Ida B. Wells Homes

| Ida B. Wells Homes | |

|---|---|

| Status | Demolished |

| Construction | |

| Constructed | 1939–41; Ida B. Wells Homes 1961; Darrow Homes 1970; Madden Park Homes |

| Demolished | 2002–11 |

| Other information | |

| Governing body | Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) |

The Ida B. Wells Homes, which also comprised the Clarence Darrow Homes and Madden Park Homes, was a

History

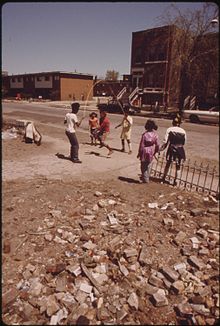

Named for African American journalist and newspaper editor Ida B. Wells,[1] the housing project was constructed between 1939 and 1941 as a Public Works Administration project to house black families in the "ghetto", in accordance with federal regulations requiring public housing projects to maintain the segregation of neighborhoods.[2][3][4] It was the fourth public housing project constructed in Chicago before World War II and was much larger than the others, with 1,662 units.[2] It had more than 860 apartments and almost 800 row houses and garden apartments,[1] and included a city park, Madden Park. Described as "handsome [and] well planned", the project was initially a sought-after address and a route to success.[5][6]

Darrow Homes and Madden Park Homes

In 1961, the Clarence Darrow Homes were built adjacent to the Ida B. Wells Homes and in 1970, the last of the Chicago Housing Authority's high-rise projects, the Madden Park Homes, were built east of the Wells.[7] The "three huge, contiguous projects" lined the northern edge of the Oakland community area.[8]

Problems

Demolition

In 1995, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development took over the Chicago Housing Authority's public housing projects and decided to demolish the high-rises. Demolition began at the Ida B. Wells Homes in late 2002 with the high-rise buildings on Cottage Grove Avenue. It was completed in August 2011 with the demolition of the last two residential buildings at 3718 S. Vincennes Avenue.[20] Construction began in 2003 on the mixed-income community of Oakwood Shores, which will replace all three housing projects, Ida B. Wells, Madden Park, and Clarence Darrow,[21][22] A commission, led by Well's great grand-daughters raised funds for a public memorial to honor Wells near the site, which had also been close to Wells' own neighborhood.[1][23][24] The Light of Truth Ida B. Wells National Monument created by well known abstract sculptor and Chicago artist Richard Hunt was unveiled on June 29, 2021.[25]

See also

- Cabrini Green

References

- ^ Huffington Post, December 28, 2011.

- ^ Chicago Historical Society, 2005.

- ISBN 9781594513817, p. 121.

- ISBN 9780226774985, p. 14.

- .

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, "The Origins of the Underclass," Part One, The Atlantic, July 1986: "It is common in Chicago to meet successful blacks in their late thirties and early forties who spent part of their childhood in the projects."

- ^ Madden Wells Homes, Frank's Masonry.

- ISBN 9780810123441, p. 295.

- ^ Tom McNamee, "Ida B. Wells - big and bad", Chicago Sun-Times, December 7, 1986.

- ISBN 9780226366043, p. 89.

- ^ Jerry Thornton and Robert Blau, "Police Say Shooting May Have Been Ordered By Rukns", Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1988.

- ^ Charles Nicodemus, "`Major, Major' Drug Ring Broken", Chicago Sun-Times, May 20, 1995.

- ^ Don Terry, "Graduation Ends a Partnership Born in a Chicago Ghetto", The New York Times, June 9, 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Remorse: The 14 Stories of Eric Morse Archived 2010-06-25 at the Wayback Machine, Sound Portraits.

- ^ 1 Remorse": Two children of the Chicago projects have made a remarkable documentary on the life and death of 5-year-old Eric Morse, killed for refusing to steal candy. Their work will be broadcast tomorrow on NPR. VOICES OF EXPERIENCE March 20, 1996

- ^ Flynn McRoberts, Julie Irwin, et al., "A Search for Answers in Eric's Fatal Fall", Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1994.

- ^ Roger Ebert, "'Housing' unlocks truth: Filmmaker lets camera tell CHA residents' story", Chicago Sun-Times, November 27, 1997.

- ^ John McCarron, "Cinema Verite: Wiseman's Unflinching Look at Life in the CHA", Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1997: "'Public Housing' was filmed entirely within the Ida B. Wells public housing complex".

- ^ Elise Nakhnikian, "Fred Wiseman Is There: Public Housing", The Measure, The L Magazine, October 15, 2010.

- ^ Jacqueline Thompson, Ida B. Wells Revisited, Residents' Journal, We The People Media, October 5, 2011.

- ^ Oakwood Shores Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Housing Authority.

- ^ Oakland Archived 2012-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, South East Chicago Commission.

- ^ Ron Grossman, "Supporters propose monument to Ida B. Wells: Ex-residents of the vanished housing complex named for the civil rights pioneer call for a lasting tribute", Chicago Tribune, November 9, 2011.

- ^ Bronzeville, City to honor pioneer Ida B. Wells Archived 2013-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, Gazette Chicago, February 2, 2012.

- ^ Shaw, Nichole (2021-06-30). "Unveiling of Ida B. Wells Monument in Bronzeville met with 'joy, excitement, appreciation and humbleness'". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

Further reading

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- ISBN 9780684836164. Based on the two radio documentaries Ghetto Life 101and Remorse: The 14 Stories of Eric Morse.