Lernaean Hydra

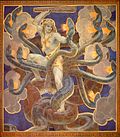

Gustave Moreau's 19th-century depiction of the Hydra, influenced by the Beast from the Book of Revelation | |

| Family | Child of Typhon and Echidna |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Greek mythology |

| Country | Greece |

| Region | Lerna |

The Lernaean Hydra or Hydra of Lerna (

According to Hesiod, the Hydra was the offspring of Typhon and Echidna.[3] It had poisonous breath and blood so virulent that even its scent was deadly.[4] The Hydra possessed many heads, the exact number of which varies according to the source. Later versions of the Hydra story add a regeneration feature to the monster: for every head chopped off, the Hydra would regrow two heads.[5] Heracles required the assistance of his nephew Iolaus to cut off all of the monster's heads and burn the neck using a sword and fire.[6]

Development of the myth

The oldest extant Hydra narrative appears in Hesiod's

Like the initial number of heads, the monster's capacity to regenerate lost heads varies with time and author. The first mention of this ability of the Hydra occurs with

The Hydra had many parallels in

Second Labor of Heracles

Eurystheus, the king of the Tiryns, sent Heracles (or Hercules) to slay the Hydra, which Hera had raised just to slay Heracles. Upon reaching the swamp near Lake Lerna, where the Hydra dwelt, Heracles covered his mouth and nose with a cloth to protect himself from the poisonous fumes. He shot flaming arrows into the Hydra's lair, the spring of Amymone, a deep cave from which it emerged only to terrorize neighboring villages.[9] He then confronted the Hydra, wielding either a harvesting sickle (according to some early vase-paintings), a sword, or his famed club. Heracles then attempted to cut off the Hydra's heads but each time that he did so, one or two more heads (depending on the source) would grow back in its place. The Hydra was invulnerable as long as it retained at least one head.

The struggle is described by the mythographer

The alternate version of this myth is that after cutting off one head he then dipped his sword in its neck and used its venom to burn each head so it could not grow back. Hera, upset that Heracles had slain the beast she raised to kill him, placed it in the dark blue vault of the sky as the constellation Hydra. She then turned the crab into the constellation Cancer.

Heracles would later use arrows dipped in the Hydra's poisonous blood to kill other foes during his remaining labors, such as

When Eurystheus, the agent of Hera who was assigning

Constellation

Greek and Roman writers related that

In art

-

black-figure hydria(c. 346 BC)

-

Mosaic fromRoman Spain(AD 26)

-

Silver sculpture (1530s)

-

Engraving (1) byHans Sebald Beham

-

Gustave Moreau (1861)

-

John Singer Sargent (1921)

-

A modern version by Nikolai Triik

-

Reverse of a 1914 medal by Fritz Eue commemorating General Erich Ludendorff[15]

See also

- Basilisk

- Feathered Serpent

- Horned Serpent

- Prehistoric snakes

- Python (mythology)

- Scylla

- Snakes in mythology

- Titanoboa

Citations

- ^ Kerenyi (1959), p. 143.

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 26.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 310 ff.. See also Hyginus, Fabulae Preface & 151

- ^ According to Hyginus, Fabulae 30, the Hydra "was so poisonous that she killed men with her breath, and if anyone passed by when she was sleeping, he breathed her tracks and died in the greatest torment."

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 29–30.

- ISBN 9781350014886.

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 27–29.

- ^ Ogden 2013, p. 30.

- ^ a b Kerenyi (1959), p. 144.

- Apollodorus, 2.5.2.

- ^ Strabo, 8.3.19

- ^ Pausanias, 5.5.9

- ^ Grimal (1986), p. 219.

- ^ Eratosthenes, Catasterismi.

- ^ "Ludendorff". London: Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

General and cited references

- .

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.

- Grimal, Pierre (1986). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1903). Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Kerenyi, Carl(1959). The Heroes of the Greeks.

- Ogden, Daniel (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199557325.

- Piccardi, Luigi (2005). The head of the Hydra of Lerna (Greece). Archaeopress, British Archaeological Reports, International Series N° 1337/2005, 179-186.

- Staples, Danny(1994). The World of Classical Myth.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 33–34.

- "Statue of Heracles battling the Lernaean Hydra at the southern entrance to the Hofburg (Imperial Palace) in Vienna". Britannica Encyclopaedia.

- "Statue of the Hydra battling Hercules at the Louvre". cartelen.louvre.fr. 1525.

![Reverse of a 1914 medal by Fritz Eue commemorating General Erich Ludendorff[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/Medaillie_General_Erich_Ludendorff_1914_FRZ_EUE_BERLIN.jpg/120px-Medaillie_General_Erich_Ludendorff_1914_FRZ_EUE_BERLIN.jpg)