No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit RAAF

| No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit RAAF | |

|---|---|

No. 2 OCU's crest | |

| Active | 1942–1947 1952–current |

| Country | Australia |

| Branch | Royal Australian Air Force |

| Role | Operational conversion Refresher courses Fighter combat instruction |

| Part of | No. 81 Wing |

| Garrison/HQ | RAAF Base Williamtown |

| Motto(s) | Juventus Non Sine Pinnis ("The Young Shall Have Wings") |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Peter Jeffrey (1942–1943, 1944–1946) Wilfred Arthur (1944) Dick Cresswell (1953–1956) Neville McNamara (1959–1961) |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Fighter | Lockheed Martin F-35A Lightning II |

No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit (No. 2 OCU) is a fighter training unit of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Located at RAAF Base Williamtown, New South Wales, the unit trains pilots to operate the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II. Pilots new to the F-35 enter No. 2 2OCU after first qualifying to fly fast jets at No. 79 Squadron and undertaking initial fighter combat instruction at No. 76 Squadron. Once qualified on the F-35, they are posted to one of No. 81 Wing's operational F-35 units, No. 3 Squadron, No. 75 Squadron or No. 77 Squadron.

The unit was established as No. 2 (Fighter) Operational Training Unit (No. 2 OTU) in April 1942 at

Role and equipment

The role of No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit (No. 2 OCU) is to "support the preparation for and the conduct of effective airspace control, counter air strike and combat air support operations through the provision of trained personnel".[1] Located at RAAF Base Williamtown, New South Wales, it comes under the control of No. 81 Wing, part of Air Combat Group.[1][2]

No. 2 OCU is primarily responsible for conducting operational conversion courses on the RAAF's fifth generationLockheed Martin F-35A Lightning II fighter, which entered service in 2019. The unit takes students who have converted to fast jets with No. 79 Squadron, located at RAAF Base Pearce, Western Australia, and undergone lead-in fighter training at No. 76 Squadron, based at Williamtown.[1][3] Most are new to operational flying, but some are "retreads" (experienced pilots converting from another aircraft type).[4] No. 2 OCU's instructors are among the RAAF's most experienced pilots, and often play a major role developing new tactics, in co-operation with fighter combat instructors at other No. 81 Wing units.[5]

No. 2 OCU operates the F-35As, the conventional takeoff and landing (

Prior to 2019, when 2OCU operated F/A-18s, the Hornet conversion courses ran for six months, after which graduates were posted to one of the RAAF's front-line fighter units, No. 3 Squadron or No. 77 Squadron at Williamtown, or No. 75 Squadron at RAAF Base Tindal, Northern Territory.[6][10] Students first gained their instrument rating on the Hornet, and then taught basic fighter manoeuvres, air combat techniques, air-to-air gunnery, and air-to-ground tactics.[4][5] The course culminates with Exercise High Sierra, a biannual event that was first run at Townsville, Queensland, in 1986.[5][9] The exercise lasted several weeks and involved day and night flights, including precision strike sorties with practice and live bombs.[10][11]

As well as operational conversion, No. 2 OCU conducted refresher courses and fighter combat instructor courses.[1] Pilots who had not flown Hornets for more than nine months undertook the two-week refresher course.[12] Fighter combat instructor courses run for five months and are given every two years.[1][13] Students were chosen from among the most experienced Hornet squadron pilots and undertook instruction in how to train others, as well as how to deal with complex operational scenarios.[4] This was tested in simulated combat with other types of US or RAAF aircraft, as available, including F-15 Eagles, F-16 Fighting Falcons, and F/A-18 Super Hornets.[4][13] Graduates became qualified F/A-18 instructors and remained with No. 2 OCU for the next two-year cycle. After this time, they were posted to one of the front-line squadrons or No. 81 Wing's headquarters as Hornet weapons-and-tactics specialists.[5] Along with training pilots, No. 2 OCU were occasionally called upon to conduct operational tasks in certain circumstances.[14]

History

Operational training: 1942–1947

During World War II, the RAAF established several operational training units (OTUs) to convert recently graduated pilots from advanced trainers to combat aircraft, and to add fighting techniques to the flying skills they had already learned.

No. 2 OTU's Spitfire section was transferred to RAAF Station Williamtown, New South Wales, in March 1943, under the command of ace John Waddy.[9][21] Jeffrey handed over command of No. 2 OTU at Mildura in August 1943; the same month, the unit logged over 5,000 flying hours, its highest level during the war. For the remainder of the conflict it maintained an average strength of more than 100 aircraft.[9] North African campaign aces and former No. 3 Squadron commanders Bobby Gibbes and Nicky Barr served successively as chief flying instructor from March 1944 until the end of the Pacific War.[22][23] Group Captain Arthur led the unit from July to November 1944, when Group Captain Jeffrey resumed command.[9] During 1945, the Spitfires and Kittyhawks were replaced by 32 North American P-51 Mustangs.[24] Training concluded that October, following the cessation of hostilities, and No. 2 OTU was reduced to a care-and-maintenance unit.[1][9] During the war, it had graduated 1,247 pilots, losing 45 students in fatal accidents.[9] Jeffrey completed his appointment in June 1946, and the unit was disbanded on 25 March 1947.[9][25]

Operational training: 1952–1958

Post-war demobilisation saw the disbandment of all the RAAF's OTUs.[9][15] Operational conversion of new pilots then became the responsibility of front-line squadrons. This practice disrupted the squadrons' normal duties, and the advent of the Korean War and the introduction of jet aircraft further necessitated a more formal system of operational training.[15] According to Dick Cresswell, commanding officer of No. 77 Squadron in Korea from September 1950 to August 1951:[26]

It is hard to believe that I actually sent 11 pilots home to Australia as they were not capable of doing the job properly. I don't blame the pilots, but I do blame the Air Force system. We had no operational training units, no operational training system and, as a result, the pilots came to Korea poorly trained and without instrument ratings. They just couldn't operate in the area.

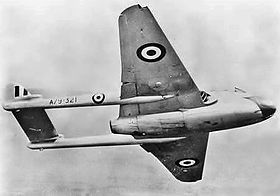

The RAAF moved to rectify the situation by re-forming No. 2 OTU on 1 March 1952 to convert RAAF pilots to jet aircraft and train them for fighter operations.[15] Headquartered at RAAF Base Williamtown, it was equipped with Wirraways, Mustangs, and de Havilland Vampire jets.[9][27] Cresswell took command of No. 2 OTU on 21 May 1953. The unit ceased flying Mustangs that October, retaining its Wirraways and Vampires. In April 1954, it began conducting fighter combat instructor courses, as well as refresher courses on jets.[9] Cresswell delivered the first Australian-built CAC Sabre jet fighter to No. 2 OTU in November, and the same month established the unit's Sabre Trials Flight.[9][28] The flight was responsible for performance testing and developing combat flying techniques, in concert with the Aircraft Research and Development Unit (ARDU).[29] On 3 December 1954, Creswell led a formation of twelve No. 2 OTU Vampires in the shape of two sevens over Sydney to greet No. 77 Squadron upon its arrival from service in Korea aboard the aircraft carrier HMAS Vengeance.[30] Training courses on the Sabre began on 1 January 1955.[9] Once the Sabre entered operational service in March 1956, the Sabre Trials Flight was dissolved and its responsibilities passed to No. 3 Squadron.[29] Pilots underwent their introduction to jets and fighter combat at No. 2 OTU, but finished their conversion to Sabres at a front-line squadron.[15]

Operational conversion: 1958–current

In May 1958, No. 1 Applied Flying Training School began equipping with Vampire jet trainers at RAAF Base Pearce, Western Australia.[31] As RAAF pilots were now gaining their first exposure to jets elsewhere, No. 2 OTU took over from the fighter squadrons the responsibility of converting trained jet pilots to Sabres.[15] Reflecting its new primary role, it was renamed No. 2 (Fighter) Operational Conversion Unit (No. 2 OCU) in September 1958, and ceased Vampire courses the same month.[9][15] Wing Commander Neville McNamara, later Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) and Chief of the Defence Force Staff, served as commanding officer from August 1959 until January 1961.[9][32] During his tenure, the unit undertook exercises with No. 75 Squadron at RAAF Bases Amberley, Townsville and Darwin.[33] Two Sabre pilots from No. 2 OCU and one from No. 75 Squadron died in separate incidents early in 1960; each had attempted to eject at low level and suffered fatal head injuries from colliding with the aircraft's canopy during the ejection sequence. All RAAF Sabres were grounded until ARDU developed a modification to shatter the canopy immediately before the pilot ejected.[33][34]

Along with Nos. 75 and 76 Squadrons, also based at Williamtown, No. 2 OCU was under the control of No. 81 Wing from 1961 until the wing was disbanded in 1966.[35][36] By late 1963, personnel were busy developing training material for the pending Sabre replacement, the Dassault Mirage III, a task that required them to translate the manufacturer's technical documentation from the original French.[37][38] No. 2 OCU received its first Mirages in February and March 1964.[37] It commenced conversion courses on the type that October, and fighter combat instructor courses in August 1968.[38] The RAAF eventually took delivery of 100 Mirage IIIO single-seat fighters and 16 Mirage IIID two-seat trainers; No. 2 OCU operated both models.[39] Squadron Leader John Newham, later to serve as CAS, held temporary command of the unit from July 1965 to April 1966.[40][41] A Sabre-equipped aerobatic display team named the "Marksmen" was formed within No. 2 OCU during 1966 and 1967.[42] Between 1967 and 1984, six of the unit's Mirages suffered major accidents, resulting in three fatalities.[39] Experience in the Vietnam War led the RAAF to begin training Forward air controllers in 1968. The task initially fell to No. 2 OCU before a specialised unit, No. 4 Forward Air Control Flight, was formed in 1970.[43] In October 1969, the OCU began operating the Macchi MB-326 jet for lead-in fighter training, as well as the Mirage.[9] No. 5 Operational Training Unit, based at Williamtown, took over responsibility for Macchi courses from April 1970 until its disbandment in July the following year; the Macchis were then transferred back to No. 2 OCU.[9][44]

In preparation for the introduction of the F/A-18 Hornet, No. 2 OCU temporarily ceased flying operations on 1 January 1985 and transferred Macchi and Mirage training to No. 77 Squadron, which assumed responsibility for fighter combat instructor, introductory fighter, and Mirage conversion courses.[9][45] Beginning on 17 May, the first fourteen Australian Hornets—seven single-seat F/A-18As and seven two-seat F/A-18Bs—and a Hornet simulator were delivered to No. 2 OCU. Conversion courses on the type commenced on 19 August with four F/A-18Bs and three students.[6][46] No. 2 OCU has remained the prime user of the two-seat Hornet, though some are operated by the fighter squadrons, Nos. 3, 75 and 77.[6] The first year of Hornet service saw No. 2 OCU, as the then-only RAAF operator, undertake demonstration flights around the country to unveil the new fighter to the Australian public.[47] All of the Hornet units came under the control of a newly re-formed No. 81 Wing on 2 February 1987.[6][36] An intense training program that year resulted in 21 pilots converting to the type.[47] In June 1987, Macchi training courses again became the responsibility of No. 2 OCU; this role was taken over by No. 76 Squadron in January 1989.[9] No. 2 OCU suffered its only Hornet loss to date when an F/A-18B crashed at Great Palm Island, Queensland, during a night-time training flight on 18 November 1987, killing the pilot. Two Hornets collided during an air-to-air combat training exercise the previous year, but both managed to return to base.[48] The unit temporarily relocated to RAAF Base Richmond, New South Wales, in July 1990, while Williamtown's runway was resurfaced.[49]

The RAAF began modifying four of its

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f "No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit". Royal Australian Air Force. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "RAAF Base Williamtown". Royal Australian Air Force. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ ANAO, Tactical Fighter Operations, p. 43

- ^ a b c d e "Training Australia's fighter pilots". Air Force Today. Vol. 1, no. 3. February 1997. pp. 19–22.

- ^ a b c d e f Frawley, Gerard (September 2005). "Hornet Wings". Australian Aviation. No. 220. pp. 50–55.

- ^ a b c d e "F/A-18 Hornet". RAAF Museum. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service, pp. 130–131

- ^ "Crests tell history". RAAF News. Vol. 4, no. 11. December 1962. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v RAAF Historical Section, Training Units, pp. 62–64

- ^ Australian Aviation. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Australia's first female fighter pilots graduate". Australian Aviation. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ ANAO, Developing Air Force's Combat Aircrew, p. 28

- ^ a b "Students take to the sky". Royal Australian Air Force. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Horner, Making the Australian Defence Force, p. 210

- ^ a b c d e f g Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 167–168, 364

- ^ a b Garrisson, Australian Fighter Aces, pp. 142–143

- ^ Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 139–141

- ^ Alexander, Clive Caldwell, p. 99

- ^ Wilson, The Spitfire, Mustang and Kittyhawk in Australian Service, p. 140

- ^ Wilson, The Spitfire, Mustang and Kittyhawk in Australian Service, pp. 142–143

- ^ Newton, Australian Air Aces, pp. 114–115

- ^ Chisholm, Who's Who in Australia, p. 361

- ^ Dornan, Nicky Barr, pp. 94–95, 263–266

- ^ Wilson, The Spitfire, Mustang and Kittyhawk in Australian Service, p. 102

- ^ "Jeffrey, Peter". World War 2 Nominal Roll. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Odgers, Mr Double Seven, pp. xiii, 150

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, p. 489

- ^ Odgers, Mr Double Seven, p. 156

- ^ a b Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 348–349

- ^ Odgers, Mr Double Seven, p. 153

- ^ RAAF Historical Section, Training Units, pp. 40–42

- ^ "Air Chief Marshals". Air Marshals of the RAAF. Air Power Development Centre. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ a b McNamara, The Quiet Man, pp. 117–118

- ^ "Canopy believed cause of Sabre pilot deaths". The Canberra Times. Canberra: National Library of Australia. 19 April 1960. p. 3. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 350, 489

- ^ a b "81WG: then and now". RAAF News. Vol. 36, no. 6. July 1994. p. 15.

- ^ a b Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, pp. 40–41

- ^ a b Stephens, Going Solo, p. 358

- ^ a b Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, pp. 155–158; 165

- ^ Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, p. 142

- ^ "Air Marshals". Air Marshals of the RAAF. Air Power Development Centre. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ McLaughlin, Hornets Down Under, p. 76

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, p. 485

- ^ RAAF Historical Section, Training Units, pp. 71–73

- ^ Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, pp. 90, 107

- ^ Wilson, Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service, p. 116

- ^ a b Wilson, Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service, p. 118

- ^ Wilson, Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service, p. 124

- ^ Wilson, Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service, p. 119

- ^ RAAF Historical Section, Maritime and Transport Units, pp. 38–40

- ^ Liebert, Simone (17 July 2003). "Cloudy day, bright outlook". Air Force. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Peacock; Jackson, Jane's World Air Forces, p. 19

- ^ "Defence Annual Report 2006–07: ADF Units and Establishments" (PDF). Department of Defence. pp. 429–430. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ "No. 81 Wing". Royal Australian Air Force. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Friend, Cath (18 July 2013). "An integrated fighter force". Air Force. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Stephanie (19 April 2018). "Rising to the challenge". Air Force. Vol. 60, no. 6. p. 3. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Lap of honour for hometown Hornets". Media release. Department of Defence. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Payne, Jacqui (19 March 2020). "Bringing it back to home base" (PDF). Air Force. Department of Defence. p. 4. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

References

- Alexander, Kristen (2006). Clive Caldwell: Air Ace. Crows Nest, New South Wales: ISBN 1-74114-705-0.

- ISBN 0-642-44266-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on 19 March 2012.

- ANAO (2004). Developing Air Force's Combat Aircrew: Department of Defence (PDF). Canberra: ANAO. ISBN 0-642-80777-9. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 March 2012.

- Chisholm, Alec H., ed. (1947). OCLC 221679476.

- Dornan, Peter (2005) [2002]. Nicky Barr: An Australian Air Ace. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-529-5.

- Garrisson, A.D. (1999). Australian Fighter Aces 1914–1953. Fairbairn, Australian Capital Territory: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26540-2. Archived from the originalon 24 November 2016.

- ISBN 0-19-554117-0.

- McLaughlin, Andrew (2005). Hornets Down Under. Fyshwick, Australian Capital Territory: Phantom Media. ISBN 0-646-44398-4.

- ISBN 1-920800-07-7. Archived from the originalon 12 May 2014.

- Newton, Dennis (1996). Australian Air Aces. Fyshwyck, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-25-0.

- ISBN 978-1-920800-30-7.

- Peacock, Lindsay; Jackson, Paul (2001). Jane's World Air Forces. Surrey: ISBN 0-7106-1293-1.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 4: Maritime and Transport Units. Canberra: ISBN 0-644-42796-5.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 8: Training Units. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42800-7.

- Stephens, Alan (1995). Going Solo: The Royal Australian Air Force 1946–1971. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42803-1.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Susans, M.R., ed. (1990). The RAAF Mirage Story. RAAF Base Point Cook, Victoria: ISBN 0-642-14835-X.

- Wilson, Stewart (1988). The Spitfire, Mustang and Kittyhawk in Australian Service. Curtin, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 0-9587978-1-1.

- Wilson, Stewart (1993). Phantom, Hornet and Skyhawk in Australian Service. Weston Creek, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 1-875671-03-X.