireille Mosse as "Trippetta", with Tom Hewitt as "The King". The film aired on PBS's American Playhouse and depicts all "normal" characters being dressed in masks and costumes (designed by Taymor) with only Hop-Frog and Trippetta shown as they truly are. Poe's poems "The Bells" and "A Dream Within a Dream" are also used as part of the story.

- A radio-drama production of "Hop-Frog" was broadcast in 1998 in the National Public Radio. The story was performed by Winifred Phillipsand included music composed by her.

- The story features as part of Lou Reed's 2003 double album The Raven. One of the tracks is a song called "Hop-Frog" sung by David Bowie.

- Lance Tait's 2003 play Hop-Frog is based on this story. Laura Grace Pattillo wrote in The Edgar Allan Poe Review (2006), "a visually striking piece of theatrical storytelling, is Tait's adaptation of 'Hop-Frog'. In this play, the device of the Chorus functions exceptionally well, as one male and one female actor help narrate the story and speak for all of the supporting characters, who are represented by objects such as a long piece of wood and a collection of candles."[11]

- In 2020, the British experimental rock band Black Midi adapted "Hop-Frog" as a spoken-word piece with instrumental accompaniment on their album The Black Midi Anthology Vol. 1: Tales of Suspense and Revenge. The story is narrated by lead singer Geordie Greep.[12]

References

- ISBN 0-300-03773-2.

- ^ Rust, Richard D. (Fall 2001). "Punish with Impunity: Poe, Thomas Dunn English and 'The Cask of Amontillado'". The Edgar Allan Poe Review. 2 (2). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: St. Joseph's University.

- ISBN 978-0961644918.

- ISBN 978-0060923310.

- ^ ISBN 0-8018-5730-9.

- ^ Tuchman (1979), 503–505

- ISBN 978-0809324712.

- ^ ISBN 0-8018-5730-9.

- ^ Angelo Torres (art): "Hop-Frog". Nightmare #11 (February 1954).

- ^ Reed Crandall (artist) and Archie Goodwin (story): "Hop-Frog". Creepy #11 (July 14, 1966), pp. 5-12.

- JSTOR 41506252.

- ^ "Black Midi share jam spoken word album 'The Black Midi Anthology Vol. 1: Tales of Suspense and Revenge'". NME. 6 June 2020.

External links

Works related to Hop-Frog at Wikisource

Works related to Hop-Frog at Wikisource Media related to Hop-Frog at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hop-Frog at Wikimedia Commons Hop-Frog public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Hop-Frog public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "Hop-Frog", The Flag of Our Union, March 17, 1849, page 2. Library of Congress.