Iron Age sword

Early Iron Age swords were significantly different from later steel swords. They were work-hardened, rather than quench-hardened, which made them about the same or only slightly better in terms of strength and hardness to earlier bronze swords. This meant that they could still be bent out of shape during use. The easier production, however, and the greater availability of the raw material allowed for much larger scale production.

Eventually

History

The

The iron version of the Scythian/Persian

Chinese steel swords make their appearance from the 5th century BC

jiàn) double edged.European swords

With the spread of the

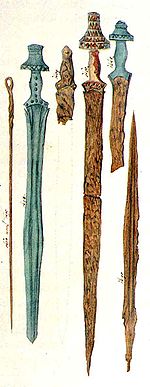

There are two kinds of Celtic sword. The most common is the "long" sword, which usually has a stylised anthropomorphic hilt made from

Scabbards were generally made from two plates of iron, and suspended from a belt made of iron links. Some scabbards had front plates of bronze rather than iron. This was more common on Insular examples than elsewhere; only a very few Continental examples are known.

Steppe cultures

Swords with ring-shaped pommels were popular among the Sarmatians from the 2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD. They were about 50 to 60 cm (20 to 24 in) in length, with a rarer "long" type in excess of 70 cm (28 in), in exceptional cases as long as 130 cm (51 in). A semi-precious stone was sometimes set in the pommel ring. These swords are found in great quantities in the Black Sea region and the Hungarian plain. They are similar to the akinakes used by the Persians and other Iranian peoples. The pommel ring probably evolves by closing the earlier arc-shaped pommel hilt which evolves out of the antenna type around the 4th century BC.[4]

Stability

There is other evidence of long-bladed swords bending during battle from later periods. The Icelandic Eyrbyggja saga,[7] describes a warrior straightening his twisted sword underfoot like Polybius's account: "Whenever he struck a shield, his ornamented sword would bend, and he had to put his foot on it to straighten it out".[8][9] Peirce and Oakeshott in Swords of the Viking Age note that the potential for bending may have been built in to avoid shattering, writing that "a bending failure offers a better chance of survival for the sword's wielder than the breaking of the blade...there was a need to build a fail-safe into the construction of a sword to favor bending over breaking".[10]

See also

- Pattern welding

- Bronze Age sword

- Early Iron Age

- Noric steel

- Spatha

- Migration Period sword

- Celtic warfare

- Asi (sword)

- Khanda (sword)

References

- ^ Maryon 1948.

- ^ Maryon 1960a.

- ^ Maryon 1960b.

- ISBN 978-1-84176-485-6, p. 34

- ^ a b Vagn Fabritius Buchwald, Iron and steel in ancient times, Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 2005, p.127.

- ^ a b c Radomir Pleiner, The Celtic Sword, Oxford: Clarendon Press (1993), p.159; 168.

- ^ R. Chartrand, Magnus Magnusson, Ian Heath, Mark Harrison, Keith Durham, The Vikings, Osprey, 2006, p.141.

- ^ Hermann Pálsson, Paul Geoffrey Edwards, Eyrbyggja saga, Penguin Classics, 1989, p.117.

- ^ The Saga of the Ere-Dwellers, Chapter 44 - The Battle In Swanfirth

- ^ Ian G. Peirce & Ewart Oakeshott, Swords of the Viking Age, Boydell Press, 2004, p.145.

Literature

- C. R. Cartwright, Janet Lang, British Iron Age Swords And Scabbards, British Museum Press (2006), ISBN 0-7141-2323-4.

- Andrew Lang, Celtic Sword Blades, in Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1907).

- doi:10.5284/1034398.

- JSTOR 1505063.

- JSTOR 1504953.

- J. M. de Navarro, The Finds from the Site of La Tène: Volume I: Scabbards and the Swords Found in Them, London: The British Academy, Oxford University Press (1972).

- Radomir Pleiner, The Celtic Sword, Oxford: Clarendon Press (1993).

- Graham Webster, A Late Celtic Sword-Belt with a Ring and Button Found at Coleford, Gloucestershire, Britannia, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies (1990).