Constellation

A constellation is an area on the celestial sphere in which a group of visible stars forms a perceived pattern or outline, typically representing an animal, mythological subject, or inanimate object.[1]

The origins of the earliest constellations likely go back to

Twelve (or thirteen) ancient constellations belong to the

In 1922, the

Other star patterns or groups called

Terminology

The word constellation comes from the Late Latin term cōnstellātiō, which can be translated as "set of stars"; it came into use in Middle English during the 14th century.[8] The Ancient Greek word for constellation is ἄστρον (astron). These terms historically referred to any recognisable pattern of stars whose appearance was associated with mythological characters or creatures, earthbound animals, or objects.[1] Over time, among European astronomers, the constellations became clearly defined and widely recognised. Today, there are 88 IAU designated constellations.[9]

A constellation or star that never sets below the

Stars in constellations can appear near each other in the sky, but they usually lie at a variety of distances away from the Earth. Since each star has its own independent motion, all constellations will change slowly over time. After tens to hundreds of thousands of years, familiar outlines will become unrecognizable.[13] Astronomers can predict the past or future constellation outlines by measuring individual stars' common proper motions or cpm[14] by accurate astrometry[15][16] and their radial velocities by astronomical spectroscopy.[17]

Identification

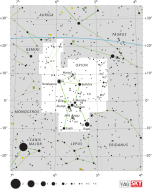

The 88 constellations recognized by the

History of the early constellations

Lascaux Caves, southern France

It has been suggested that the 17,000-year-old cave paintings in Lascaux, southern France, depict star constellations such as Taurus, Orion's Belt, and the Pleiades. However, this view is not generally accepted among scientists.[21][22]

Mesopotamia

Inscribed stones and clay writing tablets from Mesopotamia (in modern Iraq) dating to 3000 BC provide the earliest generally accepted evidence for humankind's identification of constellations.[23] It seems that the bulk of the Mesopotamian constellations were created within a relatively short interval from around 1300 to 1000 BC. Mesopotamian constellations appeared later in many of the classical Greek constellations.[24]

Ancient Near East

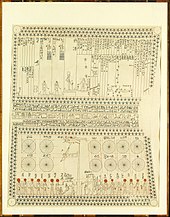

The oldest

The classical Zodiac is a revision of

Biblical scholar

Classical antiquity

There is only limited information on ancient Greek constellations, with some fragmentary evidence being found in the , written in the 2nd century.

In the

Ancient China

Three schools of classical

A well-known map from the Song period is the Suzhou Astronomical Chart, which was prepared with carvings of stars on the planisphere of the Chinese sky on a stone plate; it is done accurately based on observations, and it shows the supernova of the year of 1054 in Taurus.[35]

Influenced by European astronomy during the late Ming dynasty, charts depicted more stars but retained the traditional constellations. Newly observed stars were incorporated as supplementary to old constellations in the southern sky, which did not depict the traditional stars recorded by ancient Chinese astronomers. Further improvements were made during the later part of the Ming dynasty by Xu Guangqi and Johann Adam Schall von Bell, the German Jesuit and was recorded in Chongzhen Lishu (Calendrical Treatise of Chongzhen period, 1628).[clarification needed] Traditional Chinese star maps incorporated 23 new constellations with 125 stars of the southern hemisphere of the sky based on the knowledge of Western star charts; with this improvement, the Chinese Sky was integrated with the World astronomy.[35][36]

Early modern astronomy

Historically, the origins of the constellations of the northern and southern skies are distinctly different. Most northern constellations date to antiquity, with names based mostly on Classical Greek legends.

Some of the early constellations were never universally adopted. Stars were often grouped into constellations differently by different observers, and the arbitrary constellation boundaries often led to confusion as to which constellation a celestial object belonged. Before astronomers delineated precise boundaries (starting in the 19th century), constellations generally appeared as ill-defined regions of the sky.[38] Today they now follow officially accepted designated lines of right ascension and declination based on those defined by Benjamin Gould in epoch 1875.0 in his star catalogue Uranometria Argentina.[39]

The 1603 star atlas "Uranometria" of Johann Bayer assigned stars to individual constellations and formalized the division by assigning a series of Greek and Latin letters to the stars within each constellation. These are known today as Bayer designations.[40] Subsequent star atlases led to the development of today's accepted modern constellations.

Origin of the southern constellations

The southern sky, below about −65°

The history of southern constellations is not straightforward. Different groupings and different names were proposed by various observers, some reflecting national traditions or designed to promote various sponsors. Southern constellations were important from the 14th to 16th centuries, when sailors used the stars for celestial navigation. Italian explorers who recorded new southern constellations include Andrea Corsali, Antonio Pigafetta, and Amerigo Vespucci.[28]

Many of the

Several modern proposals have not survived. The French astronomers

.88 modern constellations

A list of 88 constellations was produced for the International Astronomical Union in 1922.[5] It is roughly based on the traditional Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in his Almagest in the 2nd century and Aratus' work Phenomena, with early modern modifications and additions (most importantly introducing constellations covering the parts of the southern sky unknown to Ptolemy) by Petrus Plancius (1592, 1597/98 and 1613), Johannes Hevelius (1690) and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille (1763),[48][49][50] who introduced fourteen new constellations.[51] Lacaille studied the stars of the southern hemisphere from 1751 until 1752 from the Cape of Good Hope, when he was said to have observed more than 10,000 stars using a refracting telescope with an aperture of 0.5 inches (13 mm).

In 1922,

-

Equirectangular plot of declination vs right ascension of stars brighter than apparent magnitude 5 on theHipparcos Catalogue, coded by spectral type and apparent magnitude, relative to the modern constellations and the ecliptic

The boundaries developed by Delporte used data that originated back to epoch

Symbols

The constellations have no official symbols, though those of the ecliptic may take the signs of the zodiac.[57] Symbols for the other modern constellations, as well as older ones that still occur in modern nomenclature, have occasionally been published.[58]

Dark cloud constellations

The Great Rift, a series of dark patches in the

-

The Emu in the sky – a constellation defined by dark clouds rather than by stars. The head of the emu is the Coalsack with the Southern Cross directly above. Scorpius is to the left.

-

Inca dark cloud constellations in the Mayu (Celestial River), also known as the Milky Way. The Southern Cross is above Yutu, while the eyes of the Llama are Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri.

List of dark cloud constellations

See also

- Celestial cartography

- Constellation family

- Former constellations

- IAU designated constellations

- Lists of stars by constellation

- Constellations listed by Johannes Hevelius

- Constellations listed by Lacaille

- Constellations listed by Petrus Plancius

- Constellations listed by Ptolemy

References

- ^ a b "Definition of constellation". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ "Constellation | Definition, Origin, History, & Facts | Britannica". 5 March 2024.

- S2CID 122004678.

[T]he zodiac was introduced between −408 and −397 and probably within a very few years of −400.

- ^ a b Delporte, Eugène (1930). Délimitation scientifique des constellations. International Astronomical Union.

- ^ a b c Ridpath, Ian (2018). "Star Tales: The final 88".

- ^ "DOCdb Deep Sky Observer's Companion – the online database". Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "A Complete List of Asterisms". Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "constellation | Origin and meaning of constellation by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ "Constellation". Oxford Dictionary of Astronomy. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Harbord, John Bradley; Goodwin, H. B. (1897). Glossary of navigation: a vade mecum for practical navigators (3rd ed.). Portsmouth: Griffin. p. 142.

- ^ a b c Norton, Arthur P. (1959). Norton's Star Atlas. p. 1.

- ^

Steele, Joel Dorman (1884). "The story of the stars: New descriptive astronomy". Science series. American Book Company: 220.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Do Constellations Ever Break Apart or Change?". NASA. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-4387-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-64216-3.

- S2CID 32887246.

- ^ "Resolution C1 on the Definition of a Spectroscopic "Barycentric Radial-Velocity Measure". Special Issue: Preliminary Program of the XXVth GA in Sydney, July 13–26, 2003 Information Bulletin n° 91" (PDF). IAU Secretariat. July 2002. p. 50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ What Are the Constellations?, University of Wisconsin, http://www.astro.wisc.edu/~dolan/constellations/extra/constellations.html

- ^ "Forest for the Trees – Why We Recognize Faces & Constellations". Nautilus Magazine. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ISBN 978-0547132808.

- Bibcode:1997ascu.conf..217R.

- ^ Cunningham, D. (2011). "The Oldest Maps of the World: Deciphering the Hand Paintings of Cueva de El Castillo Cave in Spain and Lascaux in France". Midnight Science. 4: 3.

- ^ Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ^ PMID 17076089.

- ^ "History of the Constellations and Star Names – D.4: Sumerian constellations and star names?". Gary D. Thompson. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ISBN 978-963-527-403-1.

- ISBN 978-1-929626-14-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-486-13766-7.

- ^ "H5906 - ʿayiš - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (KJV)". Blue Letter Bible.

- S2CID 192976174.

- ISBN 978-0-87169-214-6.

- ^ Denderah (1825). Zodiac of Dendera, epitome. (Exhib., Leic. square).

- ISBN 978-0521058018.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Norton, Arthur P. (1919). Norton's Star Atlas. p. 1.

- ^ "Astronomical Epoch". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- S2CID 118829690.

- Bibcode:1951JRASC..45..215S.

- ^ Knobel, E. B. (1917). On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations. (Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 77, pp. 414–32)

- ^ Dekker, Elly (1987). Early Explorations of the Southern Celestial Sky. (Annals of Science 44, pp. 439–70)

- ^ Dekker, Elly (1987). On the Dispersal of Knowledge of the Southern Celestial Sky. (Der Globusfreund, 35–37, pp. 211–30)

- ^ Verbunt, Frank; van Gent, Robert H. (2011). Early Star Catalogues of the Southern Sky: De Houtman, Kepler (Second and Third Classes), and Halley. (Astronomy & Astrophysics 530)

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Johann Bayer's southern star chart". Star Tales.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Lacaille's southern planisphere of 1756". Star Tales.

- ^ a b "The Constellations". IAU – International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Constellation names, abbreviations and sizes". Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Star Tales – The Almagest". Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Nicolas Louis de Lacaille at the Cape". Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "The original names and abbreviations for constellations from 1922". Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "Constellation boundaries". Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-521-80040-2.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Benjamin Apthorp Gould and the Uranometria Argentina". Star Tales.

- ^ A.C. Davenhall & S.K. Leggett, "A Catalogue of Constellation Boundary Data", (Centre de Donneés astronomiques de Strasbourg, February 1990).

- ^ For example, in the Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the year 1833 (Board of Admiralty, London)

- ^ Peter Grego (2012) The Star Book: Stargazing Throughout the Seasons in the Northern Hemisphere. F+W Media.

- ^ Rao, Joe (11 September 2009). "A Great Week to See the Milky Way". Space. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Night sky". Astronomy.pomona.edu. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Bibcode:1983JHAS...14...37D.

- ISBN 978-0486428826.

- ISBN 978-1-4614-0929-8.

Further reading

This 'further reading' section may need cleanup. (August 2016) |

Mythology, lore, history, and archaeoastronomy

- ISBN 978-0-486-21079-7softcover.

- ISBN 978-0-486-43581-7softcover.

- Kelley, David H. and Milone, Eugene F. (2004) Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-95310-6hardcover.

- ISBN 978-0-718-89478-8softcover.

- Staal, Julius D. W. (1988) The New Patterns in the Sky: Myths and Legends of the Stars, McDonald & Woodward Publishing Co., ISBN 0-939923-04-1softcover.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108: 79–89. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

Atlases and celestial maps

General and nonspecialized – entire celestial heavens

- Becvar, Antonin. Atlas Coeli. Published as Atlas of the Heavens, Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, MA, with coordinate grid transparency overlay.

- Norton, Arthur Philip. (1910) ISBN 978-0-13-145164-3, hardcover.

- National Geographic. Forerunner map as A Map of The Heavens, as a special supplement to the December 1957 issue. Current version 2001 (Tirion), with 2007 reprint.

- Sinnott, Roger W. and Perryman, Michael A.C. (1997) ISBN 0-933346-83-2hardcover. Softcover version available. Supplemental separate purchasable coordinate grid transparent overlays.

- ISBN 978-0-943396-73-6, hardcover, printed boards.

- Tirion, Wil and Sinnott, Roger W. (1998) Sky Atlas 2000.0, various editions. 2nd Deluxe Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

Northern celestial hemisphere and north circumpolar region

- ISBN 0-933346-01-8oversize folio softcover spiral-bound, with transparency overlay coordinate grid ruler.

Equatorial, ecliptic, and zodiacal celestial sky

- Becvar, Antonin. (1958) Atlas Eclipticalis 1950.0, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Praha, Czechoslovakia, 1st Edition, elephant folio hardcover, with small transparency overlay coordinate grid square and separate paper magnitude legend ruler. 2nd Edition 1974, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Prague, Czechoslovakia, and Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, MA, oversize folio softcover spiral-bound, with transparency overlay coordinate grid ruler.

Southern celestial hemisphere and south circumpolar region

- Becvar, Antonin. Atlas Australis 1950.0, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Praha, Czechoslovakia, 1st Edition, hardcover, with small transparency overlay coordinate grid square and separate paper magnitude legend ruler. 2nd Edition, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (Ceskoslovenske Akademie Ved), Prague, Czechoslovakia, and Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, MA, oversize folio softcover spiral-bound, with transparency overlay coordinate grid ruler.

Catalogs

- Becvar, Antonin. (1959) Atlas Coeli II Katalog 1950.0, Praha, 1960 Prague. Published 1964 as Atlas of the Heavens – II Catalogue 1950.0, Sky Publishing Corporation, Cambridge, MA

- Hirshfeld, Alan and Sinnott, Roger W. (1982) Sky Catalogue 2000.0, Cambridge University Press and Sky Publishing Corporation, 1st Edition, 2 volumes. ISBN 0-521-27721-3(Cambridge) softcover and 0-933346-38-7 softcover – reprint of 1985 edition.

- Louise F. Jenkins. 3rd Edition (1964), 4th Edition, 5th Edition (1991), and 6th Edition (pending posthumous) by Hoffleit.

External links

- IAU: The Constellations, including high quality maps.

- Atlascoelestis, di Felice Stoppa.

- Celestia free 3D realtime space-simulation (OpenGL)

- Stellarium realtime sky rendering program (OpenGL)

- Strasbourg Astronomical Data Center Files on official IAU constellation boundaries

- Studies of Occidental Constellations and Star Names to the Classical Period: An Annotated Bibliography

- Table of Constellations

- Online Text: Hyginus, Astronomica translated by Mary Grant Greco-Roman constellation myths

- Neave Planetarium Adobe Flash interactive web browser planetarium and stardome with realistic movement of stars and the planets.

- Audio – Cain/Gay (2009) Astronomy Cast Constellations

- The Greek Star-Map short essay by Gavin White

- Bucur D. The network signature of constellation line figures. PLOS ONE 17(7): e0272270 (2022). A comparative analysis on the structure of constellation line figures across 56 sky cultures.