Kataragama temple

| Kataragama temple | |

|---|---|

කතරගම கதிரகாமம் Ruhunu Maha Kataragama devalaya in Kataragama | |

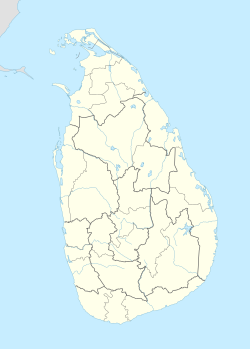

| Country | Sri Lanka |

| Geographic coordinates | 6°25′N 81°20′E / 6.417°N 81.333°E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | c. 1100 – 15th century[1][2] |

Kataragama temple (

The shrine has for centuries attracted Tamil Hindus from Sri Lanka and South India who undertook an arduous pilgrimage on foot. Since the latter half of the 20th century, the site has risen dramatically among Sinhalese Buddhists who today constitute majority of the visitors.[4]

The cult of Kataragama deviyo has become the most popular amongst the Sinhalese people. A number of legends and myths are associated with the deity and the location, differing by religion, ethnic affiliation and time. These legends are changing with the deity's burgeoning popularity with Buddhists, as the Buddhist ritual specialists and clergy try to accommodate the deity within Buddhist ideals of nontheism. With the change in devotees, the mode of worship and festivals has changed from that of Hindu orientation to one that accommodates Buddhist rituals and theology. It is difficult to reconstruct the factual history of the place and the reason for its popularity amongst Sri Lankans and Indians based on legends and available archeological and literary evidence alone, although the place seems to have a venerable history. The lack of clear historic records and resultant legends and myths fuel the conflict between Buddhists and Hindus as to the ownership and the mode of worship at Kataragama.[5]

The priests of the temple are known as Kapuralas and are believed to be descended from Vedda people. Veddas, too, have a claim on the temple, a nearby mountain peak and locality through a number of legends. There is a mosque and a few tombs of Muslim pious men buried nearby. The temple complex is also connected to other similar temples in

History

Origin theories

There are number of theories as to the origin of the shrine. According to

Literary evidence

The first literary mention of Kataragama in a context of a sacred place to kandha-Murugan is in its

Archeological evidence

The vicinity of the temple has number of ancient ruins and inscriptions. Based on dated inscriptions found, the nearby

Role of Kalyangiri Swamy

The medieval phase of the history of the shrine began with the arrival of Kalyanagiri Swamy from North India sometimes during the 16th or 17th century.[17] He identified the very spot of the shrines and their mythic associations with characters and events as expounded in Skanda Purana.[17] Following his re-establishment of the forest shrine, it again became a place of pilgrimage for Indian and Sri Lankan Hindus. The shrine also attracted local Sinhala Buddhist devotees.[17] The caretakers of the shrines were people of the forest who were of indigenous Vedda or mixed Vedda and Sinhalese lineages. The shrines popularity increased with the veneration of the place by the kings of the Kingdom of Kandy, the last indigenous kingdom before colonial occupation of the island. When Indian indentured workers were brought in after the British occupation in 1815, they too began to participate in the pilgrimage in droves,[18] thus the popularity of the shrine increased amongst all sections of the people.[19]

"The Katragam dewale consists of two apartments, of which the outer one only is accessible. Its walls are ornamented with figures of different gods, and with historical paintings executed in the usual style. Its ceiling is a mystically painted cloth, and the door of the inner apartment is hid by a similar cloth. On the left of the door there is a small foot-bath and basin, in which the officiating priest washes his feet and hands before he enters the sanctum. Though the idol was still in the jungle where it had been removed during the rebellion, the inner room appropriated to it was as jealously guarded as before"

Legends

Hindu legends

According to Hindus and some Buddhist texts, the main shrine is dedicated to Kartikeya, known as Murugan in Tamil sources. Kartikeya, also known as Kumara, Skanda, Saravanabhava, Visakha or Mahasena, is the chief of warriors of celestial Gods.[20] The Kushan Empires and the Yaudheyas had his likeness minted in coins that they issued in the last centuries BCE. The deity's popularity has waned in North India but has survived in South India. In South India, he became known as Subrahmaniya and was eventually fused with another local god of war known as Murugan among Tamils.[21] Murugan is known independently from Sangam literature dated from the 2nd century BCE to the 6th century CE.[22] Along the way, a number of legends were woven about the deity's birth, accomplishments, and marriages, including one to a tribal princess known amongst Tamil and Sinhalese sources as Valli. The Skanda Purana, written in Sanskrit in the 7th or 8th century, is the primary corpus of all literature about him.[23] A Tamil rendition of the Skanda Purana known as the Kandha Puranam written in the 14th century also expands on legends of Valli meeting Murugan. The Kandha Puranam plays a greater role for Sri Lankan Tamils than Tamils from India, who hardly know it.[24]

In Sri Lanka the Sinhala Buddhists also worshiped Kartikeya as Kumaradevio or Skanda-Kumara since at least the 4th century, if not earlier.[1] Skanda-Kumara was known as one of the guardian deities until the 14th century, invoked to protect the island; they are accommodated within the non-theistic Buddhist religion.[1] During the 11th and 12th century CE, the worship of Skanda-Kumara was documented even among the royal family.[1] At some point in the past Skanda-Kumara was identified with the deity in Kataragama shrine, also known as Kataragama deviyo and Kataragama deviyo, became one of the guardian deities of Sri Lanka.[1] Numerous legends have sprung about Kataragama deviyo, some of which try to find an independent origin for Katargamadevio from the Hindu roots of Skanda-Kumara.[25]

Buddhist legends

One of the Sinhala legends tells that when Skanda-Kumara moved to Sri Lanka, he asked for refuge from Tamils. The Tamils refused, and he came to live with the Sinhalese in Kataragama. As a penance for their refusal, the deity forced Tamils to indulge in body piercing and fire walking in his annual festival.

According to the practice of cursing and

Muslim legends

A number of Muslim pious and holy men seems to have migrated from India and settled down in the vicinity. The earliest known one is one Hayathu, whose simple residence became the mosque. Another one called Karima Nabi is supposed to have discovered a source of water that when drunk provides immortality.

Vedda legends

Temple layout

Almost all the shrines are nondescript small rectangular buildings without any ornamentation. There is no representative of deities adorning the outside of the buildings. This is in contrast to any other Hindu temple in Sri Lanka or India. Almost all shrines are built of stone except that one dedicated to Valli which shows timber construction. They have been left as originally constructed and there are not any plans to improve upon them, because people are reluctant to tamper with the original shrine complex.[38]

The most important one is known as Maha Devale or Maha Kovil and is dedicated to Skanda-Murugan known amongst the Sinhalese as Kataragama deviyo. It does not have a statute of the deity; instead it holds a

Attached to the western wall of the shrine complex are shrines dedicated

Murukan and Kataragama deviyo cults

Buddhism doesn't encourage veneration of deities, and yet Buddhists in Sri Lanka make an annual pilgrimage to Kataragama.[26] The deity has attained the position of national god amongst the Sinhalese. This reflects the similar position held by Murukan amongst Tamils.[40]

Murukan

Murukan is known from Sangam Tamil literature.

With advent of North Indian traditions arriving with the

Katargamadevio cult

Legends in Sri Lanka claimed that Valli was a daughter of a Vedda chief from Kataragama in the south of the island. The town of

Since the 1950s the cult of Kataragama has taken a nationalistic tone amongst the Sinhalese people. People visit the shrine year long, and during the annual festival it looks like a carnival.

Festivals

The festivals and daily rituals do not adhere to standard Hindu

Hindu and Buddhist conflicts

Sri Lanka has had a history of conflict between its minority Hindu Tamils and majority Buddhists since its political independence from Great Britain in 1948. Paul Wirz in the 1930s wrote about tensions between Hindus and Buddhists regarding the ownership and mode of ritual practice in Kataragama.[51] For the past millennia the majority of the pilgrims were Hindus from Sri Lanka and South India who undertook an arduous pilgrimage on foot.[52] By the 1940 roads were constructed and more and more Sinhala Buddhists began to take the pilgrimage.[35][53] This increased the tensions between the local Hindus and Buddhists about the ownership and type of rituals to be used.[51][54] The government interceded on behalf of the Buddhists and enabled the complete takeover of the temple complex and in effect the shrines have become an adjunct to the Buddhist Kiri Vehera.[31][55] Protests occurred upon this development in the 1940s, particularly when restrictions were placed on Tamil worship at the shrine.[56][57]

Typical Tamil Hindu rituals at Kataragama such as

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pathmanathan, S (September 1999). "The guardian deities of Sri Lanka:Skanda-Murgan and Kataragama". The Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies. The institute of Asian studies.

- ^ Peiris, Kamalika (31 July 2009). "Ancient and medieval Hindu temples in Sri Lanka". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Younger 2001, p. 39

- ISBN 9780195173987.

- ^ Wirz 1966, p. 16

- ^ See map.

- ^ Bechert 1970, pp. 199–200

- ^ a b Younger 2001, p. 26

- ^ Ancient Ceylon. Department of Archaeology, Sri Lanka. 1971. p. 158.

- ^ Wright, Michael (15 May 2007). "The facts behind the Jatukam Ramathep talisman nonsense". The Nation. The Buddhist Channel. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Reynolds 2006, p. 146

- ^ a b c Younger 2001, p. 27

- ^ Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam The Worship of Muruka or Skanda (The Kataragama God) First published in the Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XXIX, No. 77, 1924.

- ^ a b Wirz 1966, p. 17

- ^ Paranavitana 1933, pp. 221–225

- ^ Mahathevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Wirz 1966, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b c Younger 2001, p. 35

- ^ a b c Younger 2001, p. 33

- ^ Bhagavad Gita|Chapter 10|verse 20

- ^ Womak 2005, p. 126

- ^ Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, pp. 23–35

- ^ Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, p. 224

- ^ Gupta 2010, p. 167

- ^ Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1999, p. xii

- ^ a b Wanasundera 2004, p. 94

- ^ Wirz 1966, p. 19

- ^ Witane, Godwin (2001). "Kataragama: Its origin, era of decline and revival". The Island. The Island Group. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Raj 2006, p. 127

- ^ Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1999, pp. 163–200

- ^ a b c d e Feddema 1997, pp. 202–222

- ^ Kapferer 1997, p. 51

- ^ Younger 2001, p. 34

- ^ Wirz 1966, pp. 23–25

- ^ a b c Davidson & Gitlitz 2002, p. 309

- ^ a b Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, p. 38

- ^ Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, p. 39

- ^ a b c Wirz 1966, pp. 26–35

- ^ Wirz 1966, pp. 13–15

- ^ Holt 1991, p. 6

- ^ Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, p. 15

- ^ Klostermaier 2007, p. 251

- ^ Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, pp. 22

- ^ Clothey & Ramanujan 1978, pp. 128–130

- ^ Wirz 1966, pp. 36–45

- ^ Bastin 2002, p. 60

- ^ Gaveshaka (15 August 2004). "The exquisite wood carvings at Embekke". Sunday Times. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ Bastin 2002, p. 62

- ^ Younger 2001, pp. 27–31

- ^ Raj 2006, p. 117

- ^ a b Kandasamy, R (December 1986). "Sri Lanka's Most Holy Hindu Site becoming a Purely Buddhist Place of Worship?". Hinduism Today. Himalayan Academy. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Raj 2006, p. 111

- ^ Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1999, p. 189

- ^ Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1999, p. 165

- ^ Younger 2001, p. 36

- OCLC 230674424.

- OCLC 492978278.

- ^ Tambiah 1986, pp. 61–63

- ^ Younger 2001, p. 40

Cited literature

- Bastin, Rohan (2002), The Domain of Constant Excess: Plural Worship at the Munnesvaram Temples in Sri Lanka, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-57181-252-0

- Bechert, Heinz (1970). "Skandakumara and Kataragama: An Aspect of the Relation of Hinduism and Buddhism in Sri Lanka". Proceedings of the Third International Tamil Conference Seminar. Paris: International Association of Tamil Research.

- Clothey, Fred; Ramanujan, A.K. (1978), The many faces of Murukan: the history and meaning of a South Indian god, Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 0-415-34438-7

- Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (2002), Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland: An Encyclopedia, University of California, Santa Barbara, ISBN 978-1-57607-004-8

- Feddema, J.P. (December 1997). "The cursing practice in Sri Lanka as a religious channel for". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 32 (3–4). The Netherlands: E.J. Brill: 202–222. S2CID 144302471.

- Gombrich, Richard Francis; Obeyesekere, Gananath (December 1999), Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0702-2

- Gupta, Suman (2010), Globalization in India: Contents and Discontents, Pearson Education South Asia, ISBN 978-81-317-1988-6

- Holt, John (1991), Buddha in the crown: Avalokiteśvara in the Buddhist traditions of Sri Lanka, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-506418-6

- Kapferer, Bruce (1997), The Feast of the Sorcerer: practices of consciousness and power, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-42413-8

- ISBN 978-0-7914-7081-7

- Paranavitana, Senarath (1933), Epigraphia Zeylanica (PDF), vol. III, Oxford University Press

- Raj, Selva (2006), Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia, State University of New York, ISBN 0-7914-6707-4

- Reynolds, Craig (2006), Seditious histories:contesting Thai and Southeast Asian pasts, University of Washington Press, ISBN 9971-69-335-6

- Tambiah, Stanley (1986), Sri Lanka : ethnic fratricide and the dismantling of democracy, University of Chicago, ISBN 1-85043-026-8

- Wanasundera, Nanda (2004), Cultures of the world: Sri Lanka, Times Books International, ISBN 0-7614-1477-0

- Wirz, Paul (1966), Kataragama:The holiest place in Ceylon, Lake house publishing house, OCLC 9662399

- Womak, Marie (2005), Symbols and Meaning: A Concise Introduction, Altamira Press, ISBN 0-7591-0322-4

- Younger, Paul (2001), Playing Host to Deity: Festival Religion in the South Indian Tradition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-514044-3

External links

- The Kataragama-Skanda website

- Pictures of Kataragama

- Embekke Kataragama temple

- On Foot by Faith to Kataragama

- Official Website – Ruhunu Maha Katharagama Devalaya Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine