New Korean Orthography

| New Korean Orthography | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 조선어신철자법 |

|---|---|

| Hancha | 朝鮮語新綴字法 |

| Revised Romanization | Joseoneo sincheoljabeop |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chosŏnŏ sinch’ŏlchapŏp |

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

|

The New Korean Orthography was a spelling reform used in North Korea from 1948 to 1954. It added five consonants and one vowel letter to the Hangul alphabet, supposedly making it a more morphophonologically "clear" approach to the Korean language.

History

After the establishment of the

In 1948, the New Korean Orthography was promulgated, along with the Standard Language Orthography Dictionary.

Contents

The reason for the reform is that some Korean roots change form and therefore cannot be written with a consistent spelling using standard hangul. The additional letters introduced in the New Orthography do not represent new sounds, but these situations where a sound changes, say from a /p/ to a /w/. Three were created de novo by modifying existing letters, two (ㅿ and ㆆ) were obsolete letters, and one (![]() ) is a numeral.

) is a numeral.

For example, the root of the verb "to walk" has the form 걷 kŏt- before a consonant, as in the inflection 걷다 kŏtta, but the form 걸 kŏl- before a vowel, as in 걸어 kŏrŏ and 걸으니 kŏrŭni. In New Orthography, the root is an invariable 거ᇫ, spelled with the new letter ㅿ in place of both the ㄷ in 걷 and the ㄹ in 걸: 거ᇫ다 kŏtta, 거ᇫ어 kŏrŏ.

Another example is the root of the verb "to heal", which has the form 낫 nas- before a consonant, as in 낫다 natta, but the form 나 before a vowel, as in 나아 naa. In some cases, there is an epenthetic ŭ vowel before a consonant suffix, as in 나을 naŭl. In New Orthography, this variable root is written as an invariable 나ᇹ, and the epenthetic vowel is not written: 나ᇹ다 NA’.TA for 낫다 natta, 나ᇹᄅ NA’.L for 나을 naŭl, 나ᇹ아 NA’.A for 나아 naa.

| Letter | Pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|

| before a vowel |

before a consonant | |

| /l/ | —[1] | |

| /nn/ | /l/ | |

| ㅿ | /l/ | /t/ |

| ㆆ | —[2] | /◌͈/[3] |

| /w/[4] | /p/ | |

| /j/[5] | /i/ | |

As with all letters in North Korea, the names follow the formula CiŭC. For convenience they are also called 여린리을 (soft riŭl), 된리을 (strong riŭl), 반시읏 (semi-siŭt), 여린히읗 (soft hiŭt), 위읍 (wiŭp), and 여린이(soft i).

The New Orthography also added two new digraphs to the lexicon, ㅭ /lʔ/ and ᇬ /ŋk/.

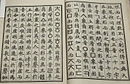

There were other changes that made the orthography more morphemic, without requiring the addition of new letters. For example, in the word normally spelled 놉니다 (top example in image at right), the politeness morpheme ㅂ is separated out in its own block. Such spellings can be found in medieval documents, but were not normally seen in the 20th century.

The attributive ㄴ n morpheme at the ends of adjectives is also placed in a separate block, and the occasional epenthetic ŭ that appears before it is not written, unlike standard 은 ŭn. A morphemic h is retained before this ending: 하얗다 HA.YAH.TA hayata "is white", 하얗ㄴ HA.YAH.N hayan "white" (standard 하얀 HA.YAN). 좋다 JOH.TA jota "is good", 좋ㄴ JOH.N johŭn "good" (standard 좋은 JOH.ŬN).

See also

- Revised Romanization

Notes

- ^ Silence

- ^ Makes the following consonant tense, as a final ㅅ does

- ^ In standard orthography, combines with a following vowel as ㅘ, ㅙ, ㅚ, ㅝ, ㅞ, ㅟ

- ^ In standard orthography, combines with a following vowel as ㅑ, ㅒ, ㅕ, ㅖ, ㅛ, ㅠ

References

- ^ a b c d e f Fishman, Joshua; Garcia, Ofelia (2011). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 156–158.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaplan & Baldauf (2003). Language and Language-in-Education Planning in the Pacific Basin. pp. 39–44.

- ^ a b c King (1997). "Language, Politics, and Ideology in the Postwar Koreas". In McCann (ed.). Korea Briefing: Toward Reunification. pp. 124–126, 128.

- ^ Kim, Sun Joo, ed. (2010). The Northern Region of Korea: History, Identity, and Culture. University of Washington Press. pp. 171–172.

- Kaplan, R.B.; Baldauf Jr., Richard B. (2003). Language and language-in-education planning in the Pacific Basin. Springer.

- King, Ross (1997). "Language, Politics, and Ideology in the Postwar Koreas". In McCann, David R. (ed.). Korea briefing: toward reunification. M.E. Sharpe.