Landis's Missouri Battery

| Landis's Battery Landis's Company, Missouri Light Artillery | |

|---|---|

| Engagements | American Civil War |

Landis's Missouri Battery, also known as Landis's Company, Missouri Light Artillery, was an

In 1863, the unit was transferred to

Background

In the United States during the early 19th century, a large cultural divide developed between the

In

Meanwhile, the state of

Two days later, the Missouri State Guard suffered another defeat at the hands of Lyon, this time at the

Service history

1862

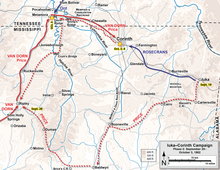

On May 1, while stationed in the vicinity of

Price and Van Dorn then joined forces; Van Dorn commanded the combined army, as he had

The Confederate infantry assaults on October 3 had driven Rosecrans's men from the outer line, but the inner line was still in Union hands.

1863

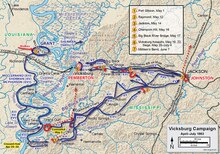

On January 27, 1863, the battery was transferred to

Meanwhile, Grant was faced with a choice: he could approach

The next day, the battery was present at the

See also

Notes

- ^ Archaeological evidence suggests that the battery was likely present,[2] although it is also claimed that the battery was not with the Army of the West during the battle.[3]

- ^ Price's commission was in the Missouri State Guard, not the Confederate States Army.[11]

- ^ Loring never rejoined Pemberton's force.[62]

References

- ^ a b c "Landis's Company, Missouri Light Artillery". National Park Service. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ a b Drexler, Carl G. (May 2018). "Explosive Archeology at Pea Ridge – May Artifact of the Month". Arkansas Archeological Survey. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f McGhee 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Holmes 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Bearss 2007, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Bearss 2007, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 4.

- ^ Bearss 2007, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Bearss 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 11–15.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 20–21, 23.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 20, 25.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, p. 73.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, p. 59.

- ^ Barr 1963, p. 249.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Bevier 1879, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l McGhee 2008, p. 39.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, p. 129.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 129, 131.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 327.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 204.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 219–220.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, p. 131.

- ^ Bevier 1879, p. 152.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 122.

- ^ Wright 1984, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 158.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, p. 192.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 158–160.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, p. 218.

- ^ Ballard 2004, pp. 238–240.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 164.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 151.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 167, 169.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 158.

- ^ Gottschalk 1991, p. 246.

- ^ a b Bevier 1879, p. 191.

- ^ "Order of Battle – Confederate". National Park Service. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Coleman 1903, p. 16.

- ^ a b Tucker 1993, pp. 172–175.

- ^ a b Gottschalk 1991, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 240.

- ^ Kountz 1901, p. 58.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 151.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b Tucker 1993, pp. 178–183.

- ^ Bevier 1879, p. 194.

- ^ Bevier 1879, p. 195.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 188.

- ^ McGhee 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ McGhee 2008, p. 40.

Sources

- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2893-9.

- JSTOR 40007663.

- ISBN 978-1-4262-0093-9.

- OCLC 1166378712.

- Coleman, D. C. (1903). Report of the Commission Appointed by the Governor to Determine the Position of the Missouri Troops at Vicksburg, 1901–1902 (PDF). Jefferson City, Missouri: Tribune Printing Company. OCLC 18496035.

- ISBN 978-0-8078-2320-0.

- Gottschalk, Phil (1991). In Deadly Earnest: The Missouri Brigade. Columbia, Missouri: Missouri River Press. ISBN 978-0-9631136-1-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-866209-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Kountz, John S. (1901). Record of the Organizations Engaged in the Campaign, Siege, and Defense of Vicksburg (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. OCLC 70751401.

- McGhee, James E. (2008). Guide to Missouri Confederate Regiments, 1861–1865. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-870-7.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2012) [2006]. Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-19-7.

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas (1993). The South's Finest: The First Missouri Confederate Brigade From Pea Ridge to Vicksburg. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-942597-31-8.

- Wright, William C. (1984). Archaeological Report No. 13: The Confederate Upper Battery Site, Grand Gulf, Mississippi Excavations 1982 (PDF). Jackson, Mississippi: Mississippi Department of Archives and History. ISBN 978-0-938896-38-8.

External links

- "List of men who served in the battery". Archived from the original on August 7, 2016.