Ottonian art

Ottonian art is a

After the decline of the Carolingian Empire, the Holy Roman Empire was re-established under the Saxon Ottonian dynasty. From this emerged a renewed faith in the idea of Empire and a reformed Church, creating a period of heightened cultural and artistic fervour. It was in this atmosphere that masterpieces were created that fused the traditions from which Ottonian artists derived their inspiration: models of Late Antique, Carolingian, and Byzantine origin. Surviving Ottonian art is very largely religious, in the form of illuminated manuscripts and metalwork, and was produced in a small number of centres for a narrow range of patrons in the circle of the Imperial court, as well as important figures in the church. However much of it was designed for display to a wider public, especially of pilgrims.[3]

The style is generally grand and heavy, sometimes to excess, and initially less sophisticated than the Carolingian equivalents, with less direct influence from Byzantine art and less understanding of its classical models, but around 1000 a striking intensity and expressiveness emerge in many works, as "a solemn monumentality is combined with a vibrant inwardness, an unworldly, visionary quality with sharp attention to actuality, surface patterns of flowing lines and rich bright colours with passionate emotionalism".[4]

Context

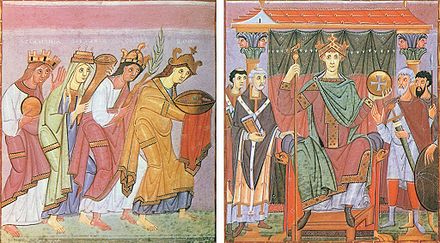

Following late Carolingian styles, "

As well as the reuse of motifs from older imperial art, the removal of

. The one thing the ruler portraits rarely attempt is a close likeness of the individual features of a ruler; when Otto III died, some manuscript images of him were re-purposed as portraits of Henry II without the need being felt to change the features.In a continuation and intensification of late Carolingian trends, many miniatures contain

-

Otto II, by theGregory Master

-

Apotheosis of Otto III. Liuthar Gospels

-

Henry II being crowned by Christ, from the Sacramentary of Henry II

-

Otto III or Henry II crowned by saints, Bamberg Apocalypse

Manuscripts

Ottonian monasteries produced many magnificent medieval illuminated manuscripts. They were a major art form of the time, and monasteries received direct sponsorship from emperors and bishops, having the best in equipment and talent available.[11] The range of heavily illuminated texts was very largely restricted (unlike in the Carolingian Renaissance) to the main liturgical books, with very few secular works being so treated.[2]

In contrast to manuscripts of other periods, it is very often possible to say with certainty who commissioned or received a manuscript, but not where it was made. Some manuscripts also include relatively extensive cycles of narrative art, such as the sixteen pages of the Codex Aureus of Echternach devoted to "strips" in three tiers with scenes from the life of Christ and his parables.[12] Heavily illuminated manuscripts were given rich treasure bindings and their pages were probably seen by very few; when they were carried in the grand processions of Ottonian churches it seems to have been with the book closed to display the cover.[13]

The Ottonian style did not produce surviving manuscripts from before about the 960s, when books known as the "

A number of important manuscripts produced from this period onwards in a distinctive group of styles are usually attributed to the scriptorium of the

The most important "Reichenau school" manuscripts are agreed to fall into three distinct groups, all named after scribes whose names are recorded in their books.[17] The "Eburnant group" covered above was followed by the "Ruodprecht group" named after the scribe of the Egbert Psalter; Dodwell assigns this group to Trier. The Aachen Gospels of Otto III, also known as the Liuthar Gospels, give their name to the third "Liuthar group" of manuscripts, most from the 11th century, in a strongly contrasting style, though still attributed by most scholars to Reichenau, but by Dodwell also to Trier.[18]

The outstanding miniaturist of the "Ruodprecht group" was the so-called Master of the

The style of the "Liuthar group" is very different, and departs further from rather than returning to classical traditions; it "carried transcendentalism to an extreme", with "marked schematization of the forms and colours", "flattened form, conceptualized draperies and expansive gesture".[21] Backgrounds are often composed of bands of colour with a symbolic rather than naturalistic rationale, the size of figures reflects their importance, and in them "emphasis is not so much on movement as in gesture and glance", with narrative scenes "presented as a quasi-liturgical act, dialogues of divinity".[22] This gestural "dumb-show [was] soon to be conventionalized as a visual language throughout medieval Europe".[4]

The group were produced perhaps from the 990s to 1015 or later, and major manuscripts include the Munich Gospels of Otto III, the Bamberg Apocalypse and a volume of biblical commentary there, and the Pericopes of Henry II, the best known and most extreme of the group, where "the figure-style has become more monumental, more rarified and sublime, at the same time thin in density, insubstantial, mere silhouettes of colour against a shimmering void".[23] The group introduced the background of solid gold to Western illumination.

Two dedication miniatures added to the

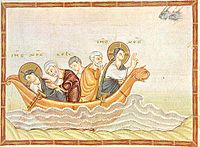

Gallery of Christ calming the storm

This scene was often included in Ottonian cycles of the Life of Christ. Many show Jesus (with crossed halo) twice, once asleep and once calming the storm.

-

Codex Egberti, between 977 and 993

-

Wall-painting at Oberzell, c. 1000

-

Munich Gospels of Otto III; below, the Exorcism of the Gadarene swine

-

Hitda Codex, Cologne, after 1000

Metalwork and enamels

Objects for decorating churches such as crosses,

Examples of

Large objects in non-precious metals were also made, with the earliest surviving

Around 980, Archbishop Egbert of Trier seems to have established the major Ottonian workshop producing

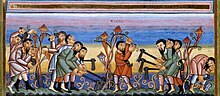

Gallery of bronzes

-

Abbess Mathilde's candelabrum inEssen Cathedral, c. 1000

-

Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Bernward Doors at Hildesheim Cathedral

-

Bernward's doors at Hildesheim Cathedral, c. 1015

-

The bronze Bernward Column at Hildesheim

Ivory carving

Much very fine small-scale sculpture in ivory was made during the Ottonian period, with Milan probably a site if not the main centre, along with Trier and other German and French sites. There are many oblong panels with reliefs which once decorated book-covers, or still do, with the Crucifixion of Jesus as the most common subject. These and other subjects very largely continue Carolingian iconography, but in a very different style.[40]

A group of four Ottonian ivory

Among various stylistic groups and putative workshops that can be detected, that responsible for pieces including the panel from the cover of the Codex Aureus of Echternach and two diptych wings now in Berlin (all illustrated below) produced particularly fine and distinctive work, perhaps in Trier, with "an astonishing perception of the human form ... [and] facility in handling the material".[48]

A very important group of

-

The Basilewsky Situla

-

Diptych panels of Moses Receiving the Law and Doubting Thomas

-

Panel from the cover of the Codex Aureus of Echternach, probably from the same workshop as the diptych.

-

Crucifixion, probably from a book-cover, c 1000

Wall painting

Although it is clear from documentary records that many churches were decorated with extensive cycles of wall-painting, survivals are extremely rare, and more often than not fragmentary and in poor condition. Generally they lack evidence to help with dating such as donor portraits, and their date is often uncertain; many have been restored in the past, further complicating the matter. Most survivals are clustered in south Germany and around Fulda in Hesse; though there are also important examples from north Italy.[51] There is a record of bishop Gebhard of Constance hiring lay artists for a now vanished cycle at his newly foundation (983) of Petershausen Abbey, and laymen may have dominated the art of wall-painting, though perhaps sometimes working to designs by monastic illuminators. The artists seem to have been rather mobile: "at about the time of the Oberzell pictures there was an Italian wall-painter working in Germany, and a German one in England".[52]

The church of St George at Oberzell on Reichenau Island has the best-known surviving scheme, though much of the original work has been lost and the remaining paintings to the sides of the nave have suffered from time and restoration. The largest scenes show the miracles of Christ in a style that both shows specific Byzantine input in some elements, and a closeness to Reichenau manuscripts such as the Munich Gospels of Otto III; they are therefore usually dated around 980–1000. Indeed, the paintings are one of the foundations of the case for Reichenau Abbey as a major centre of manuscript painting.[53]

Larger sculpture

Very little wood carving has survived from the period, but the monumental painted figure of Christ on the

-

Ciborium of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan; note the rods for curtains. The columns are probably 4th century, the canopy 9th, 10th or 12th century.

-

Cross of the Abbess Raingarda, 963- 965, silver, 201x156 cm, Pavia, Basilica of San Michele Maggiore.

Survival and historiography

Surviving Ottonian works are very largely those in the care of the church which were kept and valued for their connections with either royal or church figures of the period. Very often the jewels in metalwork were pilfered or sold over the centuries, and many pieces now completely lack them, or have modern glass paste replacements. As from other periods, there are many more surviving ivory panels (whose material is usually hard to re-use) for book-covers than complete metalwork covers, and some thicker ivory panels were later re-carved from the back with a new relief.[58] Many objects mentioned in written sources have completely disappeared, and we probably now only have a tiny fraction of the original production of reliquaries and the like.[2] A number of pieces have major additions or changes made later in the Middle Ages or in later periods. Manuscripts that avoided major library fires have had the best chance of survival; the dangers facing wall-paintings are mentioned above. Most major objects remain in German collections, often still church libraries and treasuries.

The term "Ottonian art" was not coined until 1890, and the following decade saw the first serious studies of the period; for the next several decades the subject was dominated by German art historians mainly dealing with manuscripts,[59] apart from Adolph Goldschmidt's studies of ivories and sculpture in general. A number of exhibitions held in Germany in the years following World War II helped introduce the subject to a wider public and promote the understanding of art media other than manuscript illustrations. The 1950 Munich exhibition Ars Sacra ("sacred art" in Latin) devised this term for religious metalwork and the associated ivories and enamels, which was re-used by Peter Lasko in his book for the Pelican History of Art, the first survey of the subject written in English, as the usual art-historical term, the "minor arts", seemed unsuitable for this period, where they were, with manuscript miniatures, the most significant art forms.[60] In 2003 a reviewer noted that Ottonian manuscript illustration was a field "that is still significantly under-represented in English-language art-historical research".[61]

Notes

- ^ "Dictionary of Art Historians: Janitschek, Hubert". Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ^ a b c Suckale-Redlefsen, 524

- ^ Beckwith, 81–86; Lasko, 82; Dodwell, 123–126

- ^ a b Honour and Fleming, 277

- ^ in contrast, there are no surviving contemporary portraits of Charlemagne in manuscripts

- ^ Dodwell, 123; Imperial portraiture is a major subject in Garrison

- ^ Solothurn Zentralbibliothek Codex U1 (ex-Cathedral Treasury), folios 7v to 10r; Alexander, 89–90; Legner, Vol 2, B2, all eight pages illustrated on pp. 140-141; Dodwell, 134; the Egbert Psalter also has four pages of presentation scenes, with two each spread across a full opening.

- ^ Or so it is usually assumed, but see Suckale-Redlefsen, 98

- ^ Metz, 47–49

- ^ An area where evidence is generally thin across Europe, see Cherry, Chapter 1

- ISBN 978-0-19-820801-3.

- ^ Metz, throughout; Dodwell, 144

- ^ Suckale-Redlefsen, 98

- ^ Dodwell, 134, quoted; Beckwith, 92–93; compare the St John portraits in the Gero Codex and the Lorsch Gospels

- ^ Dodwell, 130, with his full views in: C.R. Dodwell et D. H. Turner (eds.), Reichenau reconsidered. A Re-assessment of the Place of Reichenau in Ottonian Art, 1965, Warburg Surveys, 2, of which Backhouse is a review. See Backhouse, 98 for German scholars dubious about the traditional Reichenau school. Garrison, 15, supports the traditional view.

- ^ "Illuminated manuscripts from the Ottonian period produced in the monastery of Reichenau (Lake Constance)". UNESCO. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ Or at any rate, monks depicted and named in them. Whether these would actually have been the main scribes of the text is discussed by Mayr-Harting, 229

- ^ Dodwell, 134–144; Backhouse, throughout, is rather sceptical about Trier as a major centre; Beckwith, 96–104 stresses the mobility of illuminators.

- ^ Dodwell, 141–142, 141 quoted; Lasko, 106–107

- ^ Dodwell, 134–142

- ^ Beckwith, 104, 102

- ^ Beckwith, 108–110, both quoted

- ^ Beckwith, 112

- ^ Dodwell, 151–153; Garrison, 16-18

- ^ Dodwell, 144–146

- ^ Dodwell, 153–15

- ^ Dodwell, 130–156 covers the whole period, as does Beckwith, 92–124; Legner's three volumes have catalogue entries on considerable numbers of manuscripts made in Cologne, or now located there.

- ^ Lasko, Part Two (pp. 77–142), gives a very comprehensive account. Beckwith, 138–145

- ^ Lasko, 94–95; Henderson, 15, 202–214; see Head for an analysis of the political significance of reliquaries commissioned by Egbert of Trier.

- ^ Metz, 26–30.

- ^ Lasko, 94-95; also this brooch in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Lasko, 99–109; Beckwith, 138–142

- ^ Metz, 59–60; Lasko, 98; Beckwith, 133–134.

- ^ Henderson, 15; Lasko, 96–98; Head.

- ^ Lasko, 129–131; Beckwith, 144–145.

- ^ Lasko, 64–66; Beckwith, 50, 80.

- ^ Lasko, 111–123, 119 quoted; Beckwith, 145–149

- ^ Lasko, 120-122

- ^ Lasko, 95–106; Beckwith, 138–142

- ^ Beckwith, 126–138; Lasko, 78–79, 94, 106–108, 112, 131, as well as the passages cited below

- ^ Basilewsky Situla V&A Museum

- ^ image of Milan situla

- ^ "Image of Aachen situla". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum example

- ^ Lasko, 92-3

- ^ Williamson, 26, though Lasko, 92 disagrees with this.

- ^ All except the New York situla are illustrated and discussed in Beckwith, pp. 129–130, 135–136

- ^ Beckwith, 133-136, 135-136 quoted

- ^ Lasko, 87–91; Williamson, 12; Beckwith, 126–129. On the function of the original object, Williamson favours a door, Lasko leans towards a pulpit, and Beckwith an antependium, but none seem emphatic in their preference.

- ^ Lasko, 89

- ^ Dodwell, 127–128; Beckwith, 88–92

- ^ Dodwell, 130; the Italian was "Johannes Italicus", who one scholar has identified with the Gregory Master, see Beckwith, 103

- ^ Dodwell, 128–130; Beckwith, 88–92; Backhouse, 100

- ^ Beckwith, 142; Lauer, Rolf, in Legner, III, 142 (in German)

- ^ Beckwith, 150–152 Lasko, 104

- ^ Beckwith, 132

- ^ "Crocifisso". Lombardia Beni Culturali. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ For example, Legner, Vol 2 pp. 238-240, no. E32, where a largely rubbed-down 6th-century Byzantine bookcover plaque has on the original back a Cologne relief of c. 1000 (Schnütgen Museum, Inv. B 98).

- ^ Suckale-Redlefsen, 524–525

- ^ Suckale-Redlefsen, 524; Lasko, xxii lists a number of the exhibitions up to 1972.

- ^ Review by Karen Blough of The Uta Codex: Art, Philosophy, and Reform in Eleventh-Century Germany by Adam S. Cohen, Speculum, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Jul., 2003), pp. 856-858, JSTOR

References

- Alexander, Jonathan A.G., Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work, 1992, Yale UP, ISBN 0300056893

- Backhouse, Janet, "Reichenau Illumination: Facts and Fictions", review of Reichenau Reconsidered. A Re-Assessment of the Place of Reichenau in Ottonian Art by C. R. Dodwell; D. H. Turner, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 109, No. 767 (Feb., 1967), pp. 98–100, JSTOR

- Beckwith, John. Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, 1964 (rev. 1969), ISBN 050020019X

- Calkins, Robert G.; Monuments of Medieval Art, Dutton, 1979, ISBN 0525475613

- Cherry, John, Medieval Goldsmiths, The British Museum Press, 2011 (2nd edn.), ISBN 9780714128238

- Dodwell, C.R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0300064934

- Garrison, Eliza; Ottonian Imperial Art and Portraiture. The Artistic Patronage of Otto III and Henry II, 2012, Ashgate Publishing Limited, ISBN 9780754669685, Google books

- Henderson, George. Early Medieval, 1972, rev. 1977, Penguin

- Head, Thomas. "Art and Artifice in Ottonian Trier." Gesta, Vol. 36, No. 1. (1997), pp 65–82.

- ISBN 0333371852

- ISBN 014056036X

- Legner, Anton (ed). Ornamenta Ecclesiae, Kunst und Künstler der Romanik.Catalogue of an exhibition in the Schnütgen Museum, Köln, 1985. 3 vols.

- ISBN 0521364477, 9780521364478

- Metz, Peter (trans. Ilse Schrier and Peter Gorge), The Golden Gospels of Echternach, 1957, Frederick A. Praeger, LOC 57-5327

- Suckale-Redlefsen, Gude, review of Mayr-Harting, Henry, Ottonian Book Illumination. An Historical Study, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Sep., 1993), pp. 524–527, JSTOR

- Swarzenski, Hanns. Monuments of Romanesque Art; The Art of Church Treasures in North-Western Europe, ISBN 0571105882

- Williamson, Paul. An Introduction to Medieval Ivory Carvings, 1982, ISBN 0112903770

Further reading

- Mayr-Harting, Henry, Ottonian Book Illumination. An Historical Study, 1991, 2 vols, Harvey Miller (see Suckale-Redlefsen above for review; also there is a 1999 single volume edition)